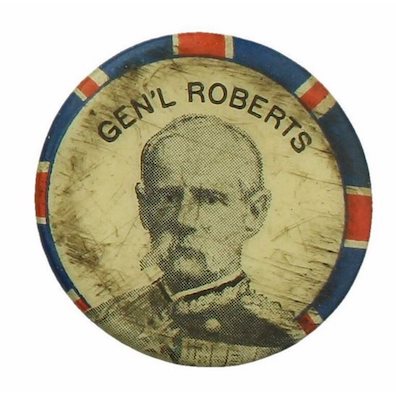

Lord Roberts commanded the British forces in South Africa for

one year, from January to December 1900. He remained very

popular after handing the reins over to Lord Kitchener, so it

makes sense that Molly would have worn "a brooch"

bearing his image in a patriotic concert. The pin with the

general's image shown here was one of many sold in the UK. The

song

that Molly sang, "the absentminded beggar," was a

collaborative effort between Rudyard Kipling (words) and Sir

Arthur Sullivan (music) designed to raise money for veterans

and their families. But "the map of it all" is obscure.

A 50-year string of commentary has interpreted these words as

referring either to Molly's face or to that Lord Roberts.

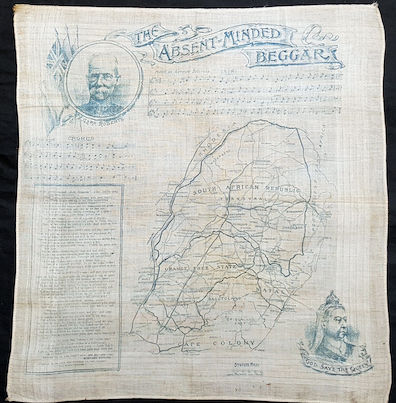

There is a much more plausible explanation: Molly once owned a

handkerchief which displayed a map of South Africa.

In a personal communication, Vincent Van Wyk has called my

attention to the existence of these handkerchiefs. For nearly

three years Britain fought a war of imperial conquest in an

unfamiliar land on the other side of the globe, and newspapers

sometimes printed maps to help their readers make geographical

sense of what they were reading. Some enterprising

manufacturers also reproduced maps of the Transvaal and the

Orange Free State on pocket handkerchiefs which people could

buy and carry about. The handkerchiefs were produced and sold

in great numbers.

It is quite plausible that Molly, after she recalls wearing a

patriotic brooch at the concert, would then recall owning one of

these patriotic handkerchiefs. Perhaps she even brought it to

the show, conspicuously displayed on her person. At similar

British concerts today, singers often wear

clothes and accessories befitting

the patriotic theme.

Penelope makes clear that

Molly has many uses for handkerchiefs and appreciates showy

ones: "how did we finish it off yes O yes I pulled him off into

my handkerchief"; "weeks and weeks I kept the handkerchief under

my pillow for the smell of him"; "and the four paltry

handkerchiefs about 6/- in all sure you cant get on in this

world without style."

This literal reading of "the map of it all" makes far better

sense than the usual, figurative interpretation. In

The

Chronicle of Leopold and Molly Bloom (1977), John Henry

Raleigh writes that Molly's phrase "is an oblique reference, I

believe, to the common saying that someone has the map of

Ireland written all over his, or her, face. This constitutes the

only reference in the book to the fact that she looks Irish as

well as Spanish-Jewish" (182). In the second edition of

Ulysses

Annotated (1988), Don Gifford repeats Raleigh's reading:

"That is, she has the map of Ireland all over her face:

colloquial for 'it's obvious that she is Irish'." Sam Slote too

(2012, 2022) affirms this sense of the phrase, but he applies it

to Lord Roberts, who was born in India to Anglo-Irish parents:

"He has the map of Ireland written all over his face: 'he is

unmistakably Irish'."

None of these commentators makes any effort to explain how

the figurative meaning might mesh with a coherent

understanding of Molly's thought and syntax. When one attempts

to do so its limitations become obvious. Why would Molly think

that she looked Irish, and why would she recall one occasion

"when" she "had" it? People normally think of others having a

certain ethnic look, not themselves, and if she thinks she had

the look of the Irish when she sang at the concert, does that

mean she has since lost it? Still another implausibility is

that, as Raleigh admits, this would be the only time in the

novel when Molly is said to appear distinctively Irish: a

Spanish Jew, she has a dark complexion that makes her look

exotic. The difficulties continue. Does Molly remember looking

Irish at the time of the concert because she thinks it somehow

advantaged her? Even among relatives of the Irishmen fighting

in the British army in South Africa, it is hard to imagine how

an Irish-looking singer on the stage would make them support

English aggression more enthusiastically.

But perhaps Raleigh supposes that the phrase connects not

with the preceding words but with what comes after: "I had

the map of it all and Poldy not Irish enough was it him

managed it this time I wouldnt put it past him."

Construed in this way, Molly is jumping from thoughts of South

Africa to the issue of being hired for concerts: Bloom has

trouble getting gigs for her because he doesn't look Irish

enough, but she had the map of it all.... This reading too is

hard to square with the fact that Molly looks exotically dark,

and with the temporal limitation of only at one time having

had the look. Even more importantly, though, her Irish

appearance seems irrelevant to landing gigs, because Molly

never once thinks of finagling concert appearances herself. In

the male-dominated concert world of turn-of-the-century Dublin

(vividly represented in "A Mother,"

and Kathleen Kearney has popped into her thoughts only seconds

before), she leaves that to people like her husband and Blazes

Boylan.

Slote avoids these problems by assuming that "I had the map

of it all" refers not to Molly but to Lord Roberts, and his

reading has one advantage: an Irish audience supporting Irish

troops might well respond favorably to a British general who

looked Irish. But in addition to the tense problem (did he

subsequently lose the look?), the grammar of the sentence

makes this reading completely absurd. The grammatical subject

is "I." How could "I had the map of it all" possibly mean that

Lord Roberts had it?