Many readers are inclined to dismiss the Homeric

correspondences as overblown distractions, or to limit Joyce's

interest in the Odyssey to his childhood encounter

with Charles Lamb's The Adventures of Ulysses. But

these readers are missing out: Joyce's novel is engaged in a

serious, though hardly straightforward, intertextual dialogue

with Homer's poem. Ulysses evokes the Odyssey

opportunistically, in ways that vary dramatically from chapter

to chapter. The echoes are quirky, unsystematic, imaginative,

and often hilarious,

but they also provoke thought about the commonalities in

ancient and modern human life. Sometimes they are so

exceedingly subtle that a century's worth of readings have

failed to appreciate their extensiveness.

In all print versions of Ulysses, the first three

chapters are preceded by a Roman numeral I, signifying that

they constitute a distinct section. A Roman II introduces

chapters 4-15, while chapters 16-18 constitute section III.

Like the first four books of Homer's poem, often called the

Telemacheia or Telemachiad, the first three chapters of Ulysses

belong to a young man (Telemachus is 20, Stephen 22)

struggling to grow into adult confidence and agency.

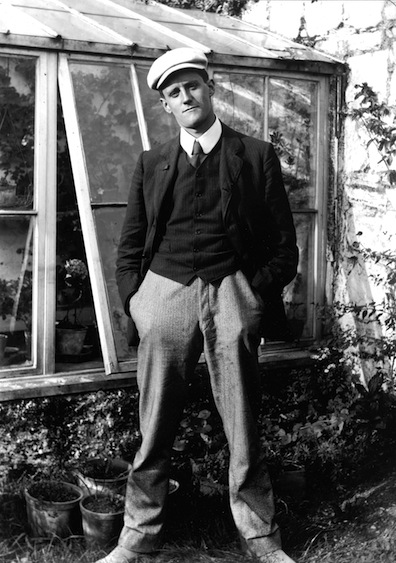

Joyce's first novel, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young

Man, was a bildungsroman, and he continued

the story of Stephen Dedalus into Ulysses. But the

mature novel shows Stephen far removed from the hopeful sense

of purpose that he felt at the end of A Portrait,

where he intended to fly by the nets flung at the soul, escape

to Paris, and forge the uncreated conscience of his race. In

this book Stephen is back in Ireland, immersed again in the

misery of his family, living with an Englishman in a tower

built by the British empire, tormented by Catholic guilt,

overshadowed by a superficially more brilliant and successful

companion, hungering for love, drinking too much, and writing

only a few impressionistic and derivative lines of verse.

Homer's poem offered a narrative analogue that could give

structure to the amorphous mass of Stephen's suffering and

striving. Joyce's Telemachiad, however, is anything but a

simple rewriting of Homer's. It is instructive to consider

what he did not include, or included only in glancing and

ironic ways. Homer's Telemachus is holding down the fort for

his father—or wishing that he could. The action is centered on

Ithaca, whose palace has been overrun by insolent young men

seeking to marry Odysseus' widow. Joyce does not really map

this story onto Stephen's, though he echoes it in many ways.

Mulligan's not paying the rent for the tower, and his

determination to drink away the fruits of Stephen's teaching

labors, are almost certainly meant to evoke the suitors'

riotous consumption of the palace's food and drink. Likewise,

Mulligan's contemptuous and contemptible treatment of his aunt's servant

(he steals a mirror from her, and jokes about seducing her)

recalls the suitors' corruption of the palace's female

servants. The old woman who comes to deliver the milk makes

Stephen think that she may be a "messenger" or a goddess in disguise,

recalling Athena's disguised embassy to Telemachus.

Least obviously but most importantly, the chapter is stuffed

with suggestions of violence. Kinch

the knife-blade, Mulligan's razor

and surgical lancet, Haines' revolver, a breakfast knife that hews and

lunges and impales, references to military barracks and expeditions and defenses, emotional "gaping wounds," thoughts

of castration, bodies "cut up

into tripes in the dissecting room," ghouls that chew on corpses: all

these details recreate the atmosphere of the palace in Ithaca,

where 108 young men assault Odysseus' patrimony, threaten the

life of his son, and invite the violent destruction that both

king and prince rain down upon them at the end of the epic.

But Joyce's first chapter contains no patrimonial homestead,

and the allusions suggesting that Stephen might need to

protect his wealth, journey in search of his father, and

violently defend his home from invaders prove to be red

herrings. He may have "paid

the rent" on one occasion, but it is clear that he is

living in Mulligan's home rather than the other way around,

and that Mulligan is supporting

him with clothes and money. Violent antipathy may lurk

just beneath the surface of the two men's relationship, but

Joyce's novel is a deeply pacifist work, and when personal

experience gave him material for Stephen to be threatened with

bodily injury in the tower, he toned it down. The old

milkwoman is no Athena; she does not come to advise Stephen,

and he scorns "to beg her favour." The tower lies close to the

water, but the hydrophobic

Stephen will not be launching a ship; it is Mulligan who

plunges into the sea at the chapter's end.

What does survive Joyce's transformations intact is Homer's

psychological portrait of a young hero in the making.

Mulligan presents himself as Stephen's friend, benefactor, and

mentor, but Stephen sees him as a disrespectful, malicious "Usurper" who would, as he says

much later in Circe, "Break my spirit." Symbolically,

this identifies Mulligan with the chief suitor, Antinous,

whose name means "anti-mind." Telemachus' need to assert adult

male independence of his mother (he, not she, is the

patriarchal heir and presumptive master of the household)

takes the form of Stephen's need to overcome the religious guilt associated

with his mother's dying. Telemachus' physical search for the

father who can help him slaughter his enemies becomes

Stephen's need to realize an idea of spiritual paternity that he

sees as synonymous with authorship. The book will steer

him toward an actual man, Leopold

Bloom, who may somehow give Stephen an image of this

spiritual ideal, but it will not join the two men in any

practical sense comparable to what happens in the Odyssey.

Rather than narrating an existential threat to a kingdom,

Joyce's chapter represents a crisis in the psychological

development of an individual. Stephen has no Ithaca to

restore, but he does need to find a home, both in the literal

sense that when he walks away at the end of the chapter he is

becoming homeless, and in the larger sense that he needs the

familial love and stability that Bloom has found. He needs an

artistic purpose, if he is not to reenact the futility of his

father's life. He needs a personal strength equal to the

forces of British colonial subjection, Catholic puritanical

self-denial, Irish political violence, and Dublin's alcoholic

fatalism. These desperate needs of a spectacularly gifted

young man make Stephen a Telemachus.

Both of Joyce's schemas indicate that Telemachus takes

place between the hours of 8 and 9 AM. The first of these

times is confirmed, near the beginning of the chapter, by the

8:15 departure of the mailboat

from Kingstown harbor, and the second at the chapter's end by

the 8:45 sounding of bells

from some Kingstown tower.