A "Ghoul" is precisely what Stephen says it is in Telemachus,

a "Chewer of corpses." In the alchemy of his imagination, his

mother has changed from a dead body to a monster that feeds on

dead bodies. She returns under this guise in Circe,

and thoughts of corpses being consumed as food connect with

many other reflections on human mortality in the novel.

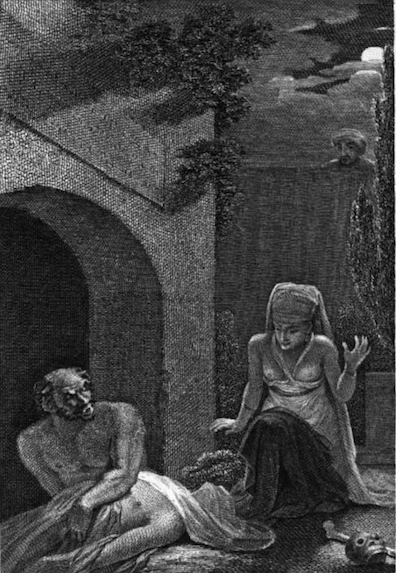

In ancient Bedouin folklore, the ghul was a wily

demonic creature that lived in desolate places, tricking human

beings who passed by and eating their flesh. It seems that

ghouls also sometimes ate bodies from graves, but this did not

become their central role until they entered western culture

through 18th century translations of One Thousand and One

Nights, a.k.a. Arabian Nights. (Joyce owned

an Italian translation of Le Mille e Una Notte when

he lived in Trieste.) One French translation in particular,

that of Antoine Galland (1704-1717), made ghouls into grave

robbers. Galland introduced into one of Sheherazade's stories

a character named Amina, who tricks a man named Sidi Nouman

into marrying her. When he notices that his bride eats nothing

but single grains of rice, he follows her out of the house one

night and sees her feasting with other ghouls in a cemetery.

Ghouls were shapeshifters in Arabic folklore, assuming the

form either of animals (often hyenas) or the human beings that

they had most recently eaten. Circe shows that Joyce

is aware of the tradition of animal-like ghouls eating the

dead and assuming their features: "The beagle

lifts his snout, showing the grey scorbutic face of Paddy

Dignam. He has gnawed all. He exhales a putrid

carcasefed breath. He grows to human size and shape. His

dachshund coat becomes a brown mortuary habit. His green eye

flashes bloodshot. Half of one ear, all the nose

and both thumbs are ghouleaten."

Reading retrospectively from this canine corpse-chewer, one

may wonder whether Bloom has glimpsed a ghoul in the "obese

grey rat" he sees crawling under a tombstone in Hades.

Bloom may not know the Arabic mythology that has captured

Stephen's imagination, but he certainly thinks of this "old

stager" as straddling the border between animal and human:

"One of those chaps would make short work of a fellow. Pick

the bones clean no matter who it was. Ordinary meat for them.

A corpse is meat gone bad. . . . Wonder does the news go

about whenever a fresh one is let down. Underground

communication. We learned that from them. Wouldn't be

surprised. Regular square feed for them."

Stephen has no doubt that his mother has entered a world of

corpse-chewing, animal-like specters. When she appears in Circe,

"her face worn and noseless," and urges him to repent his loss

of faith, he screams, "The ghoul! Hyena!"

Whether he thinks that his mother has become a monster, or

merely that one has eaten her flesh and assumed her shape,

hardly seems to matter. The lines between human and animal,

living and dead, nurturing and putrescing, have been erased,

in a vivid instance of what Julia Kristeva calls "the abject."

This Arabian thread in the book's manycolored tapestry

clearly ties into other reflections on mankind's mortal

condition: the continuity between human and animal lives

implied by "dogsbody," the

cannibalistic possibilities raised by seeing dead flesh as "potted meat," the conception

of God as a carnivore, the

transformations named by "metempsychosis."