Having mocked his roommate's "absurd name, an ancient Greek,"

the man previously known as "Buck" says ingratiatingly, "My

name is absurd too: Malachi Mulligan, two dactyls."

The resonances in this name may not be quite as numerous as

those of Stephen Dedalus,

but they evoke ancient Irish leaders (at least fleetingly), an

ancient Hebrew prophet (in a false, mocking way), and Greek

epic poetry. Later details in Telemachus fold Roman

mythology into the mix.

Noting that both names are "dactyls" confirms the typical

Irish pronunciation of the first one: MAL-uh-kee, which rhymes

rhythmically with the last name just as Oliver rhymes with

Gogarty. The dactyls also insinuate one more hint that Joyce's

novel is somehow retelling the story of the Odyssey,

because Homer's long poem was composed in dactylic hexameter:

prosodic lines of six DUH-duh-duh feet. It is possible, though

to my knowledge no one has explored the idea, that Joyce may

be inviting his readers to listen for dactylic rhythms as they

read his first chapter, just as he has asked them to hear the

Catholic Introibo being

chanted, and will ask them to hear countless musical tunes.

Malachy is a common Anglicized form of Máelachlainn, an Irish

name borne by a High King and by one of the companions of St. Patrick. But the

relative rareness of the name in Ireland, the highly unusual

"i" spelling, and Mulligan's own comments point toward a more

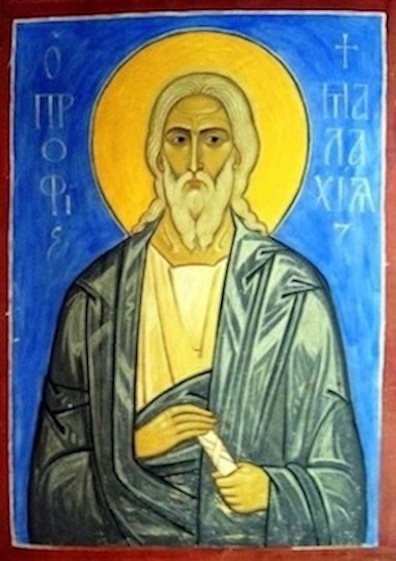

symbolic meaning. In Hebrew Malachi, the last of the twelve

"minor prophets," means “My Messenger.” Indeed, some biblical

scholars have argued that it was not a man’s proper name at

all, but a symbolic one indicating the prophet’s function as a

messenger of God. Mulligan is clearly aware of the biblical

significance of his name. In Scylla and Charybdis he

borrows a scrap of paper on which to jot down an idea for a

play: "May I? he said. The Lord has spoken to Malachi."

Mulligan's determination to “Hellenise”

Ireland arguably does make him a kind of prophet, albeit an

anti-Christian one. This assumption is supported by the way Telemachus

presents him as the bearer of evangelical "tidings": “He

swept the mirror a half circle in the air to flash the

tidings abroad in sunlight now radiant on the sea.”

In Hart and Hayman's James Joyce's Ulysses, Bernard

Benstock argues that the book makes Mulligan a kind of John

the Baptist to Stephen’s Christ, in the very limited sense

that he appears first, dramatically preparing the way for

Stephen to emerge as a character shortly after. By this logic,

Mulligan’s crudely anti-Christian message could perhaps be

characterized as a proclamation of Good News that introduces

Stephen’s similar but much more

complex and nuanced message.

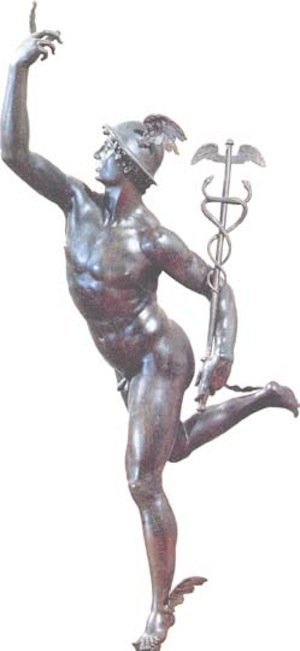

Later in the chapter Mulligan calls himself "Mercurial

Malachi" and the narrative refers to his Panama hat

as a “Mercury’s hat,” alluding to the famous

winged hat of the god Mercury. Since Mercury, the Romanized

version of the Greek Hermes, was often represented as the

gods' messenger,

carrying decrees down from Mount Olympus to human beings on

earth, this detail builds upon Mulligan’s Hebrew name of

Malachi.

By adding in references to Mercury, Joyce was apparently

paying tribute to one part of Oliver Gogarty's fanciful

personal mythology. In It Isn't This Time of Year at All:

An Unpremeditated Autobiography, Gogarty wrote, "It is

with the unruly, the formless, the growing and illogical I

love to deal. Even my gargoyles are merry and bright; my outer

darkness by terror is unthronged. My thoughts are subjected to

no rules. Behold the wings upon my helmet and my

unfettered feet. I can fly backwards and forwards in

time and space."