For a linguistically inventive people, no substitutes are

necessary to convey dislike. Creative use is made of the

ordinary name, from Mulligan’s “God, these bloody

English! Bursting with money and indigestion” to

the brilliantly funny revenge ditty placed in the mouth of an

only slightly exaggerated Citizen in Circe:

May the God above

Send down a dove

With teeth as sharp as razors

To slit the throats

Of the English dogs

That hanged our Irish leaders.

But nicknames do come in handy. In Cyclops the

Citizen speaks of "the Saxon robbers." In Telemachus

Mulligan calls Haines "A ponderous Saxon,"

and Stephen, who is energetically

resisting the Englishman's overtures of friendship,

thinks, "Horn of a bull, hoof of a horse, smile of a

Saxon." All three, according to a common saying,

are things to fear. The Scots Gaelic equivalent of Saxon, “Sassenach”

(Irish Sasanaigh), is used several times, once by

Mulligan (again, speaking of Haines to Stephen) and twice by

the Citizen ("the bloody brutal Sassenachs"). For

many centuries this term has been used for people born in

England, and not for those who have assimilated (the latter

were called gaill or foreigners in the old

annals).

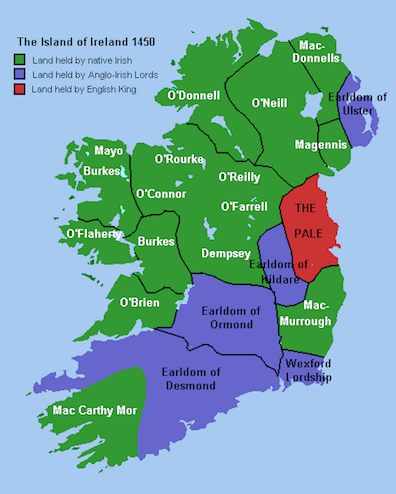

The distinction between nativized Anglo-Irish settlers and

more recent arrivals also figures in the slang word that

Stephen uses in Telemachus for Oxford students, "Palefaces."

This term supposedly originated with Native Americans

confronting their own English settlers, and the Irish

apparently use it to reverse the current of racist hatred

implicit in 18th and 19th century British stereotyping of the Irish as

dark-skinned, brutish, and subhuman, like Africans and Native

Americans.

The Citizen declaims, "We have our greater Ireland beyond

the sea. They were driven out of house and home in the black

47. Their mudcabins and their shielings by the roadside were

laid low by the batteringram and the Times rubbed

its hands and told the whitelivered Saxons there

would soon be as few Irish in Ireland as redskins in America."

If the Irish can be characterized as redskins, then

corresponding language can be applied to the people across the

Irish Sea: "Two carfuls of tourists passed slowly, their women

sitting fore, gripping the handrests. Palefaces.

Men's arms frankly round their stunted forms" (Wandering

Rocks).

But this term also plays on the fact that Dublin has always

been the city of foreign conquerors, from its founding by the Vikings to

its Georgian splendor under the British. In the late Middle

Ages, the Pale was the small part of Ireland that remained

under the direct control of the English crown after most of

the Anglo-Norman invaders forged

alliances with Gaelic chieftains and intermarried. As

the territory under the control of the English crown

contracted to the area around Dublin, and as its perimeter was

progressively ditched and fenced to hold off the natives, it

came to be known metonymically by the Latin name for a stake (palus)

driven into the ground to support a fence. Those outside the fence were

“beyond the pale.” Those inside it—essentially, the

inhabitants of greater Dublin—were “Palemen.”

Perhaps the most interesting of these slang epithets is

“stranger,” or “stranger in the house.” Stephen uses it when

thinking of Haines, Deasy of the Anglo-Norman invaders in the

12th century, and Stephen again in Scylla and Charybdis

when he alludes to the Countess

Kathleen bemoaning “her four beautiful green

fields, the stranger in her house” (i.e., the four

provinces of Ireland, and the English invaders). Old Gummy

Granny, Circe’s hallucinatory version of the

mythical Poor Old Woman,

spits, “Strangers in my house, bad manners to them!”

In light of the novel's frequent use of this Irish expression

of resentment, it is interesting that Bloom is called a

stranger several times. The antisemitism

expressed by many of Dublin’s citizens prepares the reader for

this nomination. At the end of Nestor, Mr Deasy

jokes that Ireland has never persecuted the Jews “Because she

never let them in.” In Cyclops, the xenophobic

Citizen extends his dislike of the British to the Jewish-Irish

Bloom. "We want no more strangers in our house,"

he says. Oxen of the Sun appears to

perpetuate this mentality when Mulligan and the other young

men in the maternity hospital think of Bloom several times as

“the stranger.” Perhaps they are simply not

used to seeing him in the hospital, but their use of the term

may very well be xenophobic.

All three of the book's protagonists could be called

strangers: the partly Jewish Bloom, the exotically

Mediterranean Molly, and the young man with an "absurd name,

an ancient Greek."

Joyce's dislike of British rule

was tempered by his awareness that Ireland has been shaped by

repeated waves of conquest and assimilation. In Finnegans

Wake he created another male protagonist who is

regarded suspiciously as an outsider. Mr. Porter, the

(possible) daytime instantiation of HCE, seems to be a

Protestant, just as Bloom is Jewish, and HCE is associated

repeatedly with the seafaring conquests of Danes, Norwegians,

Jutes, Normans, Englishmen, and other Germanic invaders. His

recurrent compulsion to defend his existence seems connected

to Ireland's aggressive suspicion of outsiders: "So this is

Dyoublong? Hush! Caution! Echoland!"

In The Irish Ulysses (U. California Press, 1994),

Maria Tymoczko argues that the ancient Irish text called The

Book of Invasions "helps to explain why the central

characters in Ulysses are all outsiders though they

stand as universalized representations of Dubliners, for the

invasion theory of Irish history in Lebor Gabála is

predicated on the notion that there are no aboriginal

inhabitants of the island. In this scheme, everyone is an

outsider, descended as it were from immigrants. From the

perspective of Irish pseudohistory, the cultural alienation of

Stephen, Bloom, and Molly mirrors the heritage of all the

island's inhabitants as descendants of invaders" (35). Greek,

Jew, and Spaniard, by this reading, stand in for Nemedians,

Formorians, Fir Bolg, Tuatha de Danann, Goidels-Milesians,

Dane-Vikings, Anglo-Normans, English, and Scots.