Mulligan's "great searching eyes" are the first of many that

one becomes aware of in reading Ulysses. In this novel

characters' eyes frequently convey information about their

minds, and none more so than Mulligan's.

In Telemachus, Mulligan has "great searching eyes,"

"mobile eyes." Stephen's decision to disclose his grievance

against Mulligan stirs "silver points of anxiety in his eyes."

When he is clowning, his eyes blink "pleasantly"; they lose

all evidence of "shrewd sense," "blinking with mad gaiety."

But Stephen sees the shrewd sense, and he discerns Mulligan's

intention to claim the key:

"He will ask for it. That was in his eyes." He sees things in

Haines' eyes as well: their "wondering unsteady" quality when

he begins declaiming Irish

to the old milkwoman; the "firm and prudent" quality they

display as the Englishman looks out on the sea, his nation's dominion;

the fact that, despite Stephen's wish to dislike the stranger, "the cold

gaze which had measured him was not all unkind." (In Nestor,

Stephen recalls that Haines' eyes were "unhating.")

§ Some

textual controversy attends the first of these glimpses of a

character's eyes. Gabler’s edition replaces “great

searching eyes” with “grey searching eyes.” It is hard

to prefer this change on aesthetic grounds. Losing the

suggestion of intellectual spaciousness, "grey" gains in

return only a possible symbolic suggestion that, as Gifford

notes, Buck Mulligan may be similar to Athena, because she is

called the “grey-eyed goddess” throughout the Odyssey.

But this correspondence is built on shaky ground. The word

sometimes translated as “grey-eyed” in English versions of the

Odyssey, glaukopis, more properly means

“with gleaming eyes.” Even if one supposes that Joyce intended

a comparison between Mulligan and Athena, it is hard to make

sense of it. Why would he cast Mulligan both as Stephen's Antinous-like antagonist and as

his beneficent protector?

Gabler's emendation appears not only pointless but also

highly arbitrary if one takes account of the fact that

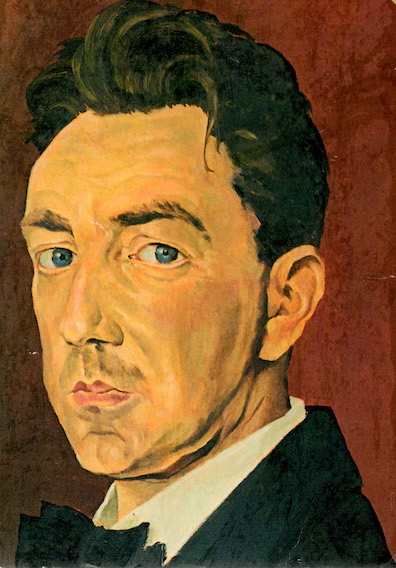

Mulligan's model, Oliver St

John Gogarty, had strikingly blue eyes. Here is

Gogarty's biographer Ulick O'Connor: "The eyes are striking,

vivid blue, so deep in colour that his daughter actually

remembers their being a shade of violet at times. His hair is

brown, but sometimes streaked with gold from the bleaching of

the sun, and inclinced to stand upright when brushed sideways"

(20). Joyce captured the mix of hair colors in his fifth

paragraph by describing Mulligan's hair as "grained and hued

like pale oak." Why would he have chosen to change the vivid

blue eyes to a duller hue? In fact, he did not. Mulligan's

eyes are described later in Telemachus as "smokeblue"—greyish,

perhaps, but hardly grey. This is one of a distressingly large

number of instances in which Gabler's efforts to produce a

"corrected text" introduced new and totally unnecessary

errors.