Having already mocked the Irish Literary Revival on the tower's

parapet ("A new art colour for our Irish poets: snotgreen. You

can almost taste it, can't you?"), Mulligan again swivels his

wit that way as he serves breakfast in the room below:

"— That's folk, he said very earnestly, for your book,

Haines. Five lines of text and ten pages of notes about the

folk and the fishgods of Dundrum. Printed by the weird sisters

in the year of the big wind." His target here is the

cultivation of Irish “folk” identity: ancient legends, myths,

customs, and spiritual beliefs that were being studied and

imitated by scholars and writers from the 1880s onward. His

sarcasm is directed particularly at the greatest of the

Revival writers, William Butler Yeats, from whose Fergus

song he has just been quoting.

Thornton notes that "five lines of text and ten pages

of notes" seems to refer to "the work of the

antiquarians who were editing, explaining, and annotating

early Irish literature and folklore at this time." Gifford

says of the project, “At times this interest ran to

hairsplitting scholarship and at times to gross

sentimentality.” For Haines's benefit, Mulligan adopts the

persona of a hairsplitting pedant, and proceeds to demean the

seriousness of the scholarly enterprise by citing all sorts of

inauthentic arcane beliefs. A central figure in his mockery is

Yeats, who joined the ranks of the scholars when he edited a

collection titled Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish

Peasantry in 1888. Yeats' poems in the 1880s and 1890s

show how extensively and beautifully these myths could shape a

vision of Irish life, and at the same time how readily they

could encourage escapism, freefloating sentiment, and vague

substitutes for thought.

“The fishgods of Dundrum” ridicules Yeats'

obsession. Gifford notes that fish gods “are associated with

the Formorians, gloomy giants of the sea, one of the legendary

peoples of prehistoric Ireland.” But Dundrum makes no sense in

connection with the Fomorians. One Dundrum, north of Dublin,

was the place “where ancient Irish tribes held a folk version

of Olympic games.” Another, south of Dublin, was the site of

an insane asylum and of a village where Yeats’ sister

Elizabeth established the Dun Emer press in 1903 to publish

his “new works and works by other living Irish authors in

limited editions on handmade paper.” Her sister Lily became

involved with the Dun Emer Guild, “which produced handwoven

embroideries and tapestries.” Readers can now discern the

context for Mulligan's earlier reference to "A new art

colour" for the covers of poetry books.

So a piece of authentic mythology (fishgods) is mixed up with

some unrelated ancient customs, and both are attached to the

Yeats family enterprise of reviving Irish art, with the

implication that all these cultural enterprises, and all three

Yeats siblings, belong in a lunatic asylum. At the end of

Oxen of the Sun, Mulligan can be heard continuing to

mock the Yeats sisters' publishing enterprise, now calling it

the "Druiddrum press." The "Ayes

have it," he proclaims: the bawdy ditty he is

chanting, or possibly Stephen's parody of the Sermon on the

Mount, is "To be printed and bound at the

Druiddrum press by two designing females. Calf covers of

pissedon green. Last word in art shades. Most

beautiful book come out of Ireland my time." The last sentence

repeats a

different attack on Yeats that Mulligan has made in Scylla

and Charybdis, mocking his praise of Lady Gregory,

another prominent writer of the Literary Revival.

“Printed by the weird sisters in the year of the big

wind” establishes another chain of bizarre and

wildly funny associations. The “weird sisters” have

nothing to do with Irish mythology. They appear in

Shakespeare’s Macbeth as Scottish witches whose name

may owe something to the Old English concept of wyrd,

fate. But after the glancing allusion to two sisters involved

in the publishing business it seems that Yeats’s sisters are a

bit weird. And indeed these sisters have used the phrase "the

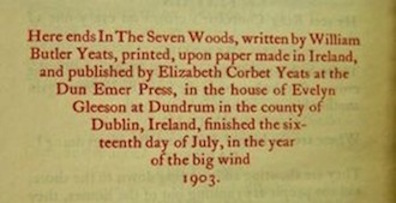

big wind." The Dun Emer edition of Yeats’s In

the Seven Woods announces that the book was completed

“the sixteenth day of July in the year of the big wind, 1903.”

This phrase usually refers to 1839, which saw a terrible

windstorm that destroyed hundreds of houses. There was another

formidable tempest in 1903, but there is nothing ancient or

mythological about it. In Aeolus it is referred to

as "that cyclone of last year," and Oxen of the

Sun mentions "the big wind of last February a

year that did havoc the land so pitifully."

In his final sally, Mulligan turns from slandering the Yeats

family and riffing on mythology to mocking scholarly pedantry.

Addressing Stephen as if he were a professorial colleague, and

imitating academic affectation “in a fine puzzled voice,

lifting his brows,” he asks for assistance with a

bibliographic citation: "is mother Grogan's tea and

water pot spoken of in the Mabinogion or is it in the

Upanishads?" The question is as absurd as Feste

asking “For what says Quinapalus?” in Shakespeare’s Twelfth

Night. Mother Grogan is a character in a silly

contemporary Irish song rather than a figure of ancient

folklore. The medieval Mabinogion contains many

ancient Celtic legends, but it is Welsh rather than Irish. And

the Upanishads are ancient Vedic texts of Hindu spirituality

and philosophy—of great interest to Theosophists, but

otherwise completely unconnected to Ireland. Stephen,

“gravely” participating in the scholarly charade, ends the

mockery with his own very funny reply to Mulligan’s

which-is-it question: "I doubt it."

Even here, though, there is a Yeats connection: in praising

Lady Gregory's Cuchulain of Muirthemne: The Story of the

Men of the Red Branch of Ulster (1902) as the best to

come out of Ireland in his time, Yeats compared

the book to the epic tales in the Mabinogion.

Some readers have also speculated about how the Anglo-Irish

Haines may be implicated in Mulligan's mockery. On

ulyssesseen.com, Andrew Levitas argues that in referring to

the Mabinogion and the Upanishads Mulligan intends "to

skewer Haines’ attitude toward Ireland and things Irish.

Haines is collecting 'exotic' Irish sayings and other folk

esoterica, in the same way Bartok, Dvorak and Smetana

collected ethnic folk tunes from the backwaters of the

Austro-Hungarian Empire, as modernity began to overtake these

regions." Since Wales is "another Celtic nation incorporated

into Great Britain," and India is "Britain’s leading colony,"

Mulligan may be mocking the Englishman's project of cultural

appropriation.