Pantomime originated in the ancient world. The Greek name

originally indicated that the actor or actors “imitate all,"

and quite a bit is known about a low Roman art form of that

name, which featured a male dancer telling mythical or

legendary stories. But the modern form can more plausibly be

traced back to the Mummers Play

of medieval England and the Commedia dell’arte of

Renaissance Italy. Theaters in Restoration and 18th century

England adapted elements of the Commedia, and in

the early years of Queen Victoria's reign a new kind of

popular but sophisticated show took shape, based on children’s

fairy tales that everyone in the audience could be assumed to

know, including northern European ones like Cinderella, Mother

Goose, Dick Whittington, and Humpty Dumpty, and also exotic

foreign stories like Aladdin, Ali Baba, Sinbad, and Robinson

Crusoe. These entertainments, which spread to all the farflung

parts of the empire, were, like mummers' plays, usually

performed in the Christmas and New Year season.

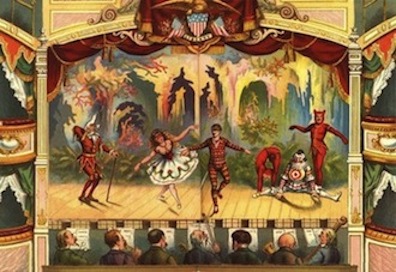

Using one fairy tale as a broad canvas, the shows featured

many diverse kinds of free, improvisatory entertainment:

dances, well-known popular songs set to new lyrics,

cross-dressing roles, slapstick comedy, evil villains and good

fairies, clowns, jugglers, acrobats, topical allusions and

jokes, sexual innuendo, appearances by local guest stars, and

frequent audience participation: watchers were expected to

shout out suggestions to the performers and sing along with

well-known songs. The story line ran very loosely through all

these incidentals, and tended to be wrapped up quickly and

unrealistically.

The "Turko the terrible" that Stephen

thinks of in Telemachus, and Bloom in Calypso,

had been performed in Dublin for decades. Thornton notes

that William Brough’s pantomime Turko the Terrible; or,

The Fairy Roses, first performed in 1868 at London's

Gaiety Theatre, was adapted by the Irish author Edwin Hamilton

for performance in Dublin's Gaiety Theatre, first in 1873 and

then many times more in the remainder of the 19th century.

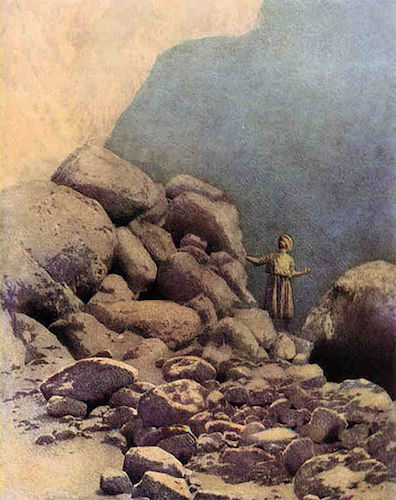

Bloom thinks of Turko as he imagines himself wandering through

the streets of a Middle Eastern city. In Circe,

Molly’s father, Major Brian Tweedy, acquires this exotic

aspect.

"Old Royce," whom Stephen imagines playing

the role, was Edward William Royce, an English comic actor who

often performed parts in pantomimes. His presence in Stephen's

thoughts may owe to the fact that he appeared as Turko in

performances of an unrelated pantomime that Joyce could well

have attended. Robert Martin Adams observes that in the Sinbad

the Sailor of 1892-93, "Mr. E. W. Royce was one of the

featured performers; and his appearance was billed as the

first since his return from Australia. He took the part of

Turko the Terrible, not that this part was an invariable

feature of Sinbad the Sailor...but because, as an old

Dublin favorite, he had to be worked in somehow" (Surface

and Symbol 77-78).

In Ithaca Bloom thinks of “the grand

annual Christmas pantomime Sinbad the Sailor,”

performed in December 1892 and January 1893 at the Gaiety

Theatre. As the poster reproduced here shows, he correctly

identifies the theater manager as "Michael Gunn, lessee of

the Gaiety Theatre," but he is quite mistaken that the

show was "written by Greenleaf Whittier." An obscure

author named Greenleaf Withers penned the script, not the

famous (and highminded) 19th century American poet John

Greenleaf Whittier. Adams points out this mistake, as well as

the fact that Joyce has combined two of the actresses, Kate

Neverist and Nellie Bouverie, into "Nelly Bouverist,

principal girl."

Adams also reflects on the many pieces of information that

Joyce learned about Sinbad (some included in the

account in Ithaca, and many others omitted) from an

advertisement touting the show that ran on p. 4 of the Freeman's Journal on 24

and 26 December 1892. Among the details in the ad was an

announcement of a spectacular episode in scene 6:

GRAND BALLET

of

DIAMONDS

and

SERPENTINE DANCE

Bloom recalls wanting to write "a topical song

(music by R. G. Johnston)" to insert into "the sixth

scene, the valley of diamonds, of the second edition (30

January 1893)" of the pantomime. The changing of

"ballet" into "valley" in all editions of the novel (Gabler's

included) might be supposed to represent a failure of memory

on Joyce's part or Bloom's. But "the valley of diamonds,"

in the second of Sinbad's seven voyages, is a place where

diamonds lie scattered about on the ground. Merchants harvest

them by throwing out pieces of meat that are snatched up by

giant birds called rocs, then driving the birds away from

their nests and collecting the diamonds that have stuck to the

meat. As he drops off to sleep Bloom is still thinking of Sinbad, and

of rocs.