In Telemachus and again in Scylla and

Charybdis Mulligan calls Stephen "A lovely mummer!...

Kinch, the loveliest mummer of them all!"; "O, you peerless

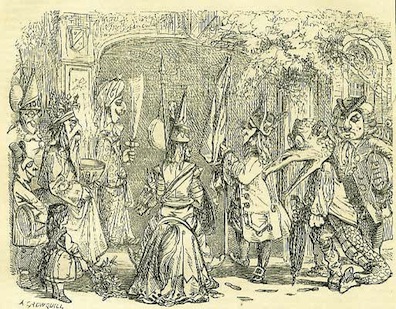

mummer!" Mummers were (and, in some places, still are)

impromptu comic actors who performed in the streets, in inns

and public houses, and in visits to private houses (just as

carolers and trick-or-treaters do). Their performances

typically revolved around a story of death and resurrection:

the young hero is killed, and a quack doctor revives him.

Mumming derived from secular folk plays in the Middle Ages,

related to other carnival rites like morris dances but distinct from

church-sponsored theatrical events like mystery plays. Begging

was often involved: performers would visit great houses,

usually just before or just after Christmas, expecting to

receive handouts. Masking too played a part: cognates of

“mummer” in various medieval languages (Middle English, Middle

Dutch, Early New High German, Old French) carried the

principal meaning of wearing a mask or disguise. These comic

performances were still going strong in the British Isles in

the late 19th and early 20th centuries, though the tradition

has weakened since then.

Mulligan feels an affinity for these impromptu clowners. In

Scylla and Charybdis he declares that "I have

conceived a play for the mummers," and launches

into the very funny title page of a lewd skit. The spirit of

mummery informs his comic performances in Telemachus

(the transubstantiation

of soap, the melting of

candles, the water-making of Mother Grogan and Mary Ann, the ballad of the Joking Jesus, the disquisition on Celtic antiquities)

and Oxen of the Sun (the fertilizing farm). It is

not so clear, however, why he would call Stephen a lovely

mummer. For most of the book Stephen is painfully serious.

Even the wry telegram that makes Mulligan call him "peerless"

shows little of Mulligan's genius for comic improvisation. The

flashes of humor that periodically break through the dark

clouds of Stephen's rumination are typically wry and

ironic—hardly the stuff to please a crowd.

With the onset of drunkenness

in Oxen of the Sun, however, Stephen becomes

funnier, and he taps the same comic veins that Mulligan

enjoys: blasphemous mockery of religion, and crude

celebrations of carnality. His wild ramblings in this episode

are quite cerebral (his audience is learned), and we hear them

filtered through the medium of the episode’s ornate prose

narration. But Circe gives us something closer to

his words as he performs a little skit for Lynch and the

whores. After Bella objects to some lewd jokes, Lynch says,

“Let him alone. He’s back from Paris,” and Zoe, “O go

on! Give us some parleyvoo.” “Stephen claps hat on

head and leaps over to the fireplace, where he stands with

shrugged shoulders, finny hands outspread, a painted smile

on his face,” and performs a very funny imitation of a

Parisian hawker enticing passersby to enter an establishment

and see a sex show.

This lewd performance may not correspond to any dialogue ever

heard in a holiday play, but it does display Stephen in a fit

of brilliant comic improvisation that might justify Mulligan’s

judgment that he is “a lovely mummer!” And,

intriguingly, Circe reaches its climax in a series

of events that reproduce the central action of many mummers’

plays: the death and resurrection of the hero. Stephen is

knocked flat on his back by a British soldier. As action

swirls over his prostrate body, the funeral home worker Corny

Kelleher, “weepers round his hat, a death wreath in his

hand, appears among the bystanders” and offers to carry

Stephen on the cart in which he has just ferried two lechers

to Nighttown. It appears finally that his assistance will be

unnecessary: “Ah, well, he’ll get over it. No bones

broken. Well, I’ll shove along. (He laughs) I’ve a

rendezvous in the morning. Burying the dead. Safe home!"

Stephen, then, escapes the honor of being ferried to Glasnevin

cemetery by Corny, as Paddy Dignam was on the morning of June

16.

In an unpublished doctoral dissertation (Purdue University,

1989) titled

James Joyce: “The loveliest mummer of them

all,” Frances Jeanette Fitch pursues a different

interpretation, suggesting that Stephen’s mumming is displayed

in his Shakespeare talk in

Scylla and Charybdis. She

also connects the tradition to Stephen’s name, observing that

December 26, the most common day for mummery in Ireland, is not

called Boxing Day in that country but... St. Stephen’s Day.