Mulligan's poem in Telemachus strives to offend

Catholic sensibilities twice in one line: "My mother's a

jew, my father's a bird." Christians have long thought

of Jesus and his blessed mother as something other than Jews,

and when they put doves in Annunciation scenes they do not

think of the Holy Spirit literally as a randy bird. The second

joke returns in Proteus, with the dove demoted to a

mere "pigeon," when Stephen recalls a work called "La

Vie de Jésus by M. Léo Taxil."

In Nestor Mr. Deasy repeats the old canard that by

killing Jesus the Jews "sinned

against the light," ignoring the fact that Jesus was

himself a Jew. In Eumaeus Bloom recalls how he

enraged the Citizen by saying "your God was a jew," reflecting

that "mostly they appeared to imagine he came from

Carrick-on-Shannon or somewhere about in the county Sligo."

In the context of such ethnocentrism, Mulligan's "My

mother's a jew," while factually

unremarkable, is effectively insulting.

Saying "my father's a bird" goes

further into the realm of blasphemy, by reading a traditional

symbol of the Holy Spirit literally and imagining avian-human

intercourse. The gospel of Luke recounts the angel

Gabriel's visit to Mary in what became known as The

Annunciation. The angel says that the Holy Spirit "will come

upon you" (!), and that Mary will become pregnant with the Son

of God. In later pictorial representations, the Holy Spirit

often took the form of a dove. So, in Mulligan's mind, a

testosterone-maddened pigeon came upon Mary and inseminated

her.

Mulligan's image fills Stephen's imagination as he walks

toward the Pigeonhouse in

Proteus. He recalls a very brief exchange from a

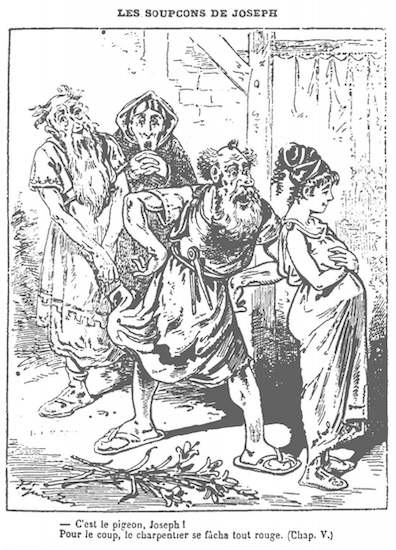

ponderously long (389 pp.) work titled La vie de Jésus,

published in 1884. In that work, writing under the pen name

Léo Taxil, Gabriel Jogand-Pages tells how Mary's cuckolded

husband, Joseph, demands, "Qui vous a mis dans

cette fichue position?" ("Who has put you in

this rotten position?"). Mary's orthodox account of the

paternity is marred by a choice of words very similar to

Mulligan's "bird": "C'est le pigeon, Joseph"

("It was the pigeon, Joseph"). This blasphemy enraged the

Vatican, and Jogand-Pages was forced to apologize to the papal

nuncio and travel to Rome for what Gifford calls "a

well-publicized papal absolution" (53).

In Oxen of the Sun, Stephen is still thinking of

the passage: "parceque M. Léo Taxil nous a dit que

qui l'avait mise dans cette fichue position c'était le

sacré pigeon" ("because M. Leo Taxil tells

us that it was the blasted pigeon that put her in this rotten

position"). In a personal communication, Ole Bønnerup tells me

that when placed before a noun, rather than after it, the

adjective sacré changes its meaning from "sacred" or

"blessed" to something like "bloody" or "goddamn," so Stephen

is adding his own linguistic irreverence to Taxil's.

The thought that a pigeon sired Jesus sends Stephen's mind on

to a young man he knew in Paris named Patrice Egan. It was

Patrice who recommended La vie de Jésus to Stephen.

But Patrice has more than an incidental connection to the

conceit. Since his father Kevin Egan is a "wild goose," he too

can truthfully say, "My father's a bird." As

in Stephen's conceit about

algebra, where morris dances and Moorish turbans combine

with the Moorish art of mathematics, the pieces interlock

wonderfully.