Homer shows Telemachus taking action first by calling an

assembly of the men of Ithaca to condemn the suitors'

depradations, and, when that fails, by voyaging to Pylos and

Sparta on the Greek mainland to see what Nestor and Menelaus

may know of his father. Nestor receives him hospitably and

tells him the relevant story of what happened to Agamemnon

when he returned home, but he has no information about

Odysseus. Stephen's case is worse: Deasy afflicts him with

unsought and aggressive advice, and Stephen actively resists

the headmaster's assumption of intellectual authority.

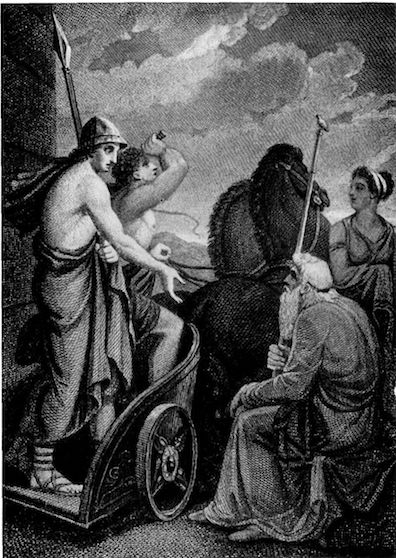

Joyce's narrative clearly associates Deasy with Nestor. The

portraits of "vanished horses" on the walls

of his study—champion racehorses from the 1860s, 70s, and

80s—echo Nestor's reputation as "the prince of

charioteers," a reputation that is illustrated when

Nestor sends Telemachus and his son Peisistratus off to Sparta

behind a pair of "thoroughbreds, a racing team."

The concern for cattle that Deasy shows in writing his letter

about foot-and-mouth disease reflects the monumental sacrifice

of bulls that greets Telemachus when he arrives at Pylos, as

well as the sacrifice of a prize heifer to Athena the next

day. There are many additional

echoes, but Joyce's episode engages with Homer's most

crucially on the theme of a young man seeking advice from an

old one. Athena urges Telemachus to learn from Nestor:

"Go to old Nestor, master charioteer,

so we may broach the storehouse of his mind.

Ask him with courtesy, and in his wisdom

he will tell you history and no lies."

But clear-headed Telémakhos replied:

"Mentor, how can I do it, how approach him?

I have no practice in elaborate speeches, and

for a young man to interrogate an old man

Seems disrespectful—"

Despite this veneration for the old man's wisdom, Nestor does

not have any actionable information. His knowledge of

Odysseus' whereabouts ends with the departure from Troy. Joyce

took this deflation of patriarchal wisdom considerably

further. Mr. Deasy tells Stephen (who has not asked) a

boatload of "history," including the United

Irishmen rebellion of the 1790s, the Act of Union in 1800-1,

Daniel O'Connell's parliamentary reform movements in the first

half of the 19th century, the famine of the 1840s, and the

fenian conspiracy of the 1860s. But his Protestant unionist perspective on these

events is one that Stephen can hardly embrace. And his

aggressively partisan position is undermined by many, many "lies."

For Stephen, Deasy's biased memories are not simply

inaccurate. They are depressingly representative of history in

general, which is written by the winners and effaces the

losers. In Deasy's complacent unionist view, "All human

history moves towards one great goal, the manifestation of

God." In Stephen's subjected condition, history is "a

nightmare from which I am trying to awake." Joyce named

history as the "art" of Nestor in both of his schemas. It is an art whose

practice depends hugely on one's subject position.

According to the Linati schema, the episode takes place from

9 to 10 AM. According to Gilbert's, the time is 10-11 AM.

Neither of these on-the-hour times fits precisely with the

details that can be found in the text or inferred from it. The

chapter begins in the middle of a lesson, so the time must be

later than 9:00, since Telemachus ended at 8:45

and it must have taken Stephen at least 15 minutes to walk the

mile from the Sandycove tower to Dalkey Avenue. It is

impossible to say exactly how long the lessons have been going

on, but not very much textual time elapses before the boys

remind Stephen that they have "Hockey at ten, sir."

Estimating backward from this hour to account for the history

and literature lessons that we hear narrated, for Stephen's

riddle, and for his tutoring of Sargent while the boys dress

for the match and Deasy sorts the teams, one may reckon that

the action of the chapter begins somewhere around 9:30.

The conversation between Stephen and Deasy in the

headmaster's office must begin at about the same time as the

boys' recess, 10:00, and it occupies slightly more than half

the chapter. An estimate of 10:30 would fit with the time

frame of Lotus Eaters,

preserving the temporal parallels that Joyce evidently

intended between Stephen's first three chapters and Bloom's.

It clashes, however, with the time of 10:00 that Clive Hart

infers from his account of how Stephen travels from Dalkey to

Sandymount Strand between Nestor and Proteus (James

Joyce's Dublin, 27-32). Persuasive as Hart's account of

Stephen's movements is, it seems impossible that his

conversation with Deasy could conclude by 10:00.