In his list of creditors in Nestor Stephen recalls

that he owes "Curran" a quite large sum: "ten guineas."

Constantine Curran, "Con" or "Conn" to his friends, was a

friend to Joyce from their university days until the end of

Joyce's life. Of the ten college-age acquaintances in the

list, he is one of seven represented under their own names.

The other three––Mulligan, McCann, and Temple––are fictive

names for actual acquaintances.

Curran was born in Dublin on 30 January 1883, nearly one year

later than Joyce. The two met at University College, Dublin in

1899. Curran received a B.A. degree from the institution in

1902 and an M.A. in 1906. He studied law and was admitted to

the bar, but he never practiced. Instead he took a job in the

Accountant General's office of the Four Courts, and in 1946 he

became Registrar of the Supreme Court. He also studied

Dublin's architecture, particularly its plasterwork, and

published three books on those topics in 1945, 1953, and 1967.

He married actress, costume designer, and political activist

Helen Laird in 1913, and the two held celebrated cultural

salons on Wednesday afternoons at their home on Garville

Avenue.

In 1904 Curran was living at his parents' house just off the

North Circular Road, near the Christian Brothers

school on North Richmond Street.

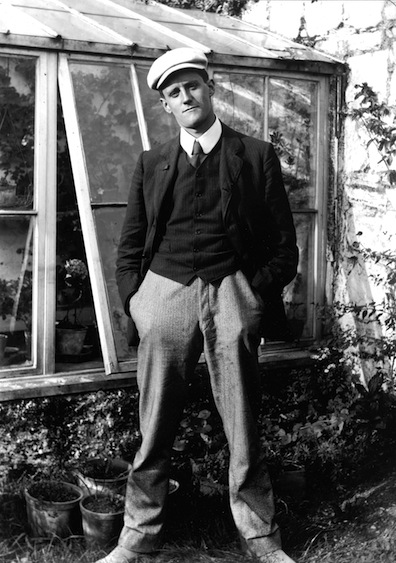

It was in the garden of that house that he took a famous

photograph of Joyce standing with his hands in his pants

pockets, a yachting cap on his head. Asked what he was

thinking when Curran posed him, Joyce replied, "I was

wondering would he lend me five shillings." Curran did lend

him money on many occasions.

Ellmann writes of this "goodhearted" man that Joyce "in the

course of his lifetime was to owe Curran a great many

kindnesses" (63). In 1904, "Thanks to C. P. Curran, he was

able to pay something down at Piggott's and had a grand piano

delivered" (151). In the same year "Curran made him several

small loans with uncomplaining generosity" (162). After

calling The Holy Office "an unholy thing," Curran

"mollified him with a little money" (165). In 1905 Joyce wrote

to Stanislaus about the birth of his son "and asked him to

borrow a pound from Curran to help pay expenses" (204). In

1912, when he was desperately urging George Roberts to publish

Dubliners after three years of delays, "Curran proved

friendly and willing to speak to Roberts on his behalf" (329).

Gordon Bowker, in his "New Biography," glances at Curran's

many loans to Joyce, as in the following sentence: "Now that

the 'harshness of his situation' was revealed, Joyce invited

himself to Curran's office (he worked for the Accountant

General) hinting that he was 'in a bloody hole', and ready as

ever to take a loan if offered" (124). But he devotes more

attention to the kindnesses that Curran did Joyce later in

life, including the assistance that he provided to Lucia. When

Joyce died, Curran published an obituary in the Irish

Times showing that his devotion proceeded not only from

Christian kindness but also from a clearheaded assessment of

Joyce's genius: "His later life belongs to world literature,

where his influence has been as widespread, as profound and as

disruptive as that of Picasso in painting. He was as great a

master of English prose as Yeats was of English verse—that is

to say, he was one of the two greatest figures in contemporary

English literature" (535).

In 1968 this goodnatured and intelligent man published a

memoir of his lifelong friend titled James Joyce

Remembered. A new edition of the book, with scholarly

apparatus and many illustrations, is being released this year

by the University College Dublin Press and the University of

Chicago Press.