As if in response to Stephen's salvo about God being a shout in the street,

which cannot possibly make any sense to him, Deasy's

argumentative tirade trails off into irrelevancy and sheer

unintelligibility. He scores a glancing ad hominem

blow: "I am happier than you are." But then he veers into

thoughts of sexual sin: "We have committed many errors and

many sins. A woman brought sin into the world. For a

woman who was no better than she should be, Helen, the runaway

wife of Menelaus, ten years the Greeks made war on Troy. A

faithless wife first brought the strangers to our shore here,

MacMurrough's wife and her leman, O'Rourke, prince of Breffni.

A woman too brought Parnell low." What is one to make of all

the misogyny? One possibility is that there has been adultery

in Deasy's marital past.

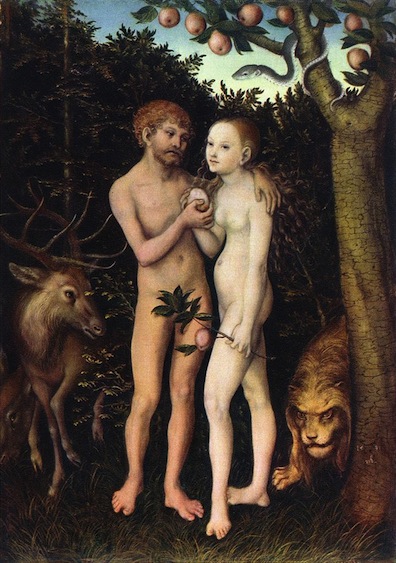

In addition to Eve, who tempted Adam to transgress God's

command and thereby "brought sin into the world,"

Deasy mentions "Helen, the runaway wife of Menelaus,"

whose adulterous elopement with Paris occasioned the long and

catastrophic Trojan War. Stuart Gilbert argues that this

reference to ancient Greek history makes Deasy like Nestor in

the Odyssey, since Nestor tells Telemachus about the

adulterous Clytemnestra's murderous reception of her husband.

Two more references to adultery follow. Another "faithless

wife" who caused disaster was Devorgilla, the

spouse of "O'Rourke, prince of Breffni,"

whose adulterous elopement with Diarmait "MacMurrough,"

the king of Leinster, contributed to MacMurrough's deposition

and subsequent conspiracy with the English king Henry II to

launch the first Anglo-Saxon invasion of Ireland, and thus "first

brought the strangers to

our shores here." Thornton observes that Deasy has

managed to switch the two men, turning MacMurrough into the

husband and O'Rourke into the lover: Deasy gets his facts

wrong once more.

But this domestic history seems to be a staple of Irish

political mythology. In Cyclops, the Citizen makes

the same claim about how the "strangers" came to Ireland: "Our

own fault. We let them come in. We brought them in. The

adulteress and her paramour brought the Saxon robbers here.

. . . A dishonoured wife, . . . that's what's the cause of

all our misfortunes." A third faithless wife,

Katherine O'Shea, "brought Parnell low" when

their adulterous affair was discovered.

Deasy's list of female sinners makes an odd lead-in to his

assertion that "we" have committed "Many errors, many

failures but not the one sin," which seems to

reprise his claim that the Jews "sinned

against the light." And it does not contribute

intelligibly to the exchanges he has been having with Stephen

about Jews, Catholics, Protestants, Tories, and Fenians.

It may, however, make some sense in terms of Deasy's personal

life. In Aeolus Myles Crawford tells Stephen that he

knows Deasy, "and I knew his wife too. The bloodiest

old tartar God ever made. By Jesus, she had the foot and mouth disease

and no mistake! The night she threw the soup in the waiter's

face in the Star and Garter. Oho!" After recalling Deasy's

misogynistic catalogue, Stephen asks the editor whether Deasy

is a widower. Crawford replies, "Ay, a grass one," i.e. a man

separated from his wife.