The ditty probably

originated in the 18th century. Its most familiar modern verses

go as follows:

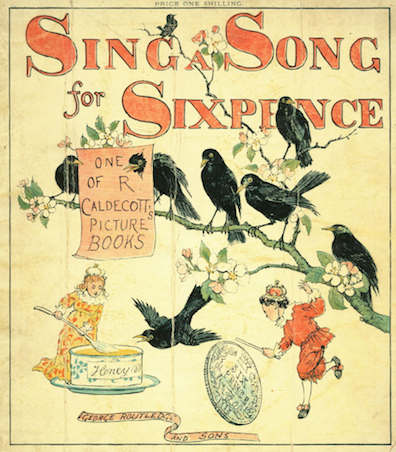

Sing a song of sixpence,

A pocket full of rye.

Four and twenty blackbirds,

Baked in a pie.

When the pie was opened

The birds began to sing—

Wasn't that a dainty dish

To set before the king?

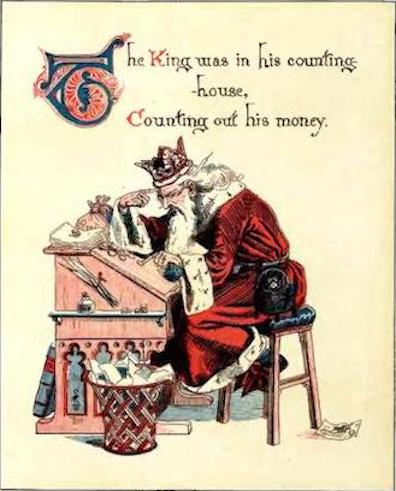

The king was in the counting-house,

Counting out his money;

The queen was in the parlour,

Eating bread and honey.

The maid was in the garden,

Hanging out the clothes;

Along came a blackbird

And pecked off her nose.

The two most disturbing events of the song are the baking of

live birds in a pie (an Italian recipe for such culinary

entertainments survives from the 16th century, and there are

contemporary reports that some were prepared for the wedding

of Marie de' Medici and Henry IV of France in 1600), and the

mutilation of the maid's face. But Joyce focused on three

other, seemingly benign details, finding in each one elements

of Bloom's intimate adult concerns.

One allusion to the song comes when Bloom is preparing to sit

down in the outhouse: "He kicked open the crazy door of the

jakes. Better be careful not to get these trousers dirty for

the funeral. He went in, bowing his head under the low lintel.

Leaving the door ajar, amid the stench of mouldy limewash and

stale cobwebs he undid his braces. Before sitting down he

peered through a chink up at the nextdoor window. The

king was in his countinghouse. Nobody." With no one

visible next door, the paterfamilias takes his seat upon the throne and voids his bowels,

reflecting with satisfaction that the constipation from which

he suffered on the previous day has now lessened its grip.

It is surely relevant here that Sigmund Freud, in "Character

and Anal Eroticism" (1908), argued for an association in the

unconscious mind between feces and money. Joyce had already

displayed an interest in the ideas of this essay when he wrote

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. In Joyce

Between Freud and Jung (Kennikat Press, 1980), Sheldon

Brivic applies some of them to reading the sentences in which

Stephen, newly enriched by school prizes, tries to order his

world by controlling the flow of money: "In his coat pockets

he carried . . . chocolate for his guests while his trousers'

pockets bulged with masses of silver and copper coins. . . .

the money ran through Stephen's fingers. . . . He had tried to

build a breakwater of order and elegance against the sordid

tide of life without him and to dam up, by rules . . .

interests . . . and new filial relations, the powerful

recurrence of the tides within him. Useless. From without as

from within the water flowed over his barriers" (45).

In Bloom's recollection of the line about the king counting

his money, this association between the flow of money and the

flow of excrement becomes more directly connected with

sexuality. The complex, according to Freud, is rooted in

childhood experiences. Training children to use the toilet

constitutes a crucial moment in the "anal phase" of their

psychosexual development. Prior to this moment, children have

an attachment to their own feces, as things that they have

produced. (In Finnegans Wake Joyce presents Shem the

Penman as an artist whose works are written with excrement on

his own body.) But in potty training children are wheedled and

shamed into relinquishing these precious parts of themselves.

If they resist the adult instructions, the experience of

retaining the excrement within the anus may produce sexual

pleasure, and such individuals mature into adults who derive a

quasi-sexual pleasure from holding onto money. Leopold Bloom,

it may be noted, is notoriously tight with a ducat, and his eroticism is distinctly anal.

Given Bloom's anal eroticism, given his wife's disinterest in

it ("its a wonder Im not an old shrivelled hag before my time

living with him so cold never embracing me except sometimes

when hes asleep the wrong end of me not knowing I suppose who

he has any man thatd kiss a womans bottom Id throw my hat at

him after that hed kiss anything unnatural where we havent 1

atom of any kind of expression in us all of us the same 2

lumps of lard before ever Id do that to a man pfooh the dirty

brutes the mere thought is enough I kiss the feet of you

senorita theres some sense in that"), given the sexual

dysfunction that consequently exists in the marriage, and

given the alienation that will result from Boylan's visit on

this day, it seems appropriate that Bloom thinks of the

nursery rhyme at a moment when he and Molly are in separate

rooms, doing separate things. In Lotus Eaters the

lines about the queen float back into Bloom's head as he

remembers Molly lying in bed eating the slices of toast he

brought her and reading Boylan's letter: "Mrs Marion

Bloom. Not up yet. Queen was in her bedroom eating bread

and."

Bloom of course has his own extramarital fascinations, and

the nursery rhyme manages to embrace those as well. Its

picture of the maid "in the garden, / Hanging out the clothes"

is reproduced physically in the actions of the young woman

whom Bloom stands beside in the butcher's shop. He recognizes

her as "the nextdoor girl," a servant recently employed by his

neighbours on Eccles Street: "His eyes rested on her vigorous

hips. Woods his name is. Wonder what he does. Wife is oldish.

New blood. No followers allowed. Strong pair of arms. Whacking

a carpet on the clothesline. She does whack it, by

George. The way her crooked skirt swings at each whack."

When Bloom exits his back door to go to the outhouse, this

attractively aggressive young woman enters his thoughts again

via the strains of the nursery rhyme: "He went out through the

backdoor into the garden: stood to listen towards the next

garden. No sound. Perhaps hanging clothes out to dry. The

maid was in the garden. Fine morning." His

voyeuristic delectation of this "nextdoor girl" that he has

seen in the backyard anticipates his looking up from the yard

"at the nextdoor window" later in Calypso, forming

a perfect circularity among the three figures in the song.

"Sing a song of sixpence" describes an unhappy love triangle

as evocatively as do any of Bloom's thoughts about Boylan and

Molly later in the novel.