The nameless "White slip of paper" that Bloom checks in Calypso,

to make sure that it is "Quite safe" inside the leather

sweatband of his hat, figures more prominently in Lotus

Eaters. There, it turns out to be not really a slip of

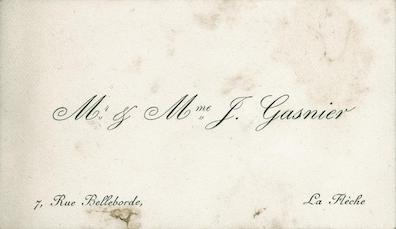

paper but rather a "card"—what Victorians and Edwardians

called a "calling card" or "visiting card," the equivalent of

our "business cards" today. Bloom presents it at the post

office to collect poste restante mail from his erotic

pen pal Martha Clifford, under a pseudonym. Before entering

the post office, in a performance calculated to remove any

suspicion about his clandestine correspondence he moves the

card from his hat to a pocket of his vest. It is one of

several moments in the book when Bloom sees himself as others might

and takes ingenious and probably excessive precautions to hide

his intentions from them.

The first-time reader of Calypso cannot know what

to make of the paper, other than to note that Bloom thinks he

has hidden something well. Lotus Eaters reveals the

card's true nature when Bloom hands it "through the brass

grill" of the post office window, asking "Are there any

letters for me?" When he reads the envelope that is handed to

him, it becomes clear that he carries in his hat a card

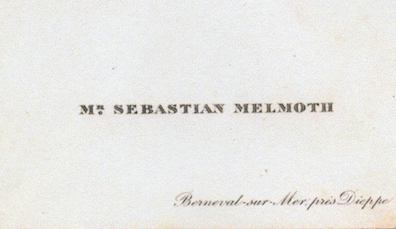

bearing the name "Henry Flower,

Esq." The calling cards of the day sometimes bore simply the

person's name, and sometimes added an address. Henry lists his

address as the Westland Row post office box.

Bloom, then, has invented a respectable alias to cover his

epistolary affair; he has set up a postbox for the fictive

Henry at a site far removed from his own neighborhood; and he

has apparently had cards printed to avoid having to pronounce

the name Henry Flower in a public setting where someone who

knows that he is not Henry might hear him saying it. To make

even more sure that he will not be detected, before entering

the post office he checks to see that there is no one but the

postmistress in the lobby: "From the curbstone he darted a

keen glance through the door of the postoffice. Too late box.

Post here. No-one. In."

Nor is that the end of his Odyssean cunning. While he is

still across the road from the post office he enacts an

elaborate charade to move the card, by sleight of hand, to a

place that a respectable gentleman might keep such an item: "he

took off his hat quietly inhaling his hairoil and sent his

right hand with slow grace over his brow and hair. Very warm

morning. Under their dropped lids his eyes found the tiny

bow of the leather headband inside his high grade ha. Just

there. His right hand came down into the bowl of his hat.

His fingers found quickly a card behind the headband and

transferred it to his waistcoat pocket." Once more

he thinks, "So warm," and (in a Gabler

textual emendation that makes much better sense of the

following sentences and is adopted on this website) he once

more passes his hand over his brow and hair and returns the

hat to its rightful place.

Of this remarkable performance, Peter Kuch writes in Irish

Divorce: Joyce's Ulysses (Palgrave Macmillian, 2017)

that "It is now eleven o'clock, and it is warm but not hot.

But by pretending it is 'rather warm,' Bloom devises a

sequence of gestures that will conceal what he is actually

doing—that is, transferring the card from his hat to his

waistcoat. All his gestures become self-consciously

choreographed. . . . What had been a quick and somewhat

furtive action before breakfast has become, barely an hour

later, a subterfuge that is as complex as it is

self-consciously orchestrated, performed meticulously as it

were before a wholly imagined audience" (75).

A smaller but very similar

charade in Lestrygonians shows Bloom

disguising his intentions not to preserve his sexual

reputation but to guard against offending others. In their

defensiveness both passages seem to anticipate the

hallucinations of Circe, where Bloom is repeatedly

accused of doing shameful things.