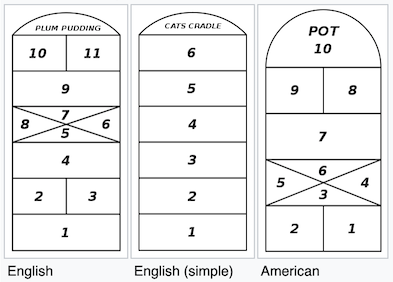

In the familiar game of "hopscotch," children either

scratch into dirt, or mark onto pavement with chalk, a

sequence of numbered spaces ending in a "safe" or "home"

space. The game begins with a player tossing a small stone or

some other flat marker into the first square and hopping

through the sequence on one foot without touching the square

that the stone occupies. (When two spaces lie side by side,

both feet are used as long as neither square contains the

stone.) At the end of the course, the player turns around in

the safe space and repeats the sequence in reverse, bending

over to pick up the stone on the way back. Then the stone is

thrown into the second square, and the third, and so on

through all the numbers. The turn ends when the thrown stone

misses the required square or touches a line, or when the

player's feet do the same thing. After other players have had

their turns, the next turn starts from the point where the

last one broke off. The first player to complete all the

sequences wins the game.

In Ireland the stone was called a "pickeystone" or piggy. Bloom sees a stone

still lying in the maze, a sign that some children were

recently playing there, as he walks over the court "With

careful tread," no doubt making sure not to step on any

lines. The subtle evocation of remembering childhood continues

as he recalls the chant that, according to Gifford, opposing

players would yell at the child who stepped on a line: "You're

a sinner; you're a sinner." His thought, "Not a sinner,"

shows him still defending himself in imagination against these

loud jeers from his God-fearing Catholic playmates. One

imagines Bloom not having been physically graceful or hugely

popular as a child, so he may have endured this verbal

gauntlet with some discomfort.

The game of "marbles" is played with small balls made

of stone, clay, or glass, painted in bright colors or marked

with colorful stripes. A circle several feet in diameter is

drawn on the ground with chalk or string. Marbles called

"ducks" are placed near the center of the circle, sometimes in

a pattern. Players take turns holding another marble in a hand

pressed to the ground and launching it in hopes of knocking

one of the ducks out of the ring but keeping the shooter

marble inside it. Players collect any marbles they succeed in

knocking out of the ring and, as in hopscotch, they keep

shooting until they miss. At the end of the game, the player

who has collected the most marbles wins. (In some versions of

the game the shooter marble is removed at the end of each

turn. In other versions it is not. In "friendlies," the

marbles that have been won are returned to the children who

brought them. In "keepsies" they are not.)

The shooter marble, which is usually large and heavy to carry

more momentum, is called the "taw." The child in Lotus

Eaters is launching it in a particular manner: "shooting

the taw with a cunnythumb." The connotations of this

last word may possibly be negative. Slote notes that "cunny"

is "pejorative for a woman," and, citing the phrase

"cunny-thumbed" in Eric Partridge's Dictionary of Slang,

he suggests that Joyce's word involves "the stereotype that

women clench their fists to punch with the thumb enclosed in

their fingers." By this reading, the child that Bloom sees

kneeling on the ground has a weak, effeminate way of shooting.

If Bloom recognizes the technique and the name, it may remind

him of his own play, because he was not skilled in the game.

Five sentences later he thinks, "And once I played marbles

when I went to that old dame’s school."

The pejorative connotations of "cunnythumb" need not remain

conjectural. It was one recognized way of shooting marbles.

The website of the American Toy Marble Museum shows an

illustration of the technique and makes this comment: "If

Little Lord Fauntleroy played marbles, any boy could tell you

how he would shoot. He would hold his hand vertically; place

his taw or shooter against his thumb-nail and his first

finger. He would shoot 'cunny thumb style,' or 'scrumpy

knuckled.' The thumb would flip out weakly (Fig. 5), and the

marble would roll on its way."

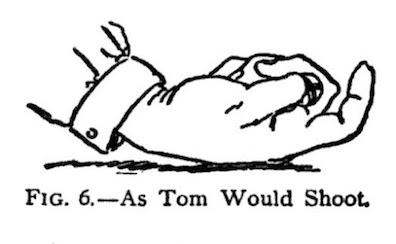

Much better would be the virilely effective style of a Tom

Sawyer or a Huck Finn: "Tom Sawyer would lay the back of his

fist on the ground or on his mole-skin 'knuckle dabster,' hold

his taw between the first and second joints of the second

finger and the first joint of the thumb, the three smaller

fingers closed and the first finger partially open (Fig. 6).

From this animated ballista the marble would shoot through the

air for four or five feet, alighting on one of the ducks in

the middle of the ring, sending it flying outside, while the

taw would spin in the spot vacated by the duck. Tom or Huck

Finn would display as much skill with his taw as an expert

billiard player would with the ivory balls."

In addition to cries of "You're a sinner," then, Joyce's

sentences may possibly evoke fears of shooting like a girl.

Children's games afford endless opportunities for humiliation,

and it does not take much imagination to draw a line from

Bloom's childhood experiences to his present-day experiences

of having to defend himself against charges of cuckoldry, effeminacy, ethnic inferiority, and

political disloyalty.

[2023] A personal communication from David Rayner, though,

suggests that there may be nothing negative about the word

"cunnythumb." In Rayner's childhood in Warrington, a northern

English town between Liverpool and Manchester, the game of

marbles was called "cullies." This usage was apparently common

in Scotland. A 1952 entry in the Dictionaries of Scots

Language defines "cully" as a shooter marble (equivalent

to "taw" in Joyce's text) and "cully-thumb" as "a boy's term

for shooting a marble off the middle of the forefinger instead

of off the tip in the usual manner." The entry notes that

these usages appear to derive from "Eng. slang cully,

a fellow, companion." If Joyce's Irish slang has sprouted from

such roots (and the history of emigration between Ireland and

Liverpool makes that seem quite possible), then there is

probably no implication of effeminacy.