Some of the

Citizen's Irishisms are colloquial enough. When his dog starts

growling he says, "

Bi i dho husht" (

Bi i do

thost), or "Be quiet!" When Joe Hynes asks about his

health he replies, "Never better,

a chara"—"my

friend." He repeats the phrase later when Hynes offers him a

drink: "I will, says he,

a chara, to show there's

no ill feeling." Later, Hynes compliments him on being the man

who "made the Gaelic sports revival" and who set records in the

shot put, prompting him to say, "

Na bacleis"

(

ná

bac leis),

or "Don't bother about it." When Bloom

boldly challenges his bigotry he says, "

Raimeis" (

ráiméis),

"Nonsense!" or "Foolish talk!"

The last two of these words, however, had long entered into

Anglophone speech, in forms like "nabocklesh" and "rawmaish."

Dolan includes both in his

Dictionary of Hiberno-English. Among

uses of the latter he cites this: "Don't be talking raumaish; I

know exactly what happened." Not only had Anglicized versions of

ráiméis long been staples of Hiberno-English, but that

word was also circulating prominently in print journalism at the

turn of the century. Citing F. S. Lyons'

Culture and Anarchy

in Ireland 1890-1939 (Oxford, 1979), Gifford observes

that it "was made into a household word for cant by D. P. Moran

in

The Leader," a Dublin newspaper established in 1900.

Moran used it for the widespread "pretense and humbug" which he

was fighting. The Citizen, then, could be drawing on a

well-known staple of the English of his city rather than on

extensive knowledge of the Irish language.

The same can be said of "

Sinn Fein!...Sinn

fein amhain!" (

sinn féin amháin). The meaning

is "Ourselves! Ourselves alone!"—i.e., Ireland for the Irish,

without the English

stranger.

But, as Gifford notes, this was a common patriotic toast and the

motto of the Gaelic League. It was also the refrain in a famous

song titled

The West's Awake, about the movement to

"wake the old tongue of the Gael; / The speech our fathers loved

of yore." The Irish language, according to the song, was made

"weak and low, / O'ermastered by its foreign foe." But now

"We've won the fight;

Sinn Fein Amhain!" and people can

see "How strong and great 'tis bound to be!" Well, perhaps. The

song itself is written in English, and the Citizen need only

have listened to it, or hoisted a few glasses with his Gaelic

League friends, to learn the Irish phrase.

The outright misunderstandings of Irish begin when Joe Hynes

hands around some pints and the Citizen says, "

Slan leat"

(

slán leat), literally "safe with you." This Irish

way of saying "goodbye" to someone who is leaving (

slán agat

is used when the speaker is leaving) would be wildly

inappropriate as a response to someone who just bought you a

drink. A far more fitting reply would be "

Go raibh maith agat,"

or "Thank you."

Another dubious use of Irish comes when the Citizen, warming up

for his assault on Bloom, unleashes a string of invectives

against Josie Breen's husband, who is not in the bar. The

intention behind the first two seems clear enough: "

a half

and half" and "

A fellow that's neither fish nor flesh"

imply that Dennis Breen is somehow deficient in manhood, despite

his bevy of children. Similar charges are later made more

explicitly about Bloom when he steps out of the bar: "— Do you

call that a man? says the citizen. / — I wonder did he ever put

it out of sight, says Joe. / — Well, there were two children

born anyhow, says Jack Power. / — And who does he suspect? says

the citizen. / Gob, there's many a true word spoken in jest.

One

of those mixed middlings he is."

But, not content with "half and half," the talkative bigot

cannot resist showing off his knowledge of the native

vernacular: "

A pishogue, if you know what that is." Not

only was this word well known to people who did not speak any

Irish (hence the lack of italics), but the Citizen himself seems

not to know what it is. Pishogue or pishrogue (Hiberno-English

equivalents of the Irish

piseog or

pisreog) was

a peasant superstition about witchcraft. It usually meant a

charm or spell, but it was sometimes applied to the people

(typically old women) who cast the spells, or to the mistaken

belief in such witchcraft, in a sense synomous with "an old

wives' tale." One of Dolan's citations notes that country people

often invoked the idea to explain shortages of butter in their

churns: a neighbor must have cast a pishogue to steal the good

stuff.

None of this appears relevant to the Citizen's desire to asperse

Breen's manhood, though Gifford tries to link them, speculating

that the word might refer to "one who is bewitched." Declan

Kiberd too argues that "pishogue" could mean "by extension, a

man 'away' with the fairies." But the word was seldom if ever

applied to people being hexed, and there are no accounts of

pishogue spells having been used to impair virility.

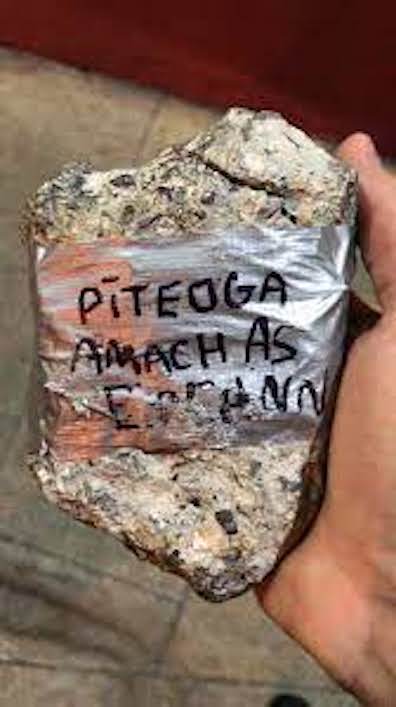

It seems much more likely, as Paul O. Mahoney notes in "The Use

of 'Pishogue' in

Ulysses: One of Joyce's Many

Mistakes?,"

JJQ 47.3 (2010): 383-93, that the Citizen

is thinking of another word,

piteog, that looks like

piseog

and sounds almost identical (pit-YOHG) but means something very

different. Dolan defines it as "an effeminate man or boy, a

sissy; a weedy, insignificant man," as in: "That piteog's always

using after-shave or perfume or something." This word is more

purely Irish. A native Gaelic speaker might use it if he did not

know English words for unmanly men, but it is not a staple of

Hiberno-English speech. Perhaps the Citizen has heard it in

someone's mouth and confused it with the more familiar

"pishogue."

Mahony remarks on the word's broad range of potential

applications: "It typically describes someone who is remarkably

unmanly in any way; it can cover homosexuality, sexual deviancy,

or simply a particularly odd quality or quirk of character. In

some instances, it preserves the ambiguity, increasingly

obsolete in English, of the word 'queer'. In most contexts,

lighter terms of disparagement such as 'nonce' or 'nancy-boy'

would approximate, but not quite translate, its meaning....A

piteog

could be a lad who shies out of tackles during football training

or a man in a mackintosh hanging around a schoolyard" (385).

Mahoney observes that this constellation of qualities seems well

suited to Dubliners' dislike of Bloom, who is suspected not only

of sexual inadequacy but also of other kinds of

untrustworthiness.

The sexual implications predominate in

Cyclops, and

they return in

Circe when "pishogue" is once again used

in a context where

piteog would be more appropriate.

Just before Boylan invites Bloom to

look through the keyhole and

masturbate while he fucks his wife, Molly uses the word to

demean her spouse: "

Let him look, the pishogue! Pimp!"

But if the implications of the one word are being mistakenly

mapped onto the other, the question arises, who is making the

mistake? The repetition of the error in a second character's

mouth would suggest that the defective knowledge of Irish may be

Joyce's, not the Citizen's. Mahoney tentatively endorses this

reading: "Inasmuch as Joyce's usage is a continuing puzzle, the

best explanation may be that he simply made a mistake" (389).

This could well be so—not even James Joyce is perfect—but a

strong case can be made for the contrary view. Molly's mistaken

"pishogue" may simply echo the Citizen's language, since on

every page

Circe voraciously recycles the words and

phrases of earlier chapters. It makes sense that she would do

this in the very moment when her emasculating humiliation of

Bloom confirms the Citizen's view of him as unmanly.

It is also plausible to suppose that Joyce could have known both

words.

Piteog hails from Galway, so he might have

learned it from Nora, and his knowledge of Irish has

consistently been underestimated. As Brendan O'Hehir writes at

the beginning of his preface to

A Gaelic Lexicon for

Finnegans Wake (1967), "the undesigned revelations of

Stanislaus Joyce have shown that his brother left Ireland with a

better initial knowledge of the language of his ancestors than

anyone had previously supposed. The Irish lessons James Joyce

submitted to, for instance, lasted sporadically for about two

years rather than the single session Stephen Dedalus undertook:

with Joyce's linguistic flair even a desultory attention for so

long would have given him at least a modest competence in

Irish."

Assuming that Joyce had sufficient knowledge of Irish, it

would be very like him to skewer a character by making him get

just one letter wrong and then say, "A pishogue, if you know

what that is." And it would cohere with his skepticism about

the Gaelic League project of promoting the revival of Irish.

In Telemachus Haines, an Englishman, speaks Irish to a

peasant woman who should understand him, according to Celtic

Revival mythology, but who instead says, "Is it French you are

talking, sir?" In Cyclops the Citizen reaches for an

Irish expression to express his contempt for unmanly men and

instead evokes a peasant superstition about stolen butter. His

blunder, if such it is, suggests that he speaks Irish very

poorly, and also that linguistic traditions smashed by the

imperial steamroller are as difficult to recover as peasant

folklore swamped by urban modernity.

Many thanks to Vincent Altman O'Connor for his helpful

suggestions about the Citizen's misunderstandings of slán

leat and "pishogue."