The Victorians were by no means the first to practice what is

sometimes called florigraphy or floriography. The Song of

Songs and other books of the Hebrew Bible suggest that

something similar may have been known in ancient Israel. Japan

has an art called hanakotoba that assigns particular

emotions to different flowers. Ancient Greece and Rome

identified symbolic meanings of flowers that were later

revived in the iconography of medieval and early modern

Christianity and chivalry. In Ottoman Turkey a tulip craze in

the early 1700s, following the European one of the 1630s,

inspired a passion for sélam, or flower-messaging,

that became well-known in western Europe. There are probably

many other examples around the world.

Shakespeare's Hamlet shows that the practice began

in England even before the tulip mania. In her mad scene

Ophelia hands out flowers and herbs to Laertes, Claudius, and

Gertrude: "There's rosemary, that's for remembrance; pray you,

love, remember. And there is pansies, that's for

thoughts....There's fennel for you, and columbines. [To

Gertrude.] There's rue for you, and here's some for me;

we may call it herb of grace a' Sundays. You may wear your rue

with a difference. There's a daisy. I would give you some

violets, but they wither'd all when my father died"

(4.5.175-85). Ophelia herself explains the significance of

rosemary and pansies, and scholars have added that fennel

signified flattery, columbine ingratitude, rue regret and

repentance, daisies untruthfulness, and violets faithfulness.

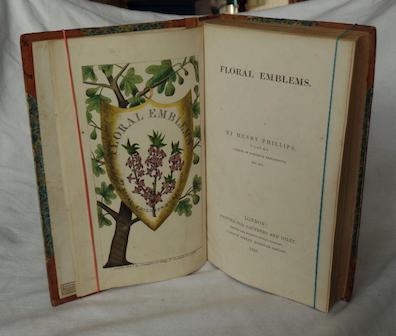

After 1800 such codes became wildly popular first in France

and then in Britain. Books on the subject, some of them simple

dictionaries and others more discursive, included Joseph

Hammer-Purgstall's Dictionnaire du language des fleurs

(1809), Madame Charlotte de la Tour's Le Langage des

Fleurs (1819), Henry Phillips' Floral Emblems

(1825), Frederic Shoberl's The Language of Flowers; with

Illustrative Poetry (1834), Robert Tyas' The

Sentiment of Flowers; or, Language of Flora (1836), John

Ingram's Flora Symbolica; or, The Language and Sentiment

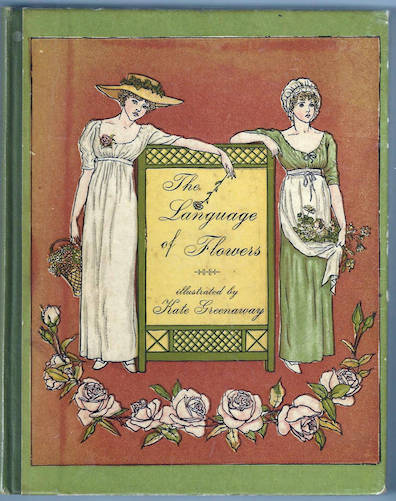

of Flowers (1869), an anonymous volume titled Floral

Poetry and the Language of Flowers (1877), and another

anonymous book called The Language of Flowers (1884),

illustrated by Kate Greenaway, that has been more or less

continuously reprinted to the present day. Americans joined

the craze and published still more books. The enthusiasm was

no doubt fed partly by voyages of exploration which were

bringing tens of thousands of species of exotic plants to

western nurseries and greenhouses, sparking a boom in the

flower trade.

As he re-reads Martha's letter, Bloom calls on his knowledge

of the fad to generate a parallel string of thoughts in

interior monologue: "Angry tulips with you darling

manflower punish your cactus if you don't please poor

forgetmenot how I long violets to dear roses when we soon

anemone meet all naughty nightstalk wife Martha's perfume."

Some of these details appear to translate Martha's thoughts

into conventional floral idioms, though explanation of the

associations is tricky for several reasons: the various

compendia often disagreed with one another; flowers with

multiple species or cultivars (e.g., roses and tulips) could

have different meanings assigned to different colors; Bloom's

florigraphic knowledge may be limited; and Joyce's artistry is

always quirky, subtle, and multifarious. In some instances,

moreover, Bloom seems to be deliberately ignoring the

dictionaries and inventing his own symbols, which say as much

about his states of mind as about Martha's.

Tulips were a vehicle for declaring passionate love, but

Bloom takes Martha's language ("I am awfully angry with you")

as a prompt to turn them into "Angry tulips." This

association does not seem to come from the dictionaries. Anger

was sometimes associated with petunias, and more often with gorse. (Gifford thinks that

tulips could signify "dangerous pleasures," but he does not

cite a source.) The "forgetmenot" symbolized just what

its name suggests, a lover's plea to be remembered (Martha has

called herself "poor me" and urged Bloom to "Remember"). The

idea of faithfulness still inhered in "violets" as it

did in Shakespeare's time, though they could also express

modesty or watchfulness, and "roses" indicated love.

Different kinds of "anemone" could symbolize sickness,

expectation, withered hopes, or the fear of being forsaken—all

appropriate to Martha's situation. In these five flowers Bloom

seems to be recalling details of florigraphy that fit her

feelings, with only slight elaboration.

But in three other flowers he appears to be thinking

inventively of his own sexuality. Imagining himself as "you

darling manflower" does not evoke a known botanical

species, so it should probably be taken as an allusion to the

name Henry Flower ("I often think of the beautiful name you

have"). Bloom's pseudonym carries erotic implications, and at

the end of Lotus Eaters his sexual organ will be

called "a languid floating flower," so "manflower" may be read

as a synechdoche associating him with his penis. The cactus

may carry similar suggestions, given the tubular shape of many

members of this family. It signified warmth in some of the

compendia, but that would hardly explain the desire to "punish

your cactus" (an echo of Martha's "I will punish you").

If Bloom is improvising, the cactus may be his representation

of the sexual urges that led him to include a dirty word in

his last letter, prompting Martha's faux anger. (In addition

to the phallus, Gifford suggests that the cactus might refer

to "touch-me-not," the Mimosa pudica plant whose

leaves curl up when touched. I have not found any evidence of

this identification, and the florigraphic meaning of mimosa,

sensitivity, does not fit the context well.)

Finally, Martha's teasing adjective for her "naughty" darling

Henry becomes associated with yet another plant that cannot be

found in the dictionaries: "all naughty nightstalk."

Gifford supposes that this refers primarily to the phallus,

and secondarily to the large family of plants called

nightshades, which could signify falsehood. (In the Greenaway

book, by contrast, they mean truth.) The first meaning seems

stronger. At night a man's penis becomes a stalk and then is

very naughty indeed. If one accepts that Martha Clifford may

be a veiled allusion to Margaret

Clowry, "nightstalk" also suggests the sexual predation

of a Dublin policeman named Henry Flower who in 1900 was

accused of murdering a young woman, at night, along the

riverbank where he had stalked her. (She had a flower pinned

to her coat.) Such a reading would be consistent with the

phallic suggestion and would cohere with Martha's wish to

"punish" Henry.

In addition to this dense passage in Lotus Eaters, the

language of flowers surfaces at least twice more in Ulysses.

In Wandering Rocks Blazes Boylan takes "a red

carnation" from a vase in Thornton's and asks the girl

waiting on him, "This for me?" She says yes, and he puts the

flower stalk "between his smiling teeth." Carnations of no

certain color signified fascination as well as "woman love" or

"women love," and red ones could mean admiration, or "my heart

aches." This range of meanings seems consistent with the role

that Boylan plays in the novel: loving and being loved by

women, fascinated by them and also fascinating. As he puts the

carnation between his teeth he is staring at the young woman's

breasts and making her blush. When he next appears in Sirens

he is wearing the flower on his coat and Miss Douce, who has

been trying to catch his eye, wonders, "who gave him?"

Molly wonders the same thing in Penelope: "who gave

him that flower he said he bought"? In these chapters

the carnation seems to function as a signifier of sexual

interest—both Boylan's for any attractive woman he sees and

competing women's for Boylan.

In Penelope, just after remembering how she kept

poring over Mulvey's love letter "to find out by the

handwriting or the language of stamps" (two other kinds of

decoding) and just before recalling how she told him that she

was engaged "to the son of a Spanish nobleman named Don Miguel

de la Flora" (one of her many mentions of flowers), Molly

wonders, "shall I wear a white rose." She must be

thinking of the next day, June 17, when she supposes Bloom may

bring Stephen back to visit, because in the final section of

the chapter she makes plans for the visit: "I can get up early

Ill go to Lambes there beside

Findlaters and get them to send us some flowers to put

about the place in case he brings him home tomorrow today I

mean no no Fridays an unlucky day first I want to do the place

up someway the dust grows in it I think while Im asleep then

we can have music and cigarettes I can accompany him first I

must clean the keys of the piano with milk whatll I wear shall

I wear a white rose."

White roses could symbolize innocence, charm, or "I'm worthy

of you," suggesting that Molly is thinking of Stephen as a

possible romantic partner. But at the very end of the chapter,

as thoughts of Bloom proposing to her on Howth Head swirl

together with Mulvey kissing her on the rock of Gibraltar,

both memories sparking thoughts of herself as a "mountain

flower," she reconsiders: "or shall I wear a red yes."

Red roses spoke the language of love and desire. It would

appear that Molly here abandons her virginal fantasy of

becoming a young bride for Stephen and decides to present

herself as she is, a married woman whose love for her husband

has room to accommodate other passions as well.

In "The Language of Flowers: A New Source for Lotus

Eaters," JJQ 26.3 (1989): 379-96, Jacqueline

Eastman comes to many of the same conclusions that I have

inferred in this note, though she bases her readings on only

one of the compendia, Ingram's Flora Symbolica. (It is

an especially complete, thoughtful, and retrospective

production.) Eastman reasons that the long Lotus Eaters

sentence symbolically renders "both the thoughts in Martha's

letter and Bloom's unconscious responses as he rereads. With

well known flowers—tulips, forget-me-nots, violets, roses, and

anemones—Joyce evokes the conventional meaning while in some

cases adding a more personal significance. Furthermore, he

parodies the language of flowers tradition by inventing

several erotically suggestive species of his own" (384-85). I

am not convinced that "parody" is the right word here, but in

general terms our understandings of the two groups of flowers

agree.

Eastman makes a number of interesting observations about

particular flowers. "Tulips" sounds like "two lips," she

notes, suggesting an angry speaking mouth. The physical

appearance of forget-me-nots perfectly conveys Martha's

posture of weak, simpering dependency. The poetry of Robert

Burns gives reason to suppose that violets symbolize modesty.

The phrase "how I long violets" carries also the latent

suggestion "How I long for violence." Love is the principal

meaning of "roses," but the flower's association with thorns

and pins a bit later in the chapter "underscores the

connection between sexual pleasure and pain that exists in

Bloom's subconscious" (387). And the fact that anemones come

at the end of the sequence, shortly before the mention of

Bloom's wife, tie Martha's anxiety about being forsaken to a

very real concern.

Eastman argues that the cactus, which "functions clearly as a

phallic symbol, and one whose thorny stalk evokes pain," also

evokes the phrase coactus volui ("Having been

compelled, I was willing") that is first uttered in the street

by the mad Cashel Boyle O'Connor Fitzmaurice Tisdall Farrell

but is later used by the sexologist Virag in Circe to

express "the overpowering strength of sexual desire" (388).

(Joyce's notesheets, Eastman observes, suggest that it also

made him think of the Italian word for penis, cazzo.)

The "nightstalk," she notes, is echoed in Nausicaa by

a reference to the "Nightstock in Mat Dillon's garden," and

(detecting the same echo heard by Gifford) "inasmuch as the

word reminds the reader of the 'deadly nightshade,' it evokes

Bloom's earlier thought of 'a poison bouquet to strike him

down'" (389).

Two more arguments in Eastman's article deserve mention here.

First, she relates Joyce's familiarity with the language of

flowers (echoed at Finnegans Wake 96.11 as the

"languish of flowers") to other forms of "language as gesture"

in which he clearly took an interest. His notesheets show him

playing with "the language of the parasol, of the umbrella, of

the handkerchief, and of the fan," the last of which he

brought to life in Circe (391). To this important

observation of Eastman's it may be added that Joyce showed

interest in many other nonverbal languages.

Other objects take life as characters in Circe,

including the Cap which challenges Stephen to articulate his

metaphysical understandings of the language of music: "The

reason is because the fundamental and the dominant are

separated by the greatest possible interval which...Is the

greatest possible ellipse. Consistent with. The ultimate

return. The octave. Which...went forth to the ends of the

world to traverse not itself, God, the sun, Shakespeare, a

commercial traveller, having itself traversed in reality

itself becomes that self." Earlier in Circe, Stephen

has spoken to Lynch of still another nonverbal language: "So

that gesture, not music not odour, would be a universal

language, the gift of tongues rendering visible not the lay

sense but the first entelechy, the structural rhythm." In Penelope

Molly refers also to "the language of stamps." In Calypso

Bloom interprets the language of

his cat's meows. There are probably many other examples.

Eastman also remarks at the conclusion of her article that

the language of flowers may account for passages not only in Lotus

Eaters but "throughout the novel" (392). Her sole

example is the "orangeflower" that goes into Molly's skin

lotion and may possibly have some relation to two or three

other passages in the novel involving oranges and orange

blossoms. This is probably not the best example she could have

chosen, as Molly merely likes the scent of these flowers. She

does not pin them to her clothing or send them through the

mail as a coded message signifying something to a special

recipient. (The meaning of orange blossoms, according to

Ingram, is chastity. Eastman can only remark that this is

ironic when applied to Molly.) The examples I have mentioned

here—the carnation that Boylan sports on June 16 and the rose

that Molly plans to wear on the 17th—provide better examples

of floral messaging.