In Lestrygonians Bloom remembers an ad he placed in

the Irish Times: "Wanted,

smart lady typist to aid gentleman in literary work." A

horde of women (or, at least, people presenting themselves as

women) wrote to the man behind the ad (who presented himself

as "Henry Flower, Esq."), seeking employment. Bloom has

replied to 44 such inquiries, and there may be more to come:

"There might be other answers lying there. Like to answer them

all....Enough bother wading through fortyfour of them." He has

begun a correspondence with at least one applicant, seemingly

thinking of erotic involvement rather than employment (though,

as Lotus Eaters continues, it becomes clear that he is

not much interested in physical consummation). Apparently to

assuage the guilt he feels over his false pretenses, he has

begun enclosing small financial gifts in his letters—Martha's

letter asks, "Why did you enclose the stamps?," and when he

replies in Sirens he writes, "Accept my little pres."

Bloom addresses the envelope of this letter to "Miss Martha

Clifford / c/o P.O. / Dolphin's barn lane /

Dublin."

Anyone aware that he has shielded his erotic correspondence

behind the pseudonym "Henry Flower" and a P.O. box distant from

his home address may reasonably suppose that Martha's

information too could be spurious. Bloom himself thinks, in

Nausicaa,

that the name and address "Might be false" like his own. In

Circe

a hallucinated Martha encourages this supposition by declaring,

"

My real name is Peggy Griffin." And in

Ithaca,

when Bloom adds her letter to others in his desk drawer he

thinks of it as "A 4th typewritten letter

received by Henry

Flower (let H. F. be L. B.) from Martha Clifford (find M. C.)."

These details tease readers to "find M. C.," and many solutions

to the puzzle have been proposed, making Martha's identity as

contested as that of

the man in the macintosh. She

may be just who she says she is, but Joyce encouraged other

readings by weaving an astonishing wealth of ambiguous details

into his text.

One of the first critics to propose an alternate identity was

Richard Ellmann, in his biography of Joyce. Ellmann did not

argue that "Martha Clifford" is a pseudonym for some other

person within Joyce's fictional Dublin. He suggested only that

Joyce was transforming another Martha from his own life into a

fictional character. Although his hunt for the real

Martha has turned out to be largely a wild goose chase,

Ellmann did unearth some facts that found their way into the

novel. In December 1918, when Joyce was living with Nora in

Zurich, he was struck by the sight of a young woman in the

bathroom of the adjoining building. A day or two later, he saw

the same woman in the street, walking with a noble bearing and

a slight limp, and felt, Ellmann writes, "that he was seeing

again the girl he had seen in 1898 by the strand, wading in

the Irish Sea with her skirts tucked up. That girl had

constituted for him a vision of secular beauty, a pagan Mary

beckoning him to the life of art which knows no division

between soul and body" (448). Joyce wrote to the woman,

disclosing this vision and begging to meet her.

Her name was Marthe Fleischmann, and "When she realized that

Joyce was in some way distinguished, she wrote to him, and

they began a correspondence that was kept from both Nora's

eyes and Hiltpold's," the latter being a Swiss engineer who

had begun an affair with Marthe after a similar preamble:

anonymous adoration in the streets followed by an exchange of

letters (449). Eventually Marthe agreed to meet Joyce, and on

his birthday, after he staged a ruse fully as elaborate and

sneaky as the ad that has brought Martha to Bloom, the two

seem to have had some kind of sexual encounter. It apparently

did not go as far as intercourse, and after this "they did not

meet again for a long time. They did, however, exchange

letters" (451).

Not just the sublimated letter-writing but many other

Bloom/Martha details parallel the Joyce/Marthe affair. Ellmann

comments that Joyce's "mood in the affair—if the word can be

applied to so uncommitted a relationship—was a blend of

nostalgia, self-pity, and naughtiness" (450). Diagnosed with

glaucoma two years earlier, Joyce (age 37 on 2 February 1919)

felt threatened with infirmity and loss of youthful happiness,

just as Bloom (age 38 in 1904) does. Bloom's complaints (in Sirens

he writes a p.s. containing the words "so lonely") prompt

Martha's pity: "Are you not happy in your home you poor little

naughty boy? I do wish I could do something for you." Joyce

sent Marthe copies of Chamber Music and Exiles,

an exchange reminiscent of the ad from a "literary" gentleman.

He signed his letters to Marthe using Greek rather than Roman

e's in his name, just as the cautious Bloom does when

writing Martha in Sirens: "Remember write Greek ees....

In haste. Henry. Greek ee." And he steered

conversations "to the titillating subject of women's drawers,

in all their variety" (450), provoking coy reproval just as

Bloom does by using a "naughty" word in his last letter.

Ellmann concludes that Marthe's "haughty, naughty

beguilements" (452) figured in Joyce's creation not only of

Martha but also of Gerty MacDowell, to whom he gave the limp.

Struck by this connection, some readers, following a track

laid down by Bloom himself in Nausicaa, have inferred

that Gerty is the "real" person behind Martha Clifford: "Then

I will tell you all. Still it was a kind of language between

us. It couldn't be? No, Gerty they called her. Might be

false name however like my name and the address Dolphin's

barn a blind." The first sentence comes from Martha's

letter. So "It couldn't be?" means, Could I actually have just

been gazing at the woman with whom I have been exchanging

letters? "No," Bloom decides, that could not be, because the

woman's friends called her Gerty. But Gerty could have written

under the psedonym Martha, he thinks, which accounts for why,

in Circe, a hallucinated Gerty MacDowell shows up to

accuse Bloom of falsely enticing her, and a "bawd" accuses her

in turn: "Leave the gentleman alone, you cheat. Writing

the gentleman false letters. Streetwalking and

soliciting." Here Bloom is the literary "gentleman" of the

Henry Flower ad, and Gerty is Martha.

But this hallucination must arise from Bloom's mind: it seems

incredible that the actual Gerty would engage in such immoral

involvement with a married man. The narrative in

Nausicaa observes

that "From everything in the least indelicate her finebred

nature instinctively recoiled. She loathed that sort of person,

the fallen women off the accommodation walk beside the Dodder

that went with the soldiers and coarse men with no respect for a

girl's honour, degrading the sex." (More about the Dodder in a

few moments.) "Martha" cannot be explained so easily.

Nor can she be explained as a fictionalized version of someone

from Joyce's own life, because he published the first six

chapters of

Ulysses, including the passage with the

letter, in

The Little Review from May to October 1918,

months before he first saw the Austrian woman. There can be

little doubt that he consciously echoed his infatuation with

Marthe in

Sirens and

Nausicaa, which were

written and published later, but if his correspondence with her

resembles Bloom's correspondence with Martha in

Lotus Eaters,

it must be supposed a case of life imitating art, rather than

the reverse. If Joyce saw Marthe as a reincarnation of the

(partly? wholly?) fictive girl on the strand in

A Portrait

of the Artist, he may also have seen her as a perfectly

coincidental reappearance of the Martha he had already created

in

Ulysses, and adjusted his behavior accordingly.

Ellman's evidence is not irrelevant to a reading of

Ulysses,

then, but it offers no simple genetic explanation.

How should a reader understand Martha Clifford, then? One piece

of manifestly artistic patterning that seems vital to

understanding Joyce's purposes is the persistent triangulation

involved. Bloom associates her with Gerty, and he also

recurrently links her name with the name Mary. Bloom's wife is

named Marion, so the linking of the two names suggests that he

is not seeking an adulterous exit from his marriage so much as a

recuperative reentry. Martha asks him what perfume his wife

uses, a request which could indicate her

wish to imitate her rival. It

appears that Bloom takes it in this way, because in the

paragraph after he reads her request Bloom thinks of "

wife

Martha's perfume," conflating the two women. In the

paragraphs that follow he remembers a song about "

Mairy,"

and, after again recalling the request in the letter ("What

perfume does your wife use") he thinks, "

Martha, Mary. I

saw

that picture

somewhere..."

Musical associations of Martha and Mary run rampant in

Sirens.

Bloom listens to Simon's moving performance of Lionel's aria

from Flotow's opera

Martha that speaks of "How first he

saw that form endearing, how sorrow seemed to part, how look,

form, word charmed him." He reflects on the coincidence of

having intended to write Martha in the Ormond: "

Martha

it is. Coincidence. Just going to write." But the content

of the aria makes him remember the first time he saw Molly:

"First night when first I saw her at Mat Dillon's in Terenure.

Yellow, black lace she wore." He composes a reply to Martha's

letter, being careful to "write Greek ees," and thinks again of

the song about Mary from

Lotus Eaters: "

O, Mairy lost

the pin of her." The aria's ecstatic climax—"

Co-ome,

thou lost one! / Co-ome, thou dear one!...Come!...To me!"—evokes

his endangered love for Marion far more than a new love with

Martha.

Bloom seems to know that he is seeking a way back to Molly.

After reading the letter in

Lotus Eaters, which has

twice importunately asked, "When will we meet?," he supposes

that he and Martha "Could meet one Sunday after the rosary.

Thank you: not having any.

Usual love scrimmage. Then

running round corners. Bad as a row with Molly." Not

wanting the lies and headaches of an affair is understandable,

but in the history of the human species probably few people who

have gone to the trouble of cultivating an adulterous liaison

have ever thought that consummating it would be as distasteful

as a fight with their spouse. Bloom appears to have both feet

firmly anchored in his marriage, thinking only of how physical

infidelity would inevitably end. And the affair may in fact have

begun in awareness of how dependent he is on his spouse.

The address to which he writes in

Sirens, "

Dolphin's

barn lane," recalls

the

place where Molly first became fascinated with him and

where he first kissed her. Of the 44 women who responded to his

ad, did Bloom select Martha because she says she lives in this

part of town?

The critic John Gordon asks such questions in an article titled

"Bloom at Woodstock: (Henry) Flower Power,"

JJQ 39.4

(2002): 821-28. Tugging on another thread in Joyce's

labyrinthine writing, the essay begins by proposing a source for

the name "

Clifford." It was the surname of the other

woman in a famous romantic triangle of the Middle Ages, King

Henry II's adulterous affair with Rosamond Clifford. Legend has

it that, in order to keep Rosamond hidden from his wife Eleanor,

Henry installed her in a maze-like house on the grounds of the

royal palace at Woodstock, which "after some was named

Labyrinthus, or Dedalus worke"

(822). But Eleanor found her way in, confronted Rosamond, and is

said to have given her the choice of dying by knife or by

poison. In one account, Rosamond's tomb had a poison cup carved

into the stone and was hung with rose-covered tapestries. As he

stands looking at Martha's letter, Bloom thinks of "

roses"

three times (and also of the "

rosary" and "

a poison

bouquet to strike him down," though Gordon does not

mention these details). Gordon argues that the flower enclosed

in Martha's letter—"A yellow flower with flattened petals"—may

well be a yellow rose, which can

signify

infidelity (822). When Martha's name becomes linked to

Flotow's opera

in

Sirens, it becomes

linked also with a Thomas Moore song,

The Last Rose of

Summer, that is used repeatedly in

Martha.

Flowers figure prominently in Bloom's story as well. Gordon

observes that Henry II's family name, Plantagenet, was "said to

have derived from an ancestor's custom 'of wearing a sprig of

flowering broom (called

Genêt in French)

in his cap for a feather'" (821). Bloom, he notes, keeps the

name Henry Flower on business cards in his

hat. When

confronted by the constables in

Circe he produces one of

these pseudonymous cards, takes Martha's "

crumpled yellow

flower" out of his pocket, and says, "You know that old

joke, rose of Castile.

Bloom.

The change of name. Virag. (He murmurs privately

and confidentially.) We are engaged you see, sergeant.

Lady in the case. Love entanglement."

Bloom's entanglement in a maze whose mysterious occupant may be

discovered by an angry wife occupies Gordon for the rest of his

essay. He observes that Molly has multiple threads to follow

into the labyrinth. She knows that she should look through her

husband's pockets ("first Ill look at his shirt to see or Ill

see if he has that French letter still in his pocketbook I

suppose he thinks I dont know

deceitful men all their 20

pockets arent enough for their lies"); she has been

wondering who gave Boylan the carnation he was sporting when he

came to the house; she knows that Bloom is secretly

corresponding with some woman; and she has already rifled

through the desk drawer where he keeps the three letters from

Martha. If she wants to discover the hussy's surname (Bloom has

torn up and thrown away the envelopes), she will have to

decipher the cryptogram in which he has recorded her

address—itself a

boustrophedonic

maze written in text that loops back on itself.

Gordon notes that if Molly were ever to find and confront

Clifford, it would probably result in no more bloodshed than

Bloom's Odyssean discovery of the suitors: "she of course would

only be too delighted to pretend shes mad in love with him that

I wouldnt so much mind Id just go to her and ask her do you love

him and look her square in the eyes she couldnt fool me." Bloom,

he argues, seems to want Molly to discover the secret. Why else

bring home the incriminating flower, put the letters in a drawer

where Molly knows he hides things, and preserve a coded

transcription of Martha's quite easily memorizable address?

"There is a juvenile, secret-handshake-and-code-ring quality

about all this, evidently having more to do with the acting-out

of some half-realized fantasy than with the management of a

serious affair. What more delicious, after all, for a humiliated

husband, than such an adultery-detection scenario, in which his

wife tracks the inamorata to her lair, looks her square in the

eyes, and demands to know, because, in the end and in spite of

everything, she does truly love him, whether the other does

too?" (824). While Bloom is thus inviting Molly to follow

threads leading to a mistress in a place where his romance with

Molly began, he is also recapitulating with Martha a wooing

strategy he employed at that time (putting dirty words in

letters), and Martha is scheming to wear Molly's perfume. No

part of this labyrinth leads out of the existing marriage into a

new one.

Rosamond Clifford lived in the 12th century, so her

identification with Martha can only be called associative or

symbolic. But many readers have wanted to explain Martha as a

pseudonym, as Bloom does: she is someone else in Joyce's fiction

(Gerty MacDowell, Miss Dunne, Nurse Callan, Molly Bloom, even

Ignatius Gallaher), or someone that Joyce knew (Marthe

Fleischmann, an Italian student, Nora Barnacle), or some other

actual person (an actual Irishwoman named Peggy Griffin, or the

novelist Marie Corelli and her semi-autobiographical character

Mavis Clare). Andrew Christensen surveys this critical history

in "

Ulysses's

Martha Clifford: The Foreigner

Hypothesis,"

JJQ 54.3-4 (2017): 335-52, adding his own

theory that "Martha," on the evidence of her letter, is a

foreigner with an imperfect command of English.

Christensen's explanation for the grammatical, idiomatic, and/or

typographical mistakes in the letter (e.g., "I do not like that

other world" and "do not deny my request before my patience are

exhausted") is plausible, and it affords an attractive

alternative to the usual views that "Martha" is simply

unintelligent, or a rotten typist. But none of these efforts to

identify Martha's "real name" leads very far into the textures

of the novel or implies a global rethinking of its purposes.

Gordon's article, which proposes a kind of symbolic analogue for

Martha rather than a literal unmasking, makes far more sense of

things.

One other study packs the argumentative punch of Gordon's and

accounts for a similarly rich web of textual details, but its

symbolic analogue is a contemporary Dubliner rather than a

medieval Englishwoman. In "Martha Clifford: Unveiled?," a paper

read in February 2021 for the James Joyce Centre

(www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZIr8OuSITzc) and in June 2021 for the

International James Joyce Symposium, Senan Molony notes the

almost algebraic structure of the sentence in which the phrase

"find M. C." occurs: "

A 4th typewritten letter received

by Henry Flower (let H. F. be L. B.) from Martha Clifford

(find M. C.)." In the analogical structure called a

proportion, one ratio is said to be equal to another. A:B = C:D,

or A:B :: C:D, means that A is to B as C is to D.

L. B. is fictional, but H. F. is not only Bloom's fictive

pseudonym. In real life

Henry

Flower was a constable in the Dublin Metropolitan Police

who came under suspicion for the murder of a young servant girl

named Bridget Gannon. So "let H. F. be L. B." puts an actual

person in relationship to a fictional one. By the logic of the

proportion, "Martha Clifford" is a fictional person who stands

in the same kind of relationship so some actual M. C. Readers

have to hunt in the newspapers of the time to find Bloom's

real-life analogue. Shouldn't they have to do the same thing to

"find" Martha's?

Molony's candidate is a woman named Margaret Clowry who had a

quite definite connection to Henry Flower: she accused him of

murdering her friend Bridget. In what became known as the Dodder

mystery, Gannon's body was pulled from the River Dodder on the

eastern edge of Dublin in the early morning of 23 August 1900.

The death was initially ruled a suicide ("

found drowned"), but then

Clowry told a policeman that she accompanied Gannon to a meeting

with Flower on the night she died and left her when he suggested

that they would like to be alone.

In the inquest that followed, various pieces of evidence

incriminating and exculpating Flower were presented, and certain

parts of Clowry's accusatory testimony were refuted by other

witnesses. The defendant's barrister, who saw that the case

rested almost entirely on her word, noted that "the girl Clowry

showed that she was

very keen in pressing the case

against

Constable Flower," and he attacked the holes in her testimony.

The grand jury declined to indict Flower, who retired from the

force the next day and apparently left Dublin. Many years later,

in the 1940s, an old woman named Margaret Clowry lay dying and,

on the advice of her confessor, summoned a solicitor to confess

that she had quarreled with Bridget, stolen her purse, and

pushed her into the river.

Molony cites numerous details in

Ulysses that suggest

familiarity with this case, remarking that "Martha Clifford in

the book is generally overlain with death, crime, and

investigation." Of many such details in

Lotus Eaters,

one of the most evocative is the flattened flower that Bloom

finds pinned to Martha's letter. He tears it "

gravely"

from its pinhold and puts it in a pocket. Several paragraphs

later, he shreds the envelope: "he took out the envelope, tore

it swiftly in shreds and scattered them towards the road.

The

shreds fluttered away, sank in the dank air: a white flutter,

then all sank"—"

under the bridge," Bloom thinks

later when he is in the church. These actions evoke what must

have happened on the Dodder, between Herbert Bridge and London

Bridge. On the night she died, Bridget Gannon wore a flower

pinned to her dress. It was found in shreds on the riverbank the

next day, and was taken to be a possible indication that she had

been violently assaulted before she sank into the water.

Margaret Clowry said that it was "

flittered in pieces."

She took it home with her and produced it as evidence in court.

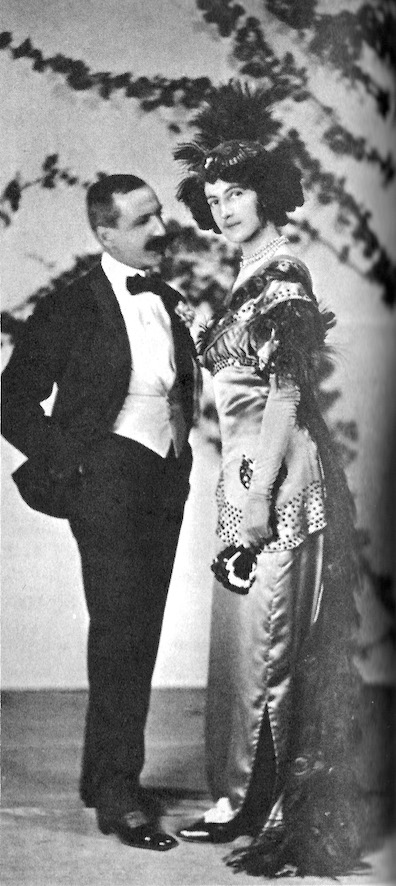

A contemporary newspaper drawing of Clowry shows her wearing a

veil. When Bloom, in

Lotus Eaters, imagines meeting

Martha Clifford he thinks she might "

Turn up with a veil."

One sentence later he thinks, "She might be here with a ribbon

round her neck and

do the other thing all the same on

the sly. Their character." One's natural inclination is to

assume that "the other thing" is sex, but the paragraph does not

show Bloom thinking along these lines. He proceeds instead to

recall the Fenian leader James Carey and the murders committed

by the Invincibles in Phoenix Park in 1882. Carey had a family

and took communion every morning, and yet he was "

plotting

that murder all the time."

When Martha Clifford appears in

Circe, it is as "

a

veiled figure." She speaks, "

(Thickveiled,

a crimson halter round her neck, a copy of the Irish Times

in her hand, in tone of reproach, pointing.) Henry!

Leopold! Lionel, thou lost one! Clear my name." Again one's

first reaction is to think that she wants her name cleared of

the charge of adultery, but again the text suggests something

else because the constable says sternly, "Come to the station."

Is he speaking to Bloom (as Bloom, and the reader, assume), or

to Martha? Molony notes that "Margaret Clowry did go to the

police station—to accuse Henry Flower." Martha, "

sobbing

behind her veil," accuses Bloom of "Breach of

promise.

My real name is Peggy Griffin. He

wrote to me that he was miserable. I'll tell my brother, the Bective

rugger fullback, on you, heartless flirt."

Obviously this accusation speaks to the erotic correspondence,

but "Peggy" is a diminutive of Margaret, "griffin" is slang for

a sports bet or hint, and Gannon died just across the river from

the Lansdowne Road rugby stadium. The love "

scrimmage"

that Bloom has thought he wants no part of, in

Lotus Eaters,

here becomes overlain with a violent scrum next to a rugby

pitch.

There is more to Molony's case, but these salient details may

suffice to indicate how frequently the letter from Martha

becomes associated with "

the body in the water," a phrase

used near the beginning of

Lotus Eaters when Bloom is

thinking about the Dead Sea.

(Molony does not mention another, more overt evocation of the

murder in

Circe. When Henry Flower appears as a

troubadour, plucking a lute and singing "Thine heart, mine

love," he is "

Caressing on his breast a severed female

head.") Such details would have resonated for

Dubliners who recalled the sensational developments in 1900. As

Molony notes, Joyce attended Dublin inquests and trials, and the

daily papers featured copious coverage of the Dodder mystery. In

a moment of typically sly Joycean ambiguity in

Lotus Eaters,

Bloom takes Martha's letter out of the paper in which he has

been concealing it: "

Having read it all, he took it from the

newspaper."

If one accepts Molony's findings, the challenge is how to

interpret them. Is Martha Clifford actually Margaret Clowry,

charging her Henry Flower with murder? Clearly not: Margaret is

to Martha as Henry is to Leopold, a suggestive analogue rather

than a coded equivalence. But even if the identification is

merely symbolic, why would Joyce have made such a strange

connection between adulterous flirtation and murder?

Molony does not take up this question, but there is plenty of

material to work with. Of the mortally grave charges to which

Joyce regularly subjects Bloom in

Circe, many involve

erotic wrongdoing. Martha, Gerty, the maid Mary Driscoll, the

Nymph above the bed, and three high-society ladies all accuse

him of sexual misconduct. Joyce was still beating that drum in

Finnegans

Wake with rumors of what HCE did in the Phoenix Park. This

fictive preoccupation—the dangers of sexual adventure—must have

been rooted to some extent in personal experience. Joyce's

meeting with

Alfred Hunter

was occasioned by an erotic overture in a park that ended with

him being savagely beaten by the young woman's boyfriend. The

affair with Marthe Fleischmann ended with a threatening letter

from her protector Herr Hiltpold, who informed him that Marthe

had been treated at a sanitarium and was blaming Joyce for her

fragile mental state.

Probably the most striking feature of Martha's letter is its

sharp note of accusation ("I am awfully angry with

you"), its talk of punishment ("I do wish I could punish you

for that"), its archly threatening tone ("So now you know what

I will do to you, you naughty boy"). These aggressive notes,

which sit oddly but not implausibly with Martha's plaintive

self-effacement, are usually read as flirtatious ploys: she

has sensed Bloom's masochistic

weakness toward women and has decided to play the role

of disappointed, reproving, but nurturing mother. And that is

probably just how they should be read on the literal level.

But the echoes of the Margaret Clowry affair impose a layer of

symbolic suggestion on top of this realistic correspendence,

just as the echoes of Rosamond Clifford do. Both stories link

erotic adventure with murder. Adultery can be a deadly serious

business.