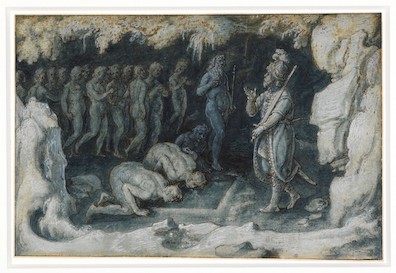

In his detailed Linati schema, Joyce listed more Homeric

"Persons" for Hades than for any other chapter of Ulysses,

suggesting (even if one does not assume significant modern

correspondences for all of them) an intense engagement with

the Odyssey. The story runs as follows: In book 10

Circe advises Odysseus to sail his ship far north to a shore

where four rivers (Pyriphlegethon, Cocytus, Styx, and Acheron)

flow. There he is to dig a small square pit and fill it with

the blood of two sheep, which will attract the shades of

Hades. The Homeric dead are pale shadows of living people

eager for the life-giving force of hot blood, as Bloom thinks

in Lestrygonians: "Hot fresh blood they prescribe for

decline. Blood always needed. Insidious. Lick it up

smokinghot, thick sugary. Famished ghosts." Odysseus

gathers his men to carry out the fearsome task, but before

they can leave Circe's palace one of them, Elpenor, slips from

the roof of the palace, where he fell asleep after drinking

too much wine, and breaks his neck. In book 11, after Circe's

directions are fulfilled, Elpenor's shade comes forward, tells

Odysseus his story, and receives the promise of a decent

burial. The hero then encounters many other shades that come

crowding around the bloody pit.

Hades echoes many visual details of Book 11, as well

as some from Virgil's imitative Aeneid and Dante's

classically oriented Inferno. As the funeral

procession moves through Dublin it crosses four bodies of

water ("Dodder bridge," "The Grand Canal," "the Liffey," "the

royal canal") that recall the four Homeric rivers, as well as

similar waters in Virgil and Dante. The marble shapes in the

stone-cutter's yard next to the cemetery evoke the

shades crowding around Odysseus at the pit, appealing to be

heard: "Crowded on the spit of land silent shapes appeared,

white, sorrowful, holding out calm hands, knelt in grief,

pointing. Fragments of shapes, hewn. In white silence:

appealing." Inside the cemetery, Bloom's "How many!

All these here once walked round Dublin" vividly recalls

Dante's "I could not believe / death had undone so many" (Inferno

3.56-57). There are two more

echoes of the Inferno in this chapter, and

probably one or two of the Purgatorio as well.

The "Gloomy gardens" and "dismal fields" in Joyce's

text recall the Lugentes campi (fields of mourning)

of Virgil's unhappy lovers (Aeneid 6.440). As the

chapter ends, Bloom sees that "The gates glimmered in

front: still open. Back to the world again," echoing the

"two gates of Sleep" which confront Aeneas at the end of book

6, through one of which he goes back to the world again. Still

another Virgilian echo occurs when Simon Dedalus describes

Mulligan as his son's "fidus Achates." The

phrase "faithful Achates" used at Aeneid 1.118 names a

loyal friend of Aeneas, and Simon intends merely a scornful

contrast to Mulligan. But at 6.47-52, Achates and Deiphobe

appear as the advance party that has prepared the way for

Aeneas to descend into the underworld.

Many of Joyce's characters are plainly linked with Homeric

models. Paddy Dignam's

alcoholic death ("Blazing face: redhot. Too much John

Barleycorn") recalls Elpenor's. Simon Dedalus' pride in

Stephen ("Full of his son. He is right. Something to hand

on") recalls the joy of Achilles when Odysseus tells him

how well Neoptolemus spoke and fought in the Trojan campaign.

The married caretaker John O'Connell prompts Bloom to wonder

how any woman could ever have been persuaded to live in a

cemetery: "Fancy being his wife. Wonder how he had the

gumption to propose to any girl. Come out and live in the

graveyard. Dangle that before her." In the Odyssey no

persuasion was involved: Hades raped Persephone, tearing her

away from the sunshine and carrying her down into his gloomy

world.

The echoes go on and on. Bloom's thoughts about his dead

father correspond to Odysseus' conversation with his dead

mother. The silent snubbing that Bloom receives from John

Henry Menton resembles the moment when Ajax silently snubs

Odysseus. The Gilbert schema also suggests correspondences

between Parnell and Agamemnon (great leaders of nations) and

between Daniel O'Connell and Hercules (great heroes). Many

readers have detected other equivalences, with varying degrees

of plausibility.

Several mythological figures from ancient epic underworlds

also figure in Joyce's chapter. Martin Cunningham's marital

situation presents a modern version of the stone-rolling

Sisyphus: "And that awful drunkard of a wife of his. Setting

up house for her time after time and then pawning the

furniture on him every Saturday almost. Leading him the

life of the damned. Wear the heart out of a stone, that.

Monday morning. Start afresh. Shoulder to the wheel."

Another figure of eternal punishment, Tantalus, who is

tortured by fruit that he can never eat and water that he can

never drink, comes up when Bloom thinks that seeing lovers

nearby would be "Tantalising for the poor dead. Smell of

grilled beefsteaks to the starving," and again when he

thinks of "Tantalus glasses." The three-headed dog Cerberus,

who guards the entrance to the underworld, takes the modern

form of the priest Father Coffey. "Bully about the muzzle

he looks," thinks Bloom, "with a belly on him like a

poisoned pup."

These many precise echoes weave a fabric of pagan antiquity

around the Christian cemetery and its rites, paralleling

Bloom's skepticism about a heavenly home. One strong influence

from the ancient epics is the sense of ghostly

insubstantiality that they attach to the dead. Circe calls the

people that Odysseus will meet "the faint dead," and Book 11

describes Erebus as a place where the "dimwitted dead are

camped forever, / the after-images of used-up men." Odysseus

learns that at death "dreamlike the soul flies,

insubstantial," and Tiresias tells him that the dead crave the

blood in the pit because it will give them a brief

substantiality: "Any dead man / whom you allow to enter where

the blood is / will speak to you, and speak the truth; but

those / deprived will grow remote again and fade." The

desperate enervation of this place receives supremely dramatic

expression when the great conqueror of men, Achilles, tells

Odysseus that he would rather "break sod as a farm hand / for

some poor country man, on iron rations, / than lord it over

all the exhausted dead."

Virgil retained the outlines of Homer's underworld while

adding features that Greek eschatology had only dimly

forecast: rewards for well-led lives, torments for wickedness,

and a fully fleshed theory of reincarnation. In Dante's

afterlife, where punishment and reward swell to govern the

entire conception, reincarnation is anathema and there can be

no thought of the mundane world being more real than heaven

and hell. Still, his damned souls do have some of the

desperate insubstantiality of Homer's dead. Even those who

endure no physical torments suffer from awareness that they

eternally lack the presence of God, and Farinata explains that

the damned possess "the mighty Ruler's light" only in being

able to see the future; they are blind to the present, so when

time ends and only the present moment exists, "all our

knowledge will perish" (10.100-8).

Readers can form their own judgements about the relevance of

these various afterlives to Bloom's mortuary reveries. But it

is unquestionable that, like Achilles, Bloom prizes life in

the flesh over the shadowy, uncertain, decaying facsimiles of

life beyond the grave. "There is another world after death

named hell," he thinks. "I do not like that other world

she wrote. No more do I. Plenty to see and hear and feel yet.

Feel live warm beings near you. Let them sleep in their

maggoty beds. They are not going to get me this innings. Warm

beds: warm fullblooded life." The priest's "In paradisum"

means nothing to Bloom: "Tiresome kind of a job. But he has to

say something." Reincarnation makes somewhat more sense: "If we were all suddenly somebody

else." But what makes most sense is that the heart stops

beating, the body falls apart, the person vanishes, and loved

ones start forgetting you.

The oblivion is not total, however. Like the insubstantial

shades of former human beings that populate Homer's

underworld, the dead in Hades live on in ghostly

simulacra, poignant recollections, proud memorials, and loving

wishes. Monuments to great men line the route of the

procession from just below O'Connell

Street to its very end. The palliative fiction of people

lying at rest in the graveyard generates Thornton Wilder-like

fancies about their ongoing life: "The dead themselves the men

anyhow would like to hear an odd joke or the women to know

what's in fashion." Photographs and voice recordings can

perpetuate memories of lost loved ones: "After dinner on a

Sunday. Put on poor old greatgrandfather. Kraahraark!

Hellohellohello amawfullyglad kraark awfullygladaseeagain

hellohello amawf krpthsth. Remind you of the voice like the

photograph reminds you of the face. Otherwise you couldn't

remember the face after fifteen years, say." Perhaps

there are even actual ghosts walking among us, as the

mysterious man in the macintosh does in the Glasnevin

cemetery.

The most enduring effect of Hades, remarkably similar

to the one created by the ending of The Dead, is a

suggestion that the dead are never completely erased from the

world of the living, and the living never completely escape

the dead's capacity for diminishment, loss, and ghostly

insubstantiality. The sixth chapter of Ulysses abounds

with language of life-in-death and death-in-life, limning a

border that Joyce would explore again in Finnegans Wake.

Another pervasive linguistic feature is the repetition

(totaling 23 times) of the word "heart," which both schemas

identify as the "organ" of Hades. The cessation of

this organ's beating signifies the end of life. Its yearnings

create the human condition defined in Yeats' Nineteen

Hundred and Nineteen: "Man is in love, and loves what

vanishes, / What more is there to say?"