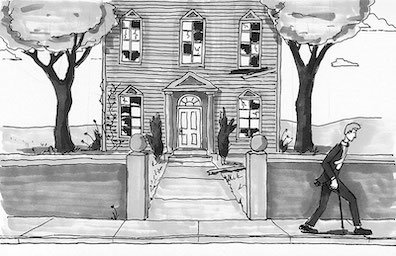

As the funeral

carriage nears its destination, Mr. Powers points out "The last

house" before the cemetery grounds: "That is where Childs was

murdered." The men in the carriage discuss the 1899 trial and

acquittal of Childs's brother Samuel, Martin Cunningham voicing

the legal principle that it is better for 99 guilty people to

escape justice than for one innocent person to be wrongly

condemned:

They looked. Murderer's ground. It passed darkly.

Shuttered, tenantless, unweeded garden. Whole place gone

to hell. Wrongfully condemned. Murder. The murderer's

image in the eye of the murdered. They love reading about it.

Man's head found in a garden. Her clothing consisted

of. How she met her death. Recent outrage. The weapon used. Murderer

is still at large. Clues. A shoelace. The body to be

exhumed. Murder will out.

As the third-person narration that begins this passage gives way

to interior monologue, Bloom repeats two words from the

soliloquy in which Hamlet laments that his entire world has, in

Bloom's words, "gone to hell": "Fie on't, ah fie!

'tis an

unweeded garden / that grows to seed, things rank and

gross in nature / Possess it merely" (1.2.135-37). Hamlet is

brooding on his father's sudden death and his mother's

remarriage to the king's brother, a gross specimen of humanity

"no more like my father / Than I to Hercules" (152-53). An

overgrown garden expresses this decline from Edenic perfection.

The phrase "unweeded garden" is probably no accidental echo

(Bloom knows

Hamlet, and this is one of its famous

lines), but does it allude to the play in any significant way?

Bloom is thinking about murder, but Hamlet presumably is not,

because he has not yet learned how his father died. When Joyce

echoes other texts, however, readers who look for deeper

connections are often rewarded. The man accused of murdering

Thomas Childs was his younger brother, and before act 1 is over

Hamlet learns that his father's younger brother murdered him to

seize his patrimony. Hamlet's soliloquy all but predicts this

revelation, and when he learns from the ghost that "The serpent

that did sting thy father's life / Now wears his crown," he

exclaims, "O my prophetic soul!" (1.5.39-40).

The structural analogy of murderous younger brothers lurks

beneath the surface of Joyce's text, but various phrases in the

text point to it. The newspaper staple "

Murderer is still at

large" is a five-word encapsulation of the charge that the

ghost gives Hamlet. The "

unweeded garden" of Childs's

house recalls the poisoning that took place while King Hamlet

was "

Sleeping within my orchard" (1.5.59). An orchard is

a garden, as Shakespeare makes clear when Hamlet tells Claudius

about the fictional killer of a king in his mousetrap play: "

'A

poisons him i' th' garden for his estate"

(3.2.261). Lurid newspaper details like "

Man's head found in

a garden" are no more sensational than the horrifying

account of bodily dissolution that the ghost imparts to Hamlet.

Finally, the old proverb that "

Murder will out" may, as

Gifford suggests, recall Hamlet's rationale for staging a play

within the play: "

For murther, though it have no tongue, will

speak / With most miraculous organ" (2.2.593-94).

It is hard to say how many, if any, of these analogues to the

murder of King Hamlet may actually occur to Bloom, as opposed to

simply being thrown in his way by the author, but their

cumulative effect is certainly to overlay one murder on another.

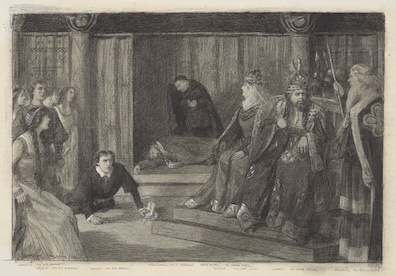

The allusion to Ophelia is opposite. It occurs in a single,

highly uncertain sentence, but one can easily imagine Bloom

thinking it, since he has already

reflected on Ophelia's suicide

in

Lotus Eaters. Bloom is grateful when Martin

Cunningham tamps down the harsh judgments of suicide from Jack

Power and Simon Dedalus:

Sympathetic human man he is. Intelligent. Like

Shakespeare's face. Always a good word to say. They have no

mercy on that here or infanticide. Refuse christian burial.

They used to drive a stake of wood through his heart in the

grave. As if it wasn't broken already. Yet sometimes they

repent too late. Found in the riverbed clutching rushes.

The image that concludes these sentences seems to derive at

least in part from canto 5 of

Dante's

Purgatorio, in which two people in the circle of

the Late Repentant describe how they died at water's edge, one

of them "entrapped in reeds / and mire," the other swept

downstream by a flood and deposited at the muddy bottom of the

Arno. It is not clear why Bloom thinks, "Yet sometimes they

repent too late," but this detail applies well to Jaccopo and

Buonconte, and not at all to Ophelia. Despite the almost certain

presence of Dante in the image, though, it seems that Joyce may

also have had Shakespeare in mind, because Ophelia too was

"Found in the riverbed" clutching vegetation.

Queen Gertrude tells Laertes that his sister drowned in a

"brook." She was weaving "fantastic garlands" out of

wildflowers, and as she strained to hang them on the boughs of a

willow tree overhanging the river, a branch broke. She fell in

still holding her flowers, floated for a while "As one incapable

of her own distress," until her waterlogged clothes "Pull'd the

poor wretch from her melodious lay / To muddy death"

(4.7.166-83).

Gertrude's speech feels like a jewel of ekphrastic verse (it has

inspired many paintings), but it can hardly be an honest

account. If she watched all these things happening, why did she

not intervene to save Ophelia's life? The following scene

suggests why Gertrude might have invented a false story. The

first gravedigger asks why Ophelia is receiving a Christian

burial if she committed suicide, and the second one says that

the coroner has made that ruling (5.1.1-5). Later in the same

scene, Laertes sees someone being buried with "maimed rites" and

infers "The corse they follow did with desp'rate hand / Fordo it

own life" (219-21). The priest escorting the body says that "her

death was doubtful, / And but that great command o'ersways the

order, / She should in ground unsanctified been lodg'd / Till

the last trumpet" (227-30).

It appears, then, that the miserable Ophelia threw herself

into a stream and met an ugly, "muddy death." Bloom's image of

a corpse "Found in the riverbed clutching rushes" is

probably a much more accurate account than the picture that

Gertrude paints of Ophelia clutching pretty flowers. But the

queen's fiction is calculated to spare Laertes' feelings. Like

Martin Cunningham she is "Sympathetic." She shows "mercy,"

finds "a good word to say." Bloom supposes Shakespeare to have

been this kind of man, capable of valuing human suffering over

religious doctrines.