As the funeral carriages start to move at the beginning of Hades,

they pass "number nine with its craped knocker, door ajar.

At walking pace." Houses of mourning were conventionally

decorated with crepe––black in most cases, but white when the

deceased was a child. Ribbons of the fabric were hung from

doorknobs, knockers, or wreaths, and larger swaths were

sometimes draped around windows and door frames. According to

a 2021 blog by Cathy Wallace on the Billion Graves website

(blog.billiongraves.com/preparing-the-victorian-home-for-a-funeral/),

knockers were often covered with the cloth to keep visitors

from disturbing the family with loud noises. "Visitors were

expected to just knock softly. Sometimes the door was even

left ajar so they could just walk in." Joyce's narrative notes

this practice of leaving the door ajar, and adds the further

detail of starting the procession at a walking pace to

preserve the air of quiet solemnity.

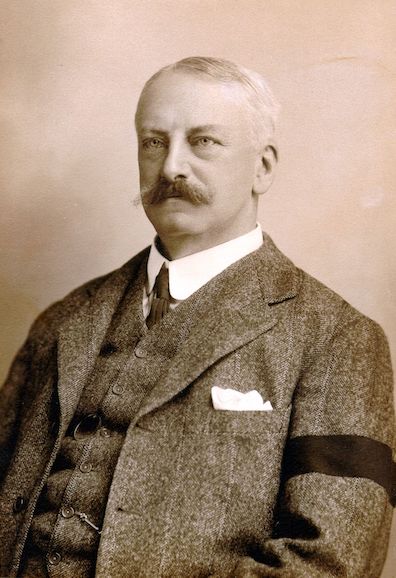

Later, as he looks out the window of the carriage moving down

Great Brunswick Street, Bloom sees "A man in a buff

suit with a crape armlet. Not much grief there. Quarter

mourning. People in law perhaps." Wearing a black crepe

ribbon around a sleeve was another conventional expression of

mourning. Bloom notes the minimal nature of this gesture (at

the other extreme, Victorian widows were expected to dress

entirely in black crape for one year), suggesting either that

this mourner was not very close to the deceased ("People in

law perhaps") or that a considerable amount of time has

elapsed since the death (Victorian conventions prescribed a

period of full mourning, usually for one year, followed by

half-mourning and then "Quarter mourning").

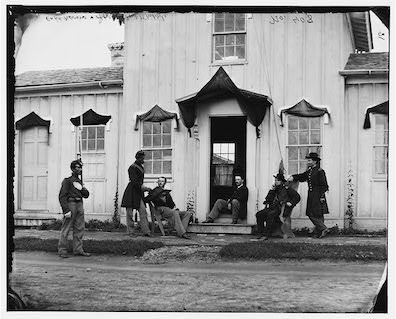

In the cemetery's mortuary chapel Bloom notices "Crape

weepers." These are probably not paid mutes, as

Gifford supposes, but decorative ribbons on people's clothes,

like the armband that Bloom has spotted on the sidewalk of

Great Brunswick Street. Slote cites a definition in the OED:

"Weeper: a badge of mourning, usually on a man's sleeve, but

also around his hat." Just after this, Bloom goes on to take

note of "Blackedged notepaper." Mourners were expected

to write their letters on stationery that was surrounded by a

black border.

Although the narrative does not say so, black crepe may very

well figure also in the two "wreaths" that are loaded

into the hearse at the Dignam house, unloaded at the gates of

the cemetery, and carried into the mortuary chapel. Some

Victorian and Edwardian funeral wreaths were woven from

greenery like yew or laurel and tied with black ribbons, but

others were constructed entirely of folds of crape.

These various codified expressions of grief constituted a

visual language for Victorians and Edwardians, not only

alerting them to the presence of recent deaths in their

communities but also giving them information about when the

death had occurred, what kind of relation the mourner had to

the deceased, and thus how others should regard that person.

In this respect crape functioned in a manner similar to the language of

flowers, which had its own conventional symbols for

grief and mourning. As Bloom walks about Dublin on June 16,

his black suit signifies the possibility of personal loss to

people who do not know him well, prompting solicitous

inquiries like M'Coy's in Lotus Eaters:

His eyes on the black tie

and clothes he asked with low respect:

— Is there any... no trouble I

hope? I see you're...

— O, no, Mr Bloom said. Poor

Dignam, you know. The funeral is today.

The same thing happens when Bloom crosses paths with Josie Breen

in

Lestrygonians, but this time he is content to

encourage her solicitous concern:

— You're in black, I

see. You have no...

— No, Mr Bloom said. I

have just come from a funeral.

Going to crop up all day, I

foresee. Who's dead, when and what did he die of? Turn up like

a bad penny.

— O, dear me, Mrs Breen

said. I hope it wasn't any near relation.

May as well get her sympathy.

— Dignam, Mr Bloom said.

An old friend of mine. He died quite suddenly, poor fellow.

Heart trouble, I believe. Funeral was this morning.

Later in the same chapter, a considerate pub owner waits until

Bloom has gone outside to ask an obtuse customer what kind of

mourning Bloom's clothes may signify:

— I know him

well to see, Davy Byrne said. Is he in trouble?

— Trouble? Nosey Flynn

said. Not that I heard of. Why?

— I noticed he was in

mourning.

— Was he? Nosey Flynn

said. So he was, faith. I asked him how was all at home.

You're right, by God. So he was.

— I never broach the

subject, Davy Byrne said humanely, if I see a gentleman is in

trouble that way. It only brings it up fresh in their minds.

Bloom will wear black clothes only on the day of the funeral,

as he had no close ties to Dignam. Stephen, however, has been

wearing them for nearly a year, as the old strict Victorian

conventions demanded of a grieving son.