Marguerite Alacoque was born in 1647 in Burgundy and became

an intensely pious child. As a teenager, after four years of

debilitating rheumatic fever, she made a vow to the Virgin

Mary (whose name she added to her baptismal name) that she

would become a nun, at which point she is said to have

immediately recovered her health. Several years after that,

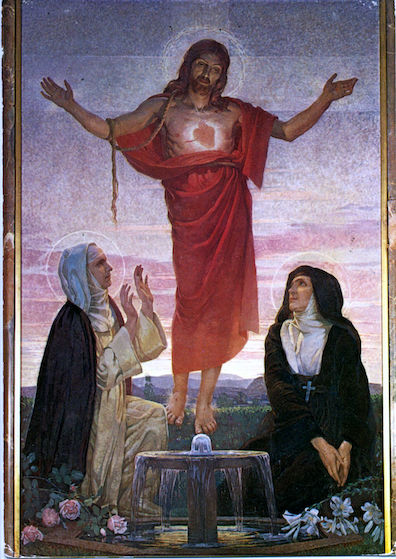

she had a vision in which Christ urged her to fulfill her vow,

telling her that his heart was full of love for her and taking

that heart out of his chest and placing it in hers. In 1671

she entered a convent run by the Order of the Visitation of

Holy Mary, and over the next few years she continued to have

visions of the Sacred Heart. Her superiors slowly came to

accept her visions as authentic, and after her death in 1690

the Jesuits

cultivated her devotion to the Sacred Heart, leading to

official church recognition in the late 18th century. In 1824

Pope Leo XII declared Sister Margaret Mary to be Venerable.

Pope Pius IX beatified her (hence Mulligan's "Blessed") in

1864, and in 1920 she was canonized (made a Saint) by Pope

Benedict XV.

Alacoque's devotional practice became more popular in Ireland

than in any other European country, with the possible

exception of France. In an article titled "The Sentence That

Makes Stephen Dedalus Smash the Lamp," Colby Quarterly

22.2 (June 1986): 88-92, Frederick K. Lang observes that "Ten

other countries would follow suit, but Ireland was apparently

the first to dedicate, or, more properly, consecrate itself to

the Sacred Heart" (90). Joyce, he notes, referred in a 23

October 1922 letter to "the Sacred Heart to whom Ireland is

dedicated" (Letters 1.191). The reasons for the Irish

enthusiasm are obscure, but it was undoubtedly stimulated by

an influential devotional magazine called The Irish

Messenger of the Sacred Heart which the

abstinence-promoting Jesuit priest James Cullen began

publishing in 1888. In Circe Davy

Stephens hawks copies of "Messenger of the Sacred

Heart and Evening Telegraph with Saint

Patrick's Day supplement. Containing the new addresses of all

the cuckolds in Dublin."

In the Dubliners story "Eveline," a "coloured print

of the promises made to Blessed Margaret Mary Alacoque" hangs

on a wall in Eveline's home. In exchange for believers

consecrating their lives to the Sacred Heart, Jesus supposedly

made them twelve "promises," one of which was to bless any

home in which an image of the Sacred Heart was displayed. So

popular was this devotion that most Irish Catholic homes in

1904 appear to have contained Sacred Heart prints. It is clear

that Bloom has encountered these icons on people's walls,

because when he looks at a carved version in the cemetery he

thinks that the heart should be turned sideways and painted

red:

The Sacred Heart that is: showing it. Heart

on his sleeve. Ought to be sideways and red it should be

painted like a real heart. Ireland was dedicated to it

or whatever that. Seems anything but pleased. Why this

infliction? Would birds come then and peck like the boy with

the basket of fruit but he said no because they ought to have

been afraid of the boy. Apollo that was.

§ Jesus's

appearance of being "

anything but pleased" carries

iconographic significance. Lang quotes from

Devotions to the

Sacred Heart, a book published in Dublin in 1841 that

Joyce almost certainly knew: "From the greater number [of

humankind] I receive ingratitude, contempt, irreverence,

sacrilege, and indifference... but what is still more afflicting

is, that I receive these insults from hearts which are

peculiarly consecrated to my service

" (90).

But Bloom is blissfully ignorant of this implied reproach. With

the words "

Heart on his sleeve," he connects the sense of

"infliction" to an unrelated literary work, Shakespeare's

Othello.

In that play's opening scene Iago assures Roderigo that his

devotion to Othello is nothing but a false front disguising

vengeful egoism:

In following him, I follow but myself;

Heaven is my judge, not I for love and duty,

But seeming so, for my peculiar end;

For when my outward action doth demonstrate

The native act and figure of my heart

In complement extern, 'tis not long after

But I will wear my heart upon my sleeve

For daws to peck at: I am not what I am.

(58-65)

By inverting God's "I am what I am" from the book of Exodus,

Iago says not only that his inner nature belies his outward

appearance, but also that he is a kind of Satanic anti-God. This

pithy self-definition coheres with his anti-Christian ethics.

The kind of mutual devotion exemplified by Jesus and Sister

Margaret Mary is anathema to him. Opening up his emotions in

that way, he says, would be like hanging his heart on his arm

for birds to tear at. Having pulled this alternate image of an

exposed heart from his memory, Bloom appears to lean more to

Shakespearean skepticism than to Catholic religiosity. He

projects something like Iago's self-protective scorn onto the

carved face in the graveyard. Jesus, he imagines, does not much

like having his chest wall opened up for females to fawn over.

In fact, he finds it seriously annoying.

The thought of birds pecking at hearts leads him into yet

another irreverent association. The ancient Greek painter Zeuxis

(ca. 464-ca. 400 BCE) was reputed to have painted some grapes

with such perfect

trompe l'oeil realism that birds flew

at the canvas trying to eat them. In his

Natural History

Pliny the Elder recorded this anecdote along with two others.

Zeuxis, he wrote, painted his grapes as part of a competition

with Parrhasius and admitted defeat when he asked Parrhasius to

pull the curtain in front of his painting, only to be told that

the curtain

was the painting. Gifford notes the second

story: "Zeuxis subsequently painted a child carrying grapes and

when birds flew to the fruit with the same frankness as before,

he strode up to the picture in anger with it and said, 'I have

painted the grapes better than the child, as if I had made a

success of that as well, the birds would inevitably have been

afraid of it'" (35.36). Clearly this is the source of Bloom's

thoughts about an unnamed boy: "

Would birds come then and

peck like the boy with the basket of fruit but he said no

because they ought to have been afraid of the boy."

The folds of Joyce's sentences contain one final allusion,

though this one does not figure in Bloom's consciousness. He

thinks, "

Apollo that was," mixing Zeuxis up with Apelles,

another Greek painter famed for realism, and mixing the man

Apelles up with the god Apollo. These minor mistakes would be

unremarkable were it not for a certain tongue-twisting rhyme

that uses both names. Slote cites Fritz Senn's observation that,

in a 15 September 1935 letter to his daughter Lucia, Joyce

referred to some doggerel lines familiar to Italian children:

Apelle, figlio di Apollo,

Fece una palla di pelle di pollo,

E tutti i pesci vennero a galla

Per mangiare la palla di pelle di pollo

Fatta da Apelle, figlio di Apollo.

(Apelle, the son of Apollo,

Made a ball of chicken skin

And all the fish came to the surface

To eat the ball of chicken skin,

Made by Apelle, the son of Apollo.)

Here the reader's hunt for relevant contexts trails off into

delightfully silly wordplay that Joyce could hardly have

expected English speakers to know and that does not come close

to commenting on the cult of the Sacred Heart (or anything

else in Ulysses, for that matter), though it does

continue Shakespeare's theme of animals pecking at flesh. Some

of his allusions, it seems, are games that the author is

playing only with himself, in chains of verbal, visual, and

conceptual association that the reader can scarcely begin to

follow. A spectacularly accelerating version of the children's

rhyme can be heard in the video displayed here.