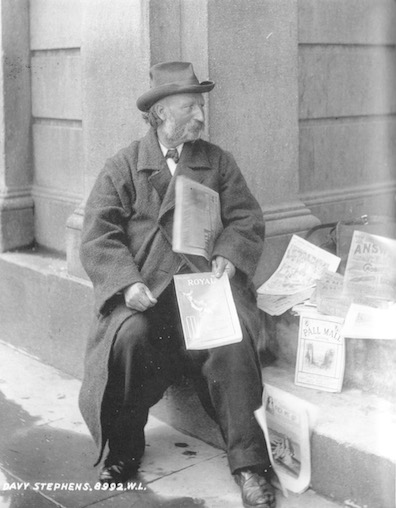

Vivien Igoe, who lists Stephens' birth date definitively as

1845, reports that he "started work aged six, selling copies

of Saunder's Newsletter to support his widowed mother.

For 60 years he operated from the steps of the railway station

at Kingstown (now Dún Laoghaire)." This location allowed him

quite literally to corner a major news market: nearly everyone

who traveled between Dublin and London took the mailboats,

connecting by train at either end. Cyril Pearl quotes

Stephens' claim to have sold papers to "monarchs, princes,

potentates, viceroys, all grades of the aristocracy, Lord

Chancellors, Prime Ministers, Commanders-in-Chief, Cardinals,

Archbishops . . . artists, authors, jockeys, prizefighters,

aeronauts, tight and slack rope-walkers, and dancers . . . and

'long' and 'short drop' hangmen" (Dublin in Bloomtime, 49).

The Emperor of Brazil, he notes, offered him the position of

Court Jester.

The Amazonian poobah's offer suggests that Stephens'

energetic hobnobbing with the high and mighty involved more

than a little condescension on their part, but he met them

halfway, recouping whatever scraps of personal dignity they

surrendered. In the best Dublin tradition of flamboyant

self-promotion, Stephens cultivated an image of closeness to

power, styling himself the Prince of the News Vendors, or the

King of the Newsboys. Many people joined the game by

addressing him as Sir Davy. Joyce's phrase "a king's

courier" alludes to Stephens' amicable interactions with

King Edward VII when he

came to Ireland in 1903, reprising earlier conversations when

Albert Edward had visited as Prince of Wales. The

autobiography that he published in 1903 records that Queen

Victoria gave him a sovereign on one of her visits; he

"loyally" kept it "mounted in a gold clasp ready for

inspection" and pinned it to his coat "on special occasions."

Many socially prominent persons besides Their Majesties seem

to have embraced Davy Stephens. Pearl observes that Lord

Northcliffe, who came to Ireland for the Gordon-Bennett Cup,

"invited Davy to accompany him in his car, and when someone

occupied Davy's stand during one of his regular attendances at

the English Derby, Michael Davitt raised the matter in the

House of Commons" (49-50). A prominent Irish MP, in other

words, intervened in Parliament to protect Stephens' de facto

monopoly on news vending in Kingstown. Pearl adds that "Davy's

activities were reported regularly in the Irish Society

and Social Review. A paragraph in the issue of 31st

October 1903 reads: 'Davy had a great shake hands from Mr John

Morley the other day. Davy congratulated him on the life of Gladstone, and presented

him with a copy of his own life, just published. Mr Morley

said he would read it carefully, and perhaps he might see a

review of it in one of the greatest of London's dailies'"

(50).

This autobiography, The Life and Times of Davy Stephens:

The Renowned Kingstown Newsman, took comical

self-aggrandizement to an admirably high pitch: "His exterior

is peculiar but prepossessing. Standing a little below the

usual height for the proverbial Irishman [Joyce calls him "minute"],

this point is quickly lost sight of in a deep well of wit, not

yet completely sounded, beaming forth in his eyes. No one can

say whether it is in the merry glance of his eye or in the

quick repartee that issues from his lips, never for a moment

sealed, that Davy's fortune lies. The corners of his mouth are

turned up in a perpetual smile which his clean shaven chin

tends to emphasise."

In a characterization that Joyce may well have appreciated,

Stephens noted that "His hair hangs down over his shoulders in

long strings, reminding one of that of Ulysses when tossed by

the sea at the feet of the charming Nausicaa, and the fresh

breezes of the Channel have reduced his complexion to a

compromise between red and brown. In a black frieze overcoat and

a soft Trilby hat ["

a large capecoat, a small felt hat"]

he braves the cross-Channel gales in winter as readily as he

broils beneath the portico of the railway station when the

temperature is only 88 degrees in the shade. Atmospheric

variations seemingly exert no influence on the perfect

constitution of Davy. The scent of the briny and the glint of

the sunshine are alike to him. Add to these particulars a fine

rich brogue and the man is complete."

The Thom's records suggest that, near the end of his

long life, Stephens forsook the rigors of his outdoor post for

a more sedentary life. In 1911, when he would have been nearly

70 years old, he was living at 33 Upper George's Street in

Kingstown and running a stationery business.