In part 5 of A Portrait of the Artist, Cranly asks

Stephen, "was your father what is called well-to-do? I mean

when you were growing up?" When Stephen says yes, Cranly asks,

"What was he?" and Stephen reels off an adventurous and

ultimately disreputable vita: "A medical student, an oarsman,

a tenor, an amateur actor, a shouting politician, a small

landlord, a small investor, a drinker, a good fellow, a

storyteller, somebody's secretary, something in a distillery,

a taxgatherer, a bankrupt and at present a praiser of his own

past." John Joyce inherited family money in Cork and steadily

lost every penny of it after moving to Dublin.

For the rest of the family, the man's inability to preserve

wealth and his heavy consumption of alcohol meant growing

poverty and the loss of a stable, comforting home. But as the

eldest son of a proud patriarch Jim was privileged, and the

good education he received gave him the tools to conceive of

himself as something other than a chip off the old block. It

is true that he largely retraced his father's path of

alcoholic excess and financial imprudence: in 1904 he wrote to

Nora Barnacle, "How could I like the idea of home? My home was

simply a middle-class affair ruined by spendthrift habits

which I have inherited." In fiction, however, he found a way

to surpass his father's prodigious capacity for entertainment.

Bloom alludes to this talent in Eumaeus by calling

Simon "A gifted man...in more respects than one and a born

raconteur if ever there was one." In

Calypso he thinks of Simon's talent for mimicry,

recalling his impersonation of Larry O'Rourke: "Simon

Dedalus takes him off to a tee with his eyes screwed up.

Do you know what I'm going to tell you? What's that, Mr

O'Rourke? Do you know what? The Russians, they'd only be an

eight o'clock breakfast for the Japanese." Readers of A

Portrait of the Artist will recall also his

magnificently acerbic contempt for the clergy and his worship

of Charles Stewart Parnell.

John Joyce was funny––socially assured, acidly irreverent,

witty––and his son remembered and used some of his lines.

Readers of the novel get an early taste of this wit when the

men in the funeral party contemplate the changing weather and

Simon remarks, "It's as uncertain as a child's bottom." Bloom

thinks of another remark in Lestrygonians as he

contemplates Parnell's brother John Howard Parnell: "Simon

Dedalus said when they put him in parliament that Parnell

would come back from the grave and lead him out of the House

of Commons by the arm." The best mot is given to Joe Hynes in

Cyclops. Ellmann recounts its genesis:

John Joyce, fearsome and jovial by turns, kept the

family's life from being either comfortable or tedious. In his

better moods he was their comic: at breakfast one morning, for

example, he read from the Freeman's Journal the

obituary notice of a friend, Mrs. Cassidy. May Joyce was

shocked and cried out, 'Oh! Don't tell me that Mrs. Cassidy is

dead.' 'Well, I don't quite know about that,' replied John

Joyce, eyeing his wife solemnly through his monocle, 'but someone

has taken the liberty of burying her.' James burst into

laughter, repeated the joke later to his schoolmates, and

still later to the readers of Ulysses.

When not in his better moods, John Joyce lapsed from charming

wit into savage invective. The saying "street angel, house

devil" might have been coined to describe this man, who was one

thing to his friends and something more complicated and

undependable to his family. In

Hades Simon displays love

for his dead wife: "— Her grave is over there, Jack, Mr

Dedalus said. I'll soon be stretched beside her. Let Him take me

whenever He likes. / Breaking down, he began to weep to himself

quietly, stumbling a little in his walk." But before she died

John made May's life miserable.

Wandering Rocks evokes

the man's mixture of affection and brutality when Dilly Dedalus,

acting as agent for her near-starving sisters, confronts Simon

outside the auction house where he has gone to sell furnishings

from the house. After enduring his demands to "Stand up

straight, girl," she presses her case:

— Did you get

any money? Dilly asked.

— Where would I get money?

Mr Dedalus said. There is no-one in Dublin would lend me

fourpence.

— You got some, Dilly

said, looking in his eyes.

— How do you know that? Mr

Dedalus asked, his tongue in his cheek....

— I know you did, Dilly

answered. Were you in the Scotch house now?

— I was not, then, Mr

Dedalus said, smiling. Was it the little nuns taught you to be

so saucy? Here.

He handed her a shilling.

— See if you can do

anything with that, he said.

— I suppose you got five,

Dilly said. Give me more than that.

— Wait awhile, Mr Dedalus

said threateningly. You're like the rest of them, are you? An

insolent pack of little bitches since your poor mother died.

But wait awhile. You'll all get a short shrift and a long day

from me. Low blackguardism! I'm going to get rid of you.

Wouldn't care if I was stretched out stiff. He's dead. The man

upstairs is dead.

He left her and walked on.

Dilly followed quickly and pulled his coat.

— Well, what is it? he

said, stopping....

— You got more than that,

father, Dilly said.

— I'm going to show you a

little trick, Mr Dedalus said. I'll leave you all where Jesus

left the jews. Look, there's all I have. I got two shillings

from Jack Power and I spent twopence for a shave for the

funeral.

He drew forth a handful of copper coins, nervously.

— Can't you look for some

money somewhere? Dilly said.

Mr Dedalus thought and nodded.

— I will, he said gravely.

I looked all along the gutter in O'Connell street. I'll try

this one now.

— You're very funny, Dilly

said, grinning.

— Here, Mr Dedalus said,

handing her two pennies. Get a glass of milk for yourself and

a bun or a something. I'll be home shortly.

This is one of two long cameos of Simon in

Ulysses. The

other comes in the next chapter when he sings the beautiful

M'appari

aria from Flotow's opera

Martha. The prose of

Sirens

lyrically presents the rapt attention of the listeners in

the Ormond bar: "Braintipped, cheek touched with flame, they

listened feeling that flow endearing flow over skin limbs human

heart soul spine." Their excitement mounts as the song nears a

climax presented in powerfully sexual language, and Simon

receives a thunderous round of applause. In

Penelope

Molly does not seem to like the man ("

such a criticiser,"

"

always turning up half screwed"), but she appreciates

his gift for natural, unforced singing. John Joyce sang in many

amateur concerts and was thought to have one of the finest tenor

voices in Ireland. His son James inherited at least some of his

gift.

Another way that the elder Joyce figures in Ulysses

is through the company he kept. The novel would be far less

richly mimetic without the social presence of men like Richard

John Thornton (the Tom Kernan of Hades), Tom Devin

(the Jack Power of Hades), Matthew Kane (the prime

inspiration for the Martin Cunningham of Hades and Cyclops),

Reuben J. Dodd (spotted in Hades), Mick Hart (the

Lenehan of Aeolus, Wandering Rocks, Sirens,

Cyclops, and Oxen of the Sun), "Long" John

Clancy (the Long John Fanning of Wandering Rocks),

Christopher Dollard (probably the model for the Ben Dollard of

Wandering Rocks and Sirens), George Lidwell (Sirens),

Alf Bergan (Cyclops), and Timothy Harrington (briefly

featured in Circe). These friends and political

associates of John Stanislaus greatly assist the book's

portrayal of Dublin as a warmly homosocial place, full of

drink, music, jokes, stories, and easy conversation.

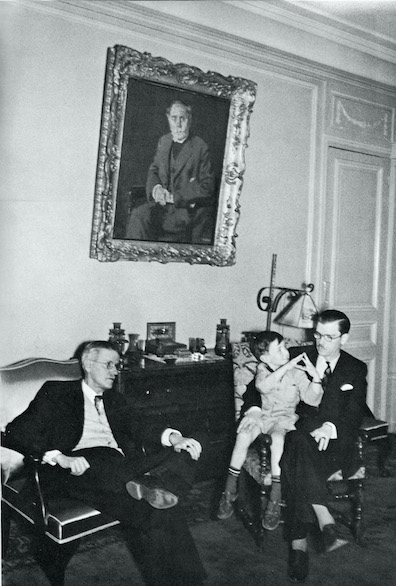

For readers who want to know more about Joyce's brilliant,

irascible, and complicated father, the biography John

Stanislaus Joyce (1998), by John Wyse Jackson and Peter

Costello, is recommended reading.