After six relatively placid chapters (Nestor has

shouting schoolboys, Hades some clattering

horsedrawn carriages), Aeolus plunges the reader

into the "THE HEART OF THE HIBERNIAN METROPOLIS": lower

Sackville Street and adjoining thoroughfares, where dozens of

"clanging" trams are noisily converging and departing,

clanking presses are churning out miles of newsprint, mail

cars are lining up before the General Post Office to

receive flung sacks of mail, barrels of porter are

"dullthudding" out of a warehouse and rolling onto a barge, a

conductor is shouting out directions, and bootblacks are

drumming up business. In this cacophonous bustle, two

impressions compete: Ireland does have a city to rival other

great European capitals; but far from being purely

"Hibernian," this is a conspicuously imperial capital.

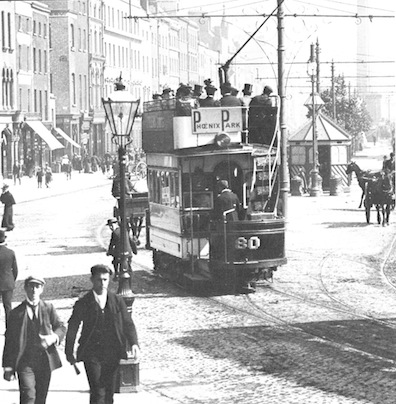

Joyce begins his cameo portrait of the metropolis with the

urban tram system that in 1904 was a source of great civic

pride. Over the preceding three decades tramlines had been

laid throughout greater Dublin, and by 1901 all the lines were

electrified and sported a fleet of mostly double-decker

electric trams. Bloom's repeated musings about the benefits of

running "a tramline from the parkgate to the quays" with

cattle "trucks" to avoid having to drive the animals through

the streets, and running a "line out to the cemetery gates"

with "municipal funeral trams like they have in Milan" (Hades)

reflects the spirit of civic improvement with which Dubliners

greeted an urban transportation system that in 1904 was

perhaps the best in Europe.

In Dublin in Bloomtime, Cyril Pearl quotes Tom

Kettle, "the brilliant young writer who was killed in World

War I," to the effect that "The tramcar is the social

confessional of Dublin. Sixpence prudently spent on fares will

provide you with a liberal education" (17-18). That sense of

expansive cosmopolitan communication appears in Joyce's next

vignette, the activity surrounding "the general post

office." The letters, cards, and parcels in the

flung sacks are bound "for local, provincial, British

and overseas delivery," and delivery to Britain, at

least, was quite swift. Twice a day mailboats promptly left the

enclosed harbor at Kingstown bound

for Holyhead in Wales, after receiving mail delivered by

express trains from Dublin. Other trains quickly shuttled the

mail from Holyhead to London.

But as the title of that second section, "THE WEARER

OF THE CROWN," proclaims, the "mailcars"

were the property of "His Majesty," "E.R.,"

Rex Edward VII, and every part of the efficient

system from "North Prince's street" to

Kingstown harbor existed to facilitate communication between

the two imperial capitals of Dublin and London. "Nelson's

pillar," an immense granite Doric column topped with a

heroic statue of Britain's most brilliantly successful naval leader, was erected in

Dublin in 1808, 35 years before the British got around to

building a similar one in Trafalgar Square in London. Dublin

has always been an imperial city (it was founded by Vikings),

and in the paragraphs that begin Aeolus one can hear

Joyce's recognition of the tension between aspiring to be one

of the great cities of Europe and knowing that it is one of

the key cities in the British empire.