As far as I know there are no photographs from the top of the

pillar that show the churches that Stephen mentions. But all

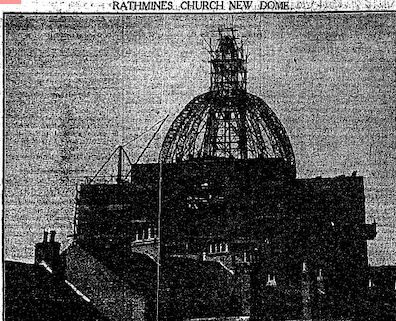

three are still standing. "Rathmines' blue dome" is a

church called Our Lady of Refuge (more fully, Church of Mary

Immaculate, Refuge of Sinners) in the suburb of Rathmines,

just beyond the Grand Canal

about three kilometers south of the pillar. The blue

appearance (many observers would have called it green) came

from a large oxidized copper dome. A catastrophic fire

destroyed the church in 1920 and the entire heavy dome smashed

down through its supports, but insurance money enabled quick

rebuilding. The beautiful new dome, completed in 1923, is

taller and more elaborate than its predecessor, but it too was

designed to weather to a blue-green hue, and it continues to

provide a striking visual landmark.

"Adam and Eve's," known more formally as the Church of

the Immaculate Conception of Our Lady, is an old Franciscan

church that figures prominently in Finnegans Wake:

"riverrun, past Eve and Adam's, from swerve of shore to bend

of bay." These opening words evoke the water flowing past

Merchant's Quay on the south bank of the Liffey. The church

lies just off that street, slightly more than a kilometer

west-southwest of the pillar. It too has a blue-green dome,

but Stephen does not mention that fact.

The last church he thinks of, "saint Laurence O'Toole's,"

is

a Gothic Revival limestone structure built in the 1840s and

50s several blocks north of what in Joyce's time were working

docklands on the Liffey, and about one and a half kilometers

east-northeast of the pillar. Its majestic four-stage tower

and spire, at the entrance to the nave, command views in the

area and were said to be the last landmark seen by emigrants

leaving Ireland from the North Wall.

To see these three churches at various points on the skyline

(south, west-southwest, east-northeast), Anne and Flo must be

walking around the viewing platform—a neat trick of suggesting

movement non-narratively. But Stephen may also be subtly

weaving a political thread into the story. Two of the churches

would have carried patriotic associations for any Irish

nationalist. Lorcán Ua Tuathail, later "saint Laurence

O'Toole," was a 12th century monk who became the first

Irishman elected Archbishop of Dublin, a town ruled by Danes

and Norwegians. He was canonized by Pope Honorius III in 1225,

and later became Dublin's patron saint because, as archbishop

at the time of the Norman invasions, he protected the city's

inhabitants, using the respect and trust he inspired in all

who met him to obtain clemency from the bloodthirsty knights

besieging his city.

"Adam and Eve's" gained its colloquial name because,

when Catholic religious observances were prohibited by penal

laws in the 18th and early 19th centuries, the Franciscans

secretly held Mass for worshipers who entered through the Adam

and Eve Tavern next door to the church. Joyce mentions the

church's services in Cyclops, when the narrator

despises Bob Doran for "talking against the Catholic religion,

and he serving mass in Adam and Eve’s when he was young

with his eyes shut, who wrote the new testament, and the old

testament." Ithaca alludes specifically to the

surreptitious masses of earlier times when Stephen and Bloom

find a spiritual bond in belonging to despised faith

communities: "their dispersal, persecution, survival and

revival: the isolation of their synagogical and

ecclesiastical rites in ghetto (S. Mary’s Abbey) and

masshouse (Adam and Eve’s tavern): the proscription of

their national costumes in penal laws and jewish dress acts:

the restoration in Chanah David of Zion and the possibility of

Irish political autonomy or devolution."

As for the Rathmines church, the question of "political

autonomy" (republican independence) or "devolution" (greater

self-rule within the British empire) that dominated Irish

political discourse in the early 20th century impacted that

sacred space dramatically in January 1920. For some time,

members of the Dublin IRA, assisted by a church official who

belonged to "A" Company, had slept in the church whenever

police came looking for them at their houses (making it, as

Frank McNally pointed out in an Irish Times column a

couple of years ago, a Refuge of Shinners). When the great

fire broke out, it became difficult to conceal the fact that

"A" Company had also been storing large quantities of weapons

and ammunition in the church's vaults.

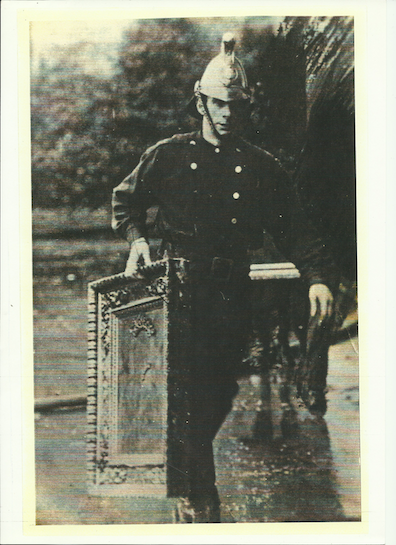

An article dated 5 August 2013 on the Dublin history blog Come

Here to Me!, written by Donal and indebted to a 2012

book by Las Fallon titled Dublin Fire Brigade and the

Irish Revolution, describes the chaotic scene that

resulted: firemen furiously pumping water from the Grand

Canal, the church's dome threatening to come crashing down,

and republican soldiers rushing into the burning building to

retrieve munitions. After the fire was extinguished, there was

fear that British authorities might find remaining arms during

clean-up operations, so IRA man Michael Lynch (according to

testimony he gave to the Bureau of Military History) went to

talk to DFB Captain John Myers, whom he knew to be "a very

fine fellow and, from the national point of view, thoroughly

sound and reliable in every way." Myers assured Lynch that no

one would ever know about any guns found in the rubble, and he

was true to his word.

This history, only recently compiled, may well be dismissed

as something that Joyce, in his distant continental exile,

could not possibly have heard about. But on this, as on so

many other points, Ulysses gives its readers just

enough telling details to make them question their

incredulity. In Circe, when Bloom is sentenced to

death by the Inquisition, the sentence is carried out by the

Dublin Fire Brigade, led by Myers:

THE FIRE BRIGADE

Pflaap!

BROTHER BUZZ

(Invests Bloom in a yellow habit

with embroidery of painted flames and high pointed hat. He

places a bag of gunpowder round his neck and hands him

over to the civil power, saying.) Forgive him his

trespasses.

(Lieutenant Myers of the

Dublin Fire Brigade by general request sets fire to Bloom.

Lamentations.)

THE CITIZEN

Thank heaven!

BLOOM

(In a seamless garment marked I.

H. S. stands upright amid phoenix flames.) Weep not for

me, O daughters of Erin.

(He exhibits to Dublin reporters traces

of burning. The daughters of Erin, in black garments,

with large prayerbooks and long lighted candles in their

hands, kneel down and pray.)

Catholic church services, a stash of gunpowder, Dublin Fire

Brigade troops, and John Myers: the coalescence of these

details must, at a minimum, be deemed a very strange

coincidence. If Joyce did intend for his three churches to

carry nationalist associations, he could not have chosen a

more opportune vantage than Nelson's Pillar, a symbol of

British military might towering over a street identified with

Ireland's foremost promoter of

Catholic rights. O'Connell's political career

represented one long assault on the penal laws of Nelson's

era. His statue at the

bottom of the street (unveiled in 1882) challenged Nelson's

statue (erected in 1808) in front of the Post Office. To this

nationalist protest in bronze, Joyce arguably added two in

print. Stephen's three "different churches" speak back to the

tower from which they are viewed, and when Florence and Anne

"pull up their skirts" and expose themselves to the admiral

they cast a

spell to drive him out of Ireland.