Crawford's caution reflects the fact, noted by Slote,

Mamigonian, and Turner, that the Archbishop of Dublin, William

Walsh, had for some time been in a "contentious relationship"

with the Freeman's Journal. As editor of the

newspaper, Crawford does not want Stephen to give further

cause for offense. And for a moment the story appears to be

moving in a chaste direction: the two women simply do not want

to soil their dresses with the grime of the viewing platform,

so they pull them up far enough that they can instead sit on

their petticoats.

But in the late Victorian and early Edwardian era, showing

even small fringes of such undergarments was regarded as

scandalous self-exposure, and twice already in the novel

petticoats have carried lewd implications––first in Telemachus

when Mulligan sings about Mary Ann "hising up her

petticoats" to pee like a man, and then in Proteus

when Stephen imagines the moving fronds of seaweed as women, "hising

up their petticoats," "upturning coy silver fronds,"

"Weary too in sight of lovers, lascivious men, a

naked woman shining in her courts." These two liftings

of petticoats both imply sexually arousing display, so when

Stephen's two vestals "pull up their skirts" and display their

petticoats, one may suppose that a similar erotic charge may

be involved.

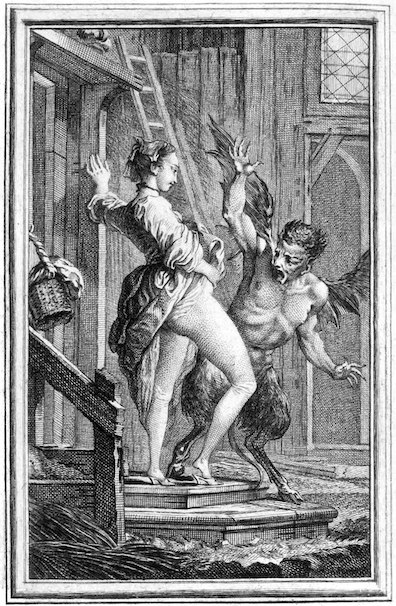

In a personal communication, Alexander Medvedev suggests the

relevance of the ancient iconographic tradition of anasyrma,

in which a figure is depicted pulling aside garments to

display his or her private parts––perhaps most famously in the

statues of the Aphrodite Kallipygos, or Venus of the

Beatiful Buttocks, referenced in Circe. Various

explanations have been offered for the social function of such

aesthetic representations in ancient Greece. At one extreme,

simple mocking lewdness may have been involved. But there is

evidence that the display may have had religious ritual

significance: the Eleusinian mysteries associated with the

worship of Dionysus and Demeter involved lightheared lifting

of skirts by old women. There is also evidence that apotropaic

magic was involved. Various ancient, medieval, and early

modern writers (Pliny the Elder, Moses Maimonides, Jean La

Fontaine) attributed magical powers to women who exposed their

genitals: storms could be averted, crop pests dispelled, and

demons driven away.

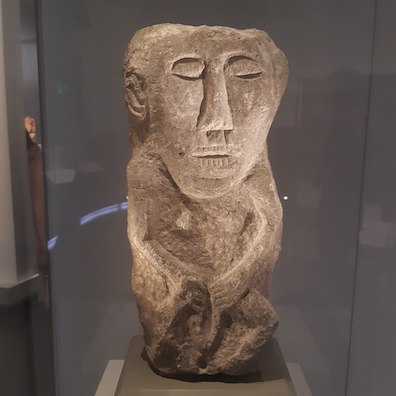

Medvedev reflects that similar apotropaic powers have been

attributed to the medieval stone carvings known as sheela na

gigs––naked women with large vulvas that are often held gaping

open. These grotesque medieval carvings can be found on

cathedrals, castles, and other buildings in a number of

European countries, but by far the greatest number of

surviving ones are in Ireland––124, according to Jack

Roberts's The Sheela-na-gigs of Ireland, An Illustrated

Map & Guide (2009). They are often described as old

women, hags, crones. People have interpreted their signficance

quite predictably as vestiges of an ancient goddess religion,

or as fertility icons meant to help women approaching the

terror of labor, or as warnings against lust, but another

theory is that these figures were amulets against evil.

Although this explanation is less obvious, more evidence

supports it, as some of the Irish sheelas have been called

Evil Eye Stones. One of these is in a ruined abbey on the

grounds of Malahide Castle. In an 11

September 2003 article in the Irish Independent,

Hubert Murphy notes that "Eagle-eyed visitors can catch a

glimpse of the Sheela na Gig, also known as Devil Stone, the

Evil Eye stone, the Idol, the Witch or the Hag of the Castle,

high up on the North-East wall of Malahide Abbey."

Stephen's very ordinary old women were suggested by the two

he saw on Sandymount Strand. He gives them fictional names, a

Dublin address, simple appetites, and common ailments, and he

presents them as impoverished local tourists who have saved up

coins to pay the entrance fee and take in the great views from

the top of Nelson's pillar. But some symbolic significance is

attached to them when he calls them "vestals," and when

Professor MacHugh follows his lead by referring to them as "Vestal

virgins." The Vestal Virgins of ancient Rome were

priestesses of the goddess Vesta invested with unusual rights,

powers, and privileges. People regarded them with awe and

assumed that they possessed supernatural abilities. They could

free condemned men on their way to execution simply by

touching them or being seen. In his Natural History,

Pliny the Elder affirms that a certain prayer uttered by the

Vestals could "arrest the flight of runaway slaves...provided

they have not gone beyond the precincts of the City." It was

believed that, as long as their sexual barriers remained

intact, the walls of Rome would also. They held sovereign

power over themselves and even their money, answering only to

the pontifex maximus.

The symbolic presence of these guardians of Rome in Stephen's

aged virgins may well figure in the action that he has them

perform: exposing themselves to the great British admiral. One

need not assume that Florence MacCabe and Anne Kearns uncover

their genitalia in Nelson's presence, or even that they reveal

more than the bottom half of their petticoats. All that

matters is that, in their relatively scandalous state of

deshabille, they are seen "peering up at the statue of the

onehandled adulterer" while sensuously sucking on plums and

spitting out stones. In this condition of sexual

self-exposure, the traditions of anasyrma statues and

Sheela carvings may suggest, not a desire to copulate with the

conqueror, but rather a defiance of the empire he represents

and an apotropaic charm guarding Ireland against its evil

presence. Florence and Anne must probably be supposed innocent

of any such defiant intent. But in a chapter littered with

symbolic analogues for Ireland's imperial degradation,

Stephen's little tale about them may well perform that

function.

In the episode's final paragraphs Stephen explicitly links

his "Parable of the Plums" with "A Pisgah

Sight of Palestine"––a biblical vision of the

"promised land" which God has reserved for his people. Through

this linkage, it becomes clear that the most potent analogue

of Irish liberation in Aeolus––Moses's defiance of the

Egyptian Pharaoh––shares a deep symbolic connection with the

two old women exposing themselves. Looking down from a high

place, Moses, Florence, and Anne all see the nation which

could be.