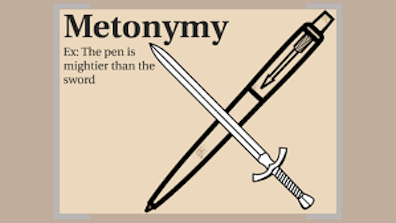

Metonymy

(muh-TON-uh-mee, from Greek

meta- = changing places with

+

onoma = name) is "substitute naming." It resembles

metaphor

in that one thing stands for another by simple power of

evocation, without the need for explicit connectives such as

"like" or "as." A metonym, however, suggests its counterpart

merely by virtue of being commonly associated with it. To cite a

few American examples, the White House refers to the executive

branch of the government, stuffed shirts are pompous people, and

suits are business executives. The line between metonymy and

synecdoche,

which uses a part to stand for the whole, can sometimes be very

faint.

Richard Nordquist (thoughtco.com) quotes from Hugh Bredin's

Poetics

Today (1984) a sentence that captures the difference

between metonymy and metaphor: "Metaphor creates the relation

between its objects while metonymy presupposes that

relationship." From Murray Knowles and Rosamund Moon's

Introducing

Metaphor (2006) Nordquist cites another excellent

distinction: "Metonymy and metaphor also have fundamentally

different functions. Metonymy is about

referring: a

method of naming or identifying something by mentioning

something else which is a component part or symbolically linked.

In contrast, a metaphor is about understanding and

interpretation: it is a means to understand or explain one

phenomenon by describing it in terms of another."

When the metonym's work of reference is accomplished, no further

thinking is needed, a fact which can be seen in Joyce's

headline, "

THE CROZIER AND THE PEN." It refers back to

the publisher of the newspaper, who has just walked through the

office, and forward to the archbishop, who is mentioned in the

first sentence of the new section: "— His grace phoned down

twice this morning, Red Murray said gravely." The crozier is a

sheephook-like staff carried by bishops and archbishops,

symbolic of their pastoral care. Like the pen, it can be used to

readily refer to a profession, without prompting any further

thought.

Stuart

Gilbert identifies these devices as "concrete

synechdoche," which seems wrong since a crozier is not really

part of a bishop, nor a pen of a journalist. For metonymy he

cites the earlier headline, "THE WEARER OF THE CROWN."

That is not quite right either: the crown may serve as a

metonym for the monarch, but in this case Joyce avoids the

trope by referring explicitly to the person who wears it, so

no figure of speech is really involved. Robert

Seidman repeats Gilbert's mistake about this phrase, but

he correctly identifies "the crozier and the pen" as metonymy.

He also observes that the use of a pen to symbolize journalism

is repeated later in Aeolus: "That was a pen,"

Myles Crawford says of Ignatius Gallaher.

Shortly after this, the editor uses similar metonyms for

journalists and lawyers: "Press and the bar!" Newspaper

reporters are readily associated with the printing press, and

lawyers with the bar. In the sentence that follows, Crawford

undoes the metonymy in the same way that "the wearer of the

crown" did: "Where have you a man now at the bar like

those fellows, like Whiteside, like Isaac Butt, like

silvertongued O'Hagan. Eh?"