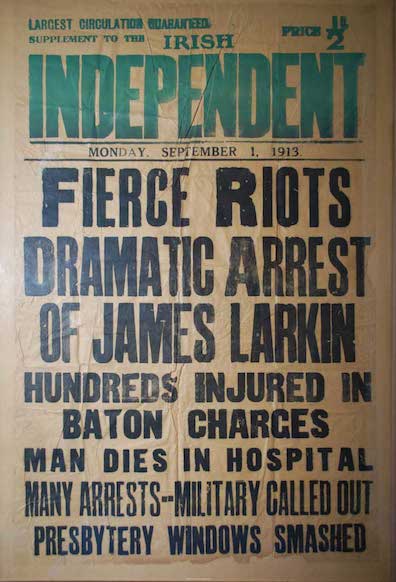

All-caps headlines in The Irish Independent, 1

September 1913.

Source: www.rte.ie.

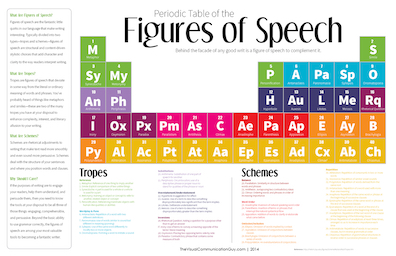

Source: www.visualcapitalist.com.

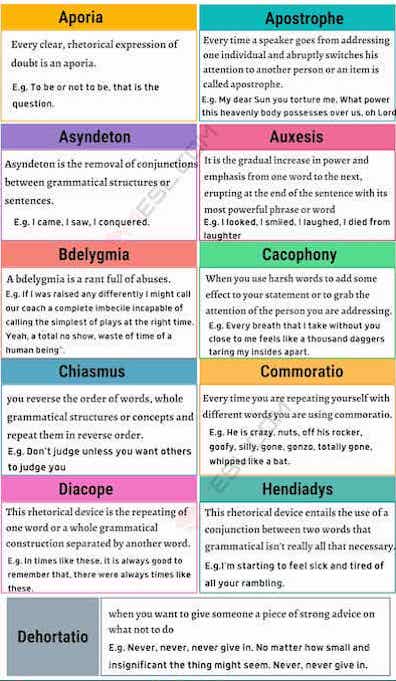

Source: www.visualcapitalist.com.

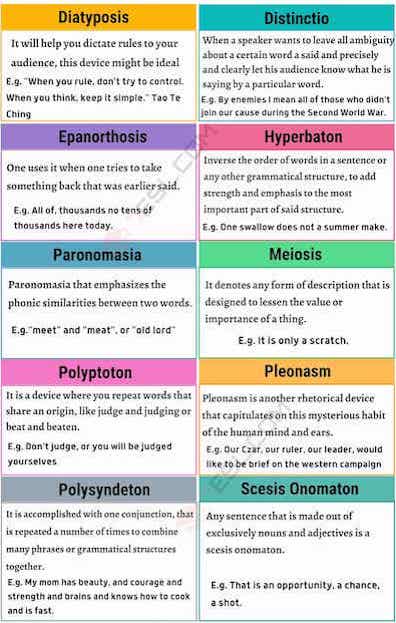

Source: 7esl.com.

In the heart

Figure of speech: many of my notes for Aeolus

will start with this heading. Joyce's chapter parodies the

format of a newspaper, with all-caps headlines introducing

short, punchy chunks of text. But in both of his schemas

he identified its "art" as rhetoric, the ancient study of

linguistic craft by which orators could catch their listeners'

attention, manipulate their emotions, and persuade them to the

rightness of a cause. In addition to three complete speeches

exemplifying Aristotle's three types of oratory, Joyce filled

his text with smaller-scale figures of speech: words and

phrases ordered by recognizable patterns of artful design. Of

the seemingly countless figures identified by ancient

theorists, most of them bearing Greek names, probably the most

familiar is metaphor, so it is fitting that Aeolus

should begin with one: "IN THE HEART" of a big city.

A metaphor (MET-uh-for or MET-uh-fuhr, from Greek meta-

= beyond, over + pherein = to bear, carry) means

"carrying over" the sense of one thing via another. The sense

being carried is sometimes called the "tenor" (meaning what is

held), and the thing holding it the "vehicle." Joyce's

vehicle, "heart," suggests the commercial center of Dublin

where the action of Aeolus is set. The tram hub at Nelson's

pillar in the opening section, the General Post Office

in the second section, the barrels of ale seen rolling out of

Prince's Stores in the third, and the offices of the Freeman's

Journal and the Evening Telegraph in

later sections, all are on or near lower Sackville

Street––the CBD, in today's parlance.

After the opening headline Joyce breathes life into his

metaphor by emphasizing the throbbing hum of activity in all

these places and suggesting that trams, newspapers, postal

services, and beer barrels all involve types of circulation.

On first hearing, though, the comparison seems old and tired,

a cliché. And this too probably figured in the artist's

intentions: "In the heart of the Hibernian metropolis" is

exactly the kind of stale, familiar metaphor that modern men

and women expect to encounter in newspaper headlines.

Stuart Gilbert was the first to comment (in James

Joyce's Ulysses) on the abundance of rhetorical figures

in Aeolus, no doubt alerted to them by Joyce himself.

He notes the resemblance to William Shakespeare: "The

thirty-two pages of this episode comprise a veritable

thesaurus of rhetorical devices and might, indeed, be adopted

as a text-book for students of the art of rhetoric. Professor

Bain has remarked that in the course of the plays 'Shakespeare

exemplifies nearly every rhetorical artifice known'" (172). In

support of his claim, Gilbert appends to the end of his

chapter on Aeolus a list of examples ("far from being

exhaustive") of many dozens of ancient rhetorical devices in

Joyce's text.

Professor Bain was right, and the reason that Shakespeare

wrote in rhetorical figures is not mysterious. In his day

rhetoric, one of the three arts comprising the medieval trivium,

was regarded as supremely useful in the conduct of everyday

life, so the humanist educators of early modern grammar

schools instructed boys in the use of such figures, and adult

writers like George Puttenham and John Lyly made careers out

of them. Where Joyce may have learned them is less obvious,

but the Jesuit ideal of a

Christian eloquentia perfecta sprang from humanist

roots and was taught in Jesuit schools from the 16th century

to the 20th, so it seems likely that Joyce gained his

introduction to rhetorical tropes in the same way that

Shakespeare did—in school.

In an appendix to the second edition of Gifford's Ulysses

Annotated Robert Seidman updated Gilbert's appendix,

adding still more figures of speech. "The earlier manuscript

drafts of Aeolus in The Little Review," he

notes, "suggest that Joyce added a great number of rhetorical

figures in his revisions, deliberately larding the chapter

with as many devices as possible." Identifying the figures in

Aeolus is a worthy task, then, but the work is by no

means straightforward. Rhetorical theorists often differed

from one another on the precise meaning of a term or used

different ones to describe the same linguistic effect, so many

of their terms overlap. Multiple and competing terms may apply

to a single sentence. And a writer of Joyce's caliber wants to

make his own kinds of effects, regardless of what some

theorists may say. Describing the rhetorical figures in Aeolus

is probably more art than science, then, but it does reveal a

lot of what is happening in Joyce's prose.

My notes on rhetorical figures are longer than Gilbert's and

Seidman's brief comments, but I generally follow paths laid

down by those two men. Sometimes, however, I disagree with one

or both, or add to their findings, or ignore claims that seem

weak, and I dispense with many terms (e.g., archaism, epigram,

neologism, Hibernicism, hapax legomenon) that have little to

do with the rhetorical tradition. No doubt many stones will be

left unturned here. In addition to the fact that there are

hundreds of terms to consider, Joyce sometimes uses a device

more than once. For example, in the present case Seidman does

not identify "in the heart of the Hibernian metropolis" as a

metaphor, but he does flag a later word, "Weathercocks,"

observing that "to Bloom, journalists are like the cocks that

top weathervanes." Gilbert neglects "heart" but mentions "steered

by an umbrella." Neither man mentions "The father

of scare journalism," which is still another metaphor.

Aristotle's Rhetoric, written in Greek, is available

in good English translations, as are Quintilian's

twelve-volume Latin Institutes of Oratory and the

earlier, anonymous Rhetorica ad Herennium, whose

fourth book describes many figures of speech. These works were

prized by humanist scholars of the early modern period and

inspired English handbooks like Henry Peacham's The Garden

of Eloquence and George Puttenham's The Arte of

English Poesie, both published in the late 1580s just as

Shakespeare was starting to write. Another important study of

the English Renaissance, published in 1657, was The

Mystery of Rhetoric Unveiled by John Smith, a pseudonym

used by John Sergeant. Many studies of rhetoric have been

published in the centuries since, and today countless websites

offer lists and discussions of figures of speech. In addition

to the published works mentioned above, my notes often cite

two websites that I find particularly useful: Gideon Burton's

Silva Rhetoricae (rhetoric.byu.edu) and Richard

Nordquist's pages on ThoughtCo. (www.thoughtco.com). For sheer

volume of terms, definitions, and examples, the list compiled

and openly edited at rhetfig.appspot.com/list is also worth

looking at.

This site offers notes on many figures of speech. Some of the

Greek terms below appear to have been coined by rhetoricians

writing in Latin, while others already existed in Greek

vocabulary. Most acquired Latin and English equivalents. To

minimize confusion I avoid Latin synonyms most of the time,

and English ones entirely. But I do often mention Greek

synonyms and near-synonyms, as can be seen on some of the

lines:

Allegory

Anacoenosis

Anadiplosis

Aporia, Latin dubitatio

Aposiopesis

Apostrophe

Anagram

Anaphora

Anthimeria

Anticlimax

Antithesis, antitheton

Antonomasia

Asyndeton

Catachresis, Latin abusio

Chiasmus, antimetabole

Ecphonesis, Latin exclamatio

Enthymeme

Epanalepsis

Epanorthosis, metanoia, Latin

correctio

Epimone, Latin perseverantia

Epiphonema

Epistrophe, epiphora,

antistrophe

Epizeuxis, palilogia, Latin

geminatio

Erotesis, erotema

Exergasia, Latin expolitio

Homoioteleuton

Hyperbaton, hysteron proteron,

anastrophe

Hyperbole

Hypophora

Hypotyposis, enargia

Irony

Litotes

Metaphor

Metaplasm (antisthecon, Latin

littera pro littera)

Metaplasm (apocope, syncope,

aphaeresis)

Metaplasm (diaeresis)

Metaplasm (metathesis)

Metonymy

Onomatopoeia

Oxymoron

Palindrome

Parabola

Paralepsis, apophasis

Parenthesis

Parody

Paronomasia

Periphrasis

Ploce

Polyptoton, paregmenon

Polysyndeton

Prolepsis

Prosopopoeia

Simile

Symploce

Synchoresis, paromologia,

procatalepsis

Synecdoche

Synonymia

Tapinosis

Tautologia, pleonasm

Zeugma, syllepsis

Readers who confront this paradox may have different ways of accounting for it. Did Joyce mean to suggest that even the most common and banal forms of human communication unconsciously employ rhetorical strategies of description and persuasion? Or was he self-consciously showing off his own learning and ingenuity? Did he admire speakers' ability to shape words for emotional effect, even when their artistry is tawdry? (While Dan Dawson's speech is being ridiculed Bloom thinks, "All very fine to jeer at it now in cold print but it goes down like hot cake that stuff.") Did he instead entertain suspicions like those of Plato, who viewed the original professional orators, the Sophists, as golden-tongued misleaders? (Professor MacHugh warns, "We mustn't be led away by words, by sounds of words.")