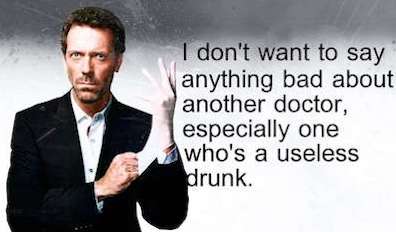

Figure of speech. Of Gerald Fitzgibbon's remarks

opposing the revival of the Irish language, Professor MacHugh

says that "It was the speech...of a finished orator, full of

courteous haughtiness and pouring in chastened diction I will

not say the vials of his wrath but pouring the proud man's

contumely upon the new movement." Saying that one will not say

something is one way of saying it. The rhetorical tradition

has a name for this ironic tactic: paralepsis. It

sometimes uses the term apophasis for the same

purpose.

Paralepsis

(par-uh-LEP-sis, from Greek

para- = beside +

leipein

= to leave), sometimes spelled paralipsis or paraleipsis, is

"leaving aside" something that one nevertheless mentions. Gideon

Burton (rhetoric.byu.edu) defines it as "Stating and drawing

attention to something in the very act of pretending to pass it

over. A kind of irony." As an example he quotes from the

"Breakfast" chapter of

Moby-Dick: "We will not speak of

all Queequeg's peculiarities here; how he eschewed coffee and

hot rolls, and applied his undivided attention to beefsteaks,

done rare." Richard Nordquist (thoughtco.com) cites another

lovely gustatory use by Tom Coates on Plasticbag.org: "Let's

pass swiftly over the vicar's predilection for cream cakes.

Let's not dwell on his fetish for Dolly Mixture. Let's not even

mention his rapidly increasing girth. No, no—let us instead turn

directly to his recent work on self-control and abstinence."

Among other examples, Nordquist cites the moment in

Julius

Caesar in which Mark Antony waves Caesar's will in front

of the plebeians, implying that they are beneficiaries but not

reading from the document.

Apophasis (uh-POF-uh-sis, from Greek

apo- = off +

phanai

= to speak) is "speaking off" or denying something. For

rhetoricians it can have the non-ironic meaning summarized by

Burton: "The rejection of several reasons why a thing should or

should not be done and affirming a single one, considered most

valid." But it can also mean, as Nordquist observes, "the

mention of something in disclaiming intention of mentioning

it––or pretending to deny what is really affirmed." In

The

Mystery of Rhetoric Unveiled,

John Smith defines it as "a

kind of Irony, whereby we deny that we say or doe that which we

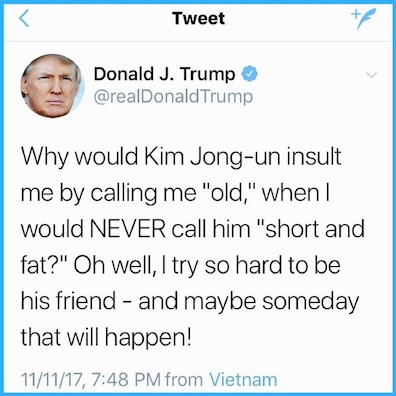

especially say or doe." Nordquist cites a slew of stinging uses

from the political arena. If apophasis differs from paralepsis

in any real way (I am not sure that it does), it would consist

in the use of outright denial to advance one's ironic attack: I

will

not blame my opponent for having done the

despicable thing that I have just insinuated he has done, or

hold against him the terrible failing of which he is clearly

possessed.

§ MacHugh's

use of one or the other of these rhetorical devices is

relatively mild. Describing the scorn that Fitzgibbon "poured"

on the Irish language movement, he calls it a principled

dislike ("the proud man's contumely") rather than

emotional intemperance ("the vials of his wrath"). He

borrows both expressions from famous works of literature. The

writer of the book of Revelation recalls "a great voice"

telling the seven angels to "pour out the vials of the wrath

of God upon the earth" (16:1), and in his "To be or not to be

soliloquy Hamlet speaks of "The oppressor's wrong, the proud

man's contumely" (3.1.70).