Figure of speech. Twice, Myles Crawford asks his

listeners a question which he proceeds to answer himself: "You

know how he made his mark? I'll tell you"; "Look at here. What

did Ignatius Gallaher do? I'll tell you." The rhetorical term

for such one-person Q&A is hypophora, a kind of

reasoning aloud that requires listeners to do nothing but

listen.

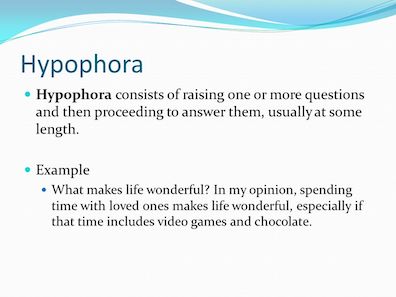

Hypophora (hie-PAH-for-uh, from Greek hypo- = under +

phora = carrying) has much in common with so-called

"rhetorical questions" like anacoenosis and erotesis.

Anacoenosis makes a show of soliciting listeners' opinions

while directing them toward a very limited range of correct

answers. Erotesis implies an answer so obvious that no

audience participation is needed. Hypophora too eliminates all

audience involvement, but it expands the range of possible

answers. The speaker responds to his own question with a

considered, and often quite lengthy, reply. (Sometimes the

answer is called anthypophora, in the same way that sung

responses in a church liturgy are called antiphons. The

ancient Greek rhetorician Gorgias uses the word anthypophora

in this sense, as does the English writer George

Puttenham.)

Richard Nordquist (thoughtco.com) offers a host of examples

from TV ads ("What's the best tuna? Chicken of the Sea"),

songs ("Oh, what did you see, my blue-eyed son? / Oh, what did

you see, my darling young one?..."), books ("Who wants to

become a writer? And why?..."), and speeches. One brief

example of oratorical hypophora may suffice here. In a 1970

commencement address, the poet Ogden Nash asked, "How are

we to survive? Solemnity is not the answer, any more than

witless and irresponsible frivolity is. I think our best

chance lies in humor, which in this case means a wry

acceptance of our predicament. We don't have to like it but we

can at least recognize its ridiculous aspects, one of which is

ourselves."

Neither Gilbert nor Seidman lists

hypophora among the rhetorical devices of Aeolus, but

it seems appropriate to the question that the newspaper editor

asks about the reporting of the Phoenix Park murders. Crawford

has a detailed story to tell and he wants to tell in his own

way, at length. But he introduces his lecture with a question:

"What did Ignatius Gallaher do?"