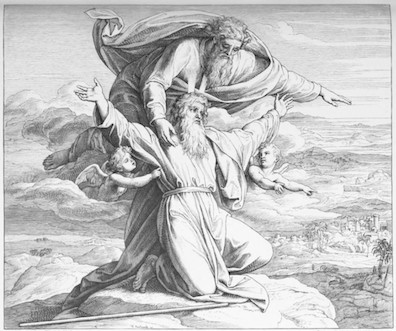

The Pentateuch concludes with the death of Moses:

And Moses went up from the plains of Moab unto the

mountain of Nebo, to the top of Pisgah, that is over against

Jericho. And the Lord shewed him all the land of Gilead, unto

Dan. And all Naphtali, and the land of Ephraim, and Manasseh,

and all the land of Judah, unto the utmost sea, And the south,

and the plain of the valley of Jericho, the city of palm

trees, unto Zoar. And the Lord said unto him, This is the land

which I sware unto Abraham, unto Isaac, and unto Jacob,

saying, I will give it unto thy seed: I have caused thee to

see it with thine eyes, but thou shalt not go over thither. So

Moses the servant of the Lord died there in the land of Moab,

according to the word of the Lord.

(Deuteronomy 34:1-5)

Pisgah, a Hebrew word meaning "summit" or "peak," refers to a

mountain ridge east of the Dead Sea, and to Mount Nebo within

that range. God takes Moses to the top of the peak, shows him

the Palestinian lands that he has promised to his chosen

people, and informs him that he will not be among them when

they end their 40 years of wandering and begin a new settled

life. Moses dies at the age of 120, and the Torah ends with an

assessment of the prophet's importance: "And there arose not a

prophet since in Israel like unto Moses, whom the Lord knew

face to face. In all the signs and the wonders, which the Lord

sent him to do in the land of Egypt to Pharaoh, and to all his

servants, and to all his land, And in all that mighty hand,

and in all the great terror which Moses shewed in the sight of

all Israel" (34:10-12).

Aeolus has introduced a symbolic equivalence between

Ireland and Israel, and the stirring speech of John F. Taylor

recited by Professor MacHugh develops this analogy. The speech

advocates for "the revival of the Irish tongue" by imagining

what Moses would have said to Egyptians demanding, "Why

will you jews not accept our culture, our religion and our

language?" When Moses comes down from Sinai "bearing

in his arms the tables of the law, graven in the language of

the outlaw," he represents symbolically the political

aspirations of the people of Ireland and the artistic

aspirations of James Joyce, who was poised to put Ireland on

the cultural map by writing the epic of his race in a new kind

of language. Stephen's little story of two Irish women gazing

up at the statue of the English conqueror is a down payment on

the representation of ordinary Irish lives that would

eventually become Ulysses.

The spinsters' high station atop Nelson's pillar corresponds

to Moses's high vantage atop a mountain, and when they reach

the viewing platform the two women scan the geography of

Dublin for its prominent (and possibly

resistance-associated) Catholic churches, just as Moses

surveys the Palestinian lands in which his people will find

freedom and self-determination: "They see the roofs and argue

about where the different churches are: Rathmines' blue dome,

Adam and Eve's, saint Laurence O'Toole's." After they do this,

Florence and Anne settle themselves on their petticoats and

turn their gaze in a new direction, "peering up" at the statue

of Lord Nelson. This upward gaze has no precedent in

Deuteronomy 34, but it does have a possible explanation. By

lifting up their skirts and exposing themselves in a sexually

suggestive manner to the English admiral, the old women are performing a

certain kind of magical spell to cast out the evil

presence of the English.

If Joyce's "Parable" does imply apotropaic magic, then it may

also contain a second linkage with the biblical Pisgah. In a

personal communication, Alexander Medvedev points out that

Numbers 23 mentions Pisgah in connection with the casting of

spells. Chapters 22-24 of Numbers tell how Balak, the king of

Moab, three times asks the prophet Balaam to help him defeat

the Israelites by casting a curse on them. Each time, Balaam

privately consults God and comes back with the message that

God has decided to bless the Israelites, so a curse cannot

work. The second attempt takes place on Pisgah: "And he

brought him into the field of Zophim, to the top of Pisgah,

and built seven altars, and offered a bullock and a ram on

every altar" (23:14). This passage in the Hebrew Bible is much

less well known than Moses's "Pisgah Sight of Palestine,"

but it is extremely interesting that the peak also functions

as a place from which a curse may be cast to defeat a hated

enemy.

If one supposes that Joyce knew this second passage, then the

idea that Stephen's two spinsters may be performing apotropaic

magic on the English military becomes virtually certain. In

this case, Stephen's linkage of two alternate titles––Pisgah

Sight of Palestine, Parable of the Plums––would make perfect

sense. From the top of their tower, the two wise virgins are

surveying the promised land of an independent Ireland and

casting out the hated conqueror.