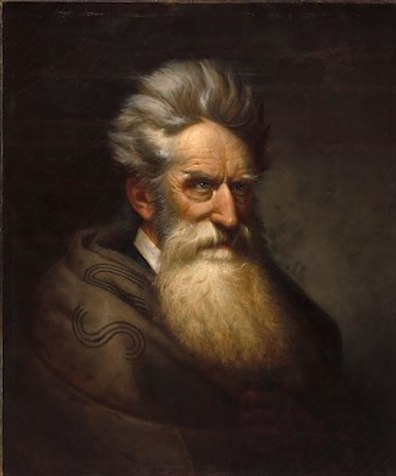

Brown was a fiery abolitionist from violence-torn Kansas who

led a raid on the U.S. federal armory and rifle factory at

Harpers Ferry, Virginia in October 1859. Impatient with the

pacifism of most abolitionists, he hoped to inspire a revolt

among slaves in Virginia and North Carolina, arming them with

long guns from the arsenal. The raid was briefly successful

but the insurrection did not spread far. Surrounded by local

farmers and captured two days later by federal troops under

Lt. Colonel Robert E. Lee, Brown was quickly charged with

treason (the first man in America to be so), convicted, and

hanged. Republican politicians disowned his violence, but many

Americans were either inspired or alarmed by his rash action.

It contributed to the South's decision to secede from the

Union in 1860, and it hardened the North's desire to end

slavery.

Northern soldiers, fond of singing as they marched, soon came

up with a revival-style folk anthem proclaiming the

righteousness of Brown's anti-slavery crusade. Countless

variants of the folk version were sung, but most began along

the lines of:

John Brown's body lies a-mouldering in the grave,

John Brown's body lies a-mouldering in the grave,

John Brown's body lies a-mouldering in the grave,

But his truth goes marching on.

Glory, glory, hallelujah,

Glory, glory, hallelujah,

Glory, glory, hallelujah,

His truth is marching on.

The abolitionist writer Julia Ward Howe, who had heard soldiers

singing the rousing anthem, composed her more poetically

ambitious

Battle Hymn in late 1861 in an effort to

supply it with better words. Her famous lyrics begin, "Mine eyes

have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord; / He is trampling

out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored; / He hath

loosed the fateful lightning of His terrible swift sword: / His

truth is marching on."

One commonly repeated verse of the original song envisioned the

President of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, swinging from a

crabapple limb: "

They will hang Jeff Davis to a sour apple

tree." A queue of early Joyce annotators—Hodgart and

Worthington, Thornton, Bowen—interpreted this phrase as alluding

to a parody of the

Battle Hymn of the Republic called

We'll

Hang Jeff Davis. Thornton says cryptically that the parody

is "by Turner," and that "Though I know such a song exists, I

have not been able to find a printed copy of it." But it is

hardly necessary to suppose a crude parody of an eloquent

elaboration of a crude original, whose verses, after all, had

been endlessly varied in soldiers' mouths. The Jeff Davis line,

sung three times, appears in many surviving versions of

John

Brown's Body. The detail reproduced here comes from a

piece of sheet music titled

John Brown Song that bears

no date but does feature a colored emblem of Indiana at the top,

presumably because the lines were sung by an Indiana regiment of

federal troops.

§ Many

Irish-Americans fought for the Union in the Civil War, and after

the conclusion of that long and brutal conflict some of them

returned to the old country to join the ill-fated

Fenian revolt of the late 1860s.

John Brown's Body probably began circulating on Irish

lips at this time, repurposed as a song about liberation from a

different kind of tyranny. The song's exaltation of righteous

violence represents one way in which Irish nationalism drew

inspiration from American abolitionism, and the divisive

attitudes that Americans held toward its central figure, the

fanatical John Brown, found close parallels in Irish attitudes

toward the Fenians.

Joyce's deployment of the line about hanging the enemy's

leader from a crabapple tree suggests that this ambivalence

about violent renunciation was still very much in play in the

early 20th century. The threatened murder of Joe Chamberlain,

something that organizers of the December 1899 protest feared,

comes from the mouths of young protesters whose sympathies for

militant revolution ally them with John Brown. Bloom's

instinctive dislike of violence and grudging respect for

institutional order ("Silly billies: mob of young cubs

yelling their guts out . . . Few years' time half of

them magistrates and civil servants") allies him with

the great numbers of American abolitionists who sought

peaceful alternatives to civil butchery.

Two personal communications from Ireland suggest that the

sour apple verse of the song has long played a part in

political rallies there. Cathal Coleman observes that the

great short-story writer Frank O'Connor featured it in "The

Cornet Player Who Betrayed Ireland," and also in his memoir An

Only Child (1961), both times in the context of early

20th century musical duels in the streets of Cork between

political supporters of William O'Brien and his rival John

Redmond. O'Connor's father played the big drum in a band of

O'Brienites, and the story recalls how the son and his

companions "used to parade the street with tin cans and toy

trumpets, singing ‘We’ll hang Johnnie Redmond on a sour

apple tree.’" At a crucial moment in the story, when the

musicians in the adult band have gone off to a pub, two boys

are left to guard the instruments. They take up drums, and

Dickie Ryan starts to sing, "We’ll hang William O’Brien on

a sour apple tree." Dumbstruck, the protagonist realizes

that Dickie means it, and he begins singing, "We’ll hang

Johnnie Redmond on a sour apple tree," until an adult

"hanger-on" of the band barks at him to shut up. Outnumbered

and astonished at the betrayal from within, the boy retreats

to the pub, concealing the news of treachery from his father.

In his memoir, O'Connor recalls that the political policy of

his father's band "was 'Conciliation and Consent', whatever

that meant. The Redmond supporters we called Molly Maguires,

and I have forgotten what their policy was—if they had one.

Our national anthem was God Save Ireland and theirs A

Nation Once Again. I was often filled with pity for the

poor degraded children of the Molly Maguires, who paraded the

streets with their tin cans, singing (to the tune of John

Brown's Body), 'We'll hang William O'Brien on a Sour

Apple Tree' . . . There were frequent riots, and during

election times Father came home with a drumstick up his

sleeve—a useful weapon if he was attacked by the Molly

Maguires." Veteran readers of Ulysses will recall the

pitched battles of Circe: "Wolfe Tone against Henry

Grattan, Smith O'Brien against Daniel O'Connell, Michael

Davitt against Isaac Butt, Justin M'Carthy against Parnell,

Arthur Griffith against John Redmond, John O'Leary against

Lear O'Johnny, Lord Edward Fitzgerald against Lord Gerald

Fitzedward, The O'Donoghue of the Glens against The Glens of

The O'Donoghue."

Vincent Altman O'Connor recalls that John Brown's truth was

still marching on in these battles as recently as the 1960s.

During the 1966 presidential contest, which the aged Éamon de

Valera narrowly won, "marching bands and singing were a

feature of the campaign." Memories of Ireland's own Civil War

were still raw and "a group of Free Staters" in Dublin North

Central sang, "We'll hang De Valera by the balls in

Stephen's Green." O'Connor was 11 impressionable years

old at the time.