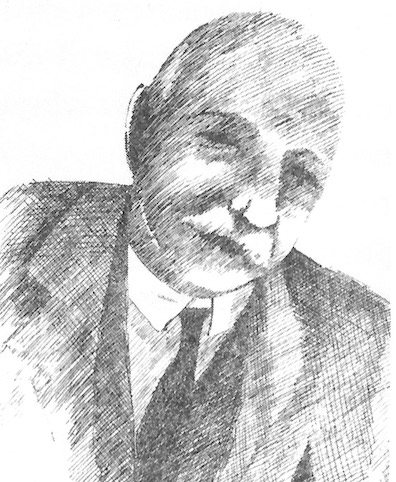

Coming to Dublin in 1873 as a 12-year-old boy from County

Wicklow, Byrne served as an apprentice in one pub before

working his way up to part-ownership in another and then, in

1889, purchasing a run-down tavern at 21 Duke Street which he

reopened under his own name. His life-story thus confirms what

Bloom thinks in Calypso about publicans: "Coming up

redheaded curates from the

county Leitrim, rinsing empties and old man in the cellar.

Then, lo and behold, they blossom out as Adam Findlaters or Dan Tallons."

Vivien Igoe observes that Byrne "was a good listener and had

a way of winning friendships and retaining them. His pub

became the haunt of poets, artists, writers, scholars and

politicians. These included James Joyce, Michael Collins, Arthur Griffith, F. R.

Higgins, Pádraic Ó Conaire, Tom Kettle, Liam O'Flaherty and

William Orpen, who was one of Byrne's greatest friends." A

longer list would include Oliver

St. John Gogarty and James Stephens, and later writers

like Patrick Kavanagh, Brian O'Nolan (Myles na gCopaleen,

Flann O'Brien), Brendan Behan, and Anthony Cronin. Actors

(including the famous gay couple Hilton Edwards and Michael

MacLiammoir), actresses, and dancers also frequented the pub,

attracted by the artistic flair of its interior. Byrne died in

1938.

When Bloom reflects that Byrne's is a "moral" place, several

things jump to his mind: "He doesn't chat. Stands a drink

now and then. But in leapyear once in four. Cashed a cheque

for me once." As the narrative of Lestrygonians continues,

other indications of sound character appear. Byrne doesn't bet

on the horses: "— I wouldn't do anything at all in

that line, Davy Byrne said. It ruined many a man the same

horses." He notices when people are in mourning and

tactfully respects their privacy: "— I never broach

the subject, Davy Byrne said humanely, if I see a gentleman

is in trouble that way. It only brings it up fresh in their

minds." And he recognizes Bloom's uncommon qualities: "Decent

quiet man he is. I often saw him in here and I never once

saw him, you know, over the line. . . . He's a

safe man, I'd say." Like his silent assessment of the

butcher's Jewishness in Calypso, then, Bloom's quiet

appreciation of Byrne's moral qualities seems to reflect an

awareness of shared values. They are birds of a feather.

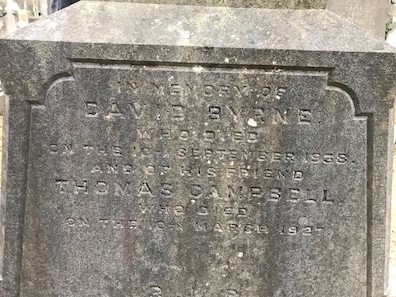

In a personal communication from Dublin, Senan Molony adds

another sympathetic detail to Byrne's biography: in an

intolerant time and place he seems to have been monogamously

devoted to a male partner. Census records of 1901 and 1911

retrieved by Molony show that Byrne was (respectively) "not

married" and "single." Far more remarkably, a tombstone in the

Glasnevin cemetery stands atop two graves and preserves the

memory of two men: "of David Byrne, who died on the 10th

September 1938, and of his friend Thomas Campbell, who died on

the 10th March 1927." Such an inscription, in the repressively

moralistic atmosphere of Ireland in the 1930s, should probably

be seen as a bold defiance of conventional sexual mores.

(Another Thomas Campbell, a

Romantic-era Scottish poet, surfaces twice in Hades—once

anonymously when Bloom recalls a line from one of his poems, and

again by name when he wonders about the authorship of a different poem. These

references are quite definitive, and since the Dublin Campbell

died in 1927 there would be no particular reason to allude to

him in the cemetery chapter. Still, given Joyce's fondness for

name coincidences, it is not inconceivable that he knew of

Byrne's friend and obliquely acknowledged him by bringing in

the poet.)

If indeed Joyce had reason to think that Byrne was

homosexual, that purely natural inclination would not by

itself justify calling the man and his establishment "moral."

But in a time when morality was widely invoked to demean

non-standard sexual orientations, not to mention unacceptably

frank works of literature (Ulysses shows

heteronormative desire to be riven with channels like

voyeurism, adultery, masochism,

and anal eroticism that

render it very non-normative), Joyce's use of the word to

characterize an all-but-out gay man may mask a cutting edge.

What would seem an "immoral" pub to many people becomes a

moral one with the stroke of a pen, suggesting that Joyce's

celebration of human happiness over social conformity extended

into his assessment of same-sex love.

Evidence that Davy Byrne's pub was "moral" in the sense of

tolerating queerness can be found later in the 20th century.

For most of that century Dublin was a very lonely place for

gay men. A 2013 blog by Sam McGrath on the Come Here to

Me! website cites one man's recollections from the

1970s, recorded in Coming Out: Irish Gay Experiences

(2003): "There weren’t many opportunities to meet gay people,

unless you knew of the one bar—two bars, actually, in Dublin

at that time, Bartley Dunne’s and Rice’s … They were the two

pubs and if you hadn’t met gay people, you wouldn’t have known

about these pubs; there was no advertising in those days, and

it was all through word-of-mouth." The same two bars are

mentioned by another gay man, George Fullerton, who is quoted

from Occasions of Sin: Sex and Society in Modern Ireland

(2009) as saying that in the 1960s "I never experienced

discrimination as such, probably because we were largely

invisible."

These two bars near the Gaiety

Theatre and St. Stephen's Green became known as

gay-friendly starting in the late 1950s and early 1960s, along

with King's, another pub in the same area that is mentioned

less often. But there were two more in Duke Street: The Bailey

and Davy Byrne's. The 1971 edition of Fielding's Travel

Guide to Europe noted that "On our latest visit, scads

of hippie-types and Gay Boys were in evidence" in the Bailey,

and it suggested that both that bar and Davy Byrne's, across

the street, were not "recommended for the 'straight'

traveller" (779). It seems likely that the welcoming

atmosphere in Davy Byrne's may have dated back to its original

proprietor. Proof of this is hard to come by, but there are

tantalizing bits of evidence that may be featured in a later

version of this note.

Mentally calculating his day's expenses in Sirens,

Bloom thinks back on the 7d. he spent on a gorgonzola sandwich

and a glass of burgundy in Davy Byrne's. In Circe the

publican himself returns, reliving the bored yawn that he gave

in reply to Nosey Flynn's ramblings about the Freemasons in Lestrygonians:

"— O, it’s a fine order, Nosey Flynn said. They stick to you

when you’re down. I know a fellow was trying to get into it.

But they’re as close as damn it. By God they did right to

keep the women out of it. / Davy Byrne

smiledyawnednodded all in one: / — Iiiiiichaaaaaaach!"

Ithaca mentions the pub yet once more, with a

misremembered address: "David Byrne's licensed premises, 14

Duke Street."