§ As

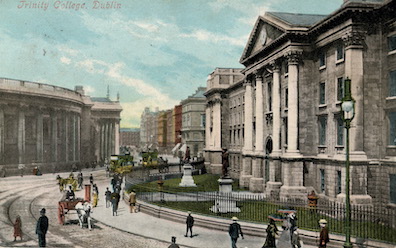

Bloom walks south from Westmoreland Street toward Grafton

Street in Lestrygonians, he passes between the busy

traffic on College Green and the iron

railings of Trinity College, Dublin: "His smile faded as he

walked, a heavy cloud hiding the sun slowly, shadowing

Trinity's surly front. Trams passed one another, ingoing,

outgoing, clanging." The large door of Trinity's main entrance

stands in an imposing four-story Palladian wall adorned with

Corinthian columns. § The

word that the narrative applies to this grand facade once

referred to the manner of an aristocrat ("sir," hence the

original spelling "sirly"). The OED lists a rare

obsolete meaning of "Lordly, majestic" and the more common old

meaning "Masterful, imperious; haughty, arrogrant,

supercilious." In modern democratic times the quality of

supercilious haughtiness associated with feudal lords has

given the word purely negative connotations. Joyce no doubt

intends these more familiar meanings too, since he associates

Trinity with the reactionary politics and social snobbery of

the ruling class.

Trinity College was

founded under letters patent from Queen Elizabeth in 1592 as the

first college of a University of Dublin intended to resemble

Oxford and Cambridge. Although it has remained the university's

sole college, Trinity has a long and distinguished history of

teaching and research, and many of Ireland's greatest writers

and thinkers have earned degrees there. Historically a bastion

of Anglo-Irish Protestants, it functioned throughout the 18th

century as the preserve of the newly empowered Ascendancy class.

In the last few decades of that century the college admitted

Catholics, but until 1793 they could not graduate without

swearing unconscionable oaths of allegiance to the

Anglican

establishment.

During the 19th century Trinity abolished all doctrinal tests,

but strong resentments persisted on both sides of the sectarian

divide. In 1871, responding to the successful 1854 establishment

of a Catholic university (Joyce's alma mater), Catholic bishops

banned their parishioners from attending Trinity (a ban which

some Catholics, like

Oliver St. John Gogarty,

ignored). In the final decades of the century, when Irish

politics were defined by the contest between defenders of Union

and proponents of Home Rule, Trinity faculty and students firmly

espoused the Unionist cause.

In

Lestrygonians Joyce alludes to many key aspects of

this bitter divide, starting with the 1800

Act of Union.

Sixteen paragraphs before he sees the college's "surly front,"

Bloom's path of travel takes him past the Bank of Ireland

building, but the narrative does not refer to it in that way: "

Before

the huge high door of the Irish house of parliament a flock of

pigeons flew." When the Irish Parliament was abolished,

the building that had housed it was sold, with the condition

that it could never again be restored to its original use.

More political resonances follow. As Bloom walks past the bank

he sees uniformed police officers exiting from a station on "

College

street," on the north side of the campus. They make him

think of the massive protests that filled Dublin's streets in

December 1899, on "

the day Joe Chamberlain was given his

degree in Trinity." Awarding an honorary degree to

the

chief government architect of British imperial warmongering in

South Africa was a polemical choice designed to

demonstrate Ireland's acquiescence in the scheme. It backfired,

causing Catholics to take to the streets to show that the

university's political views were not those of all Irish men and

women. Bloom remembers the violent crackdown by policemen and

soldiers, as well as the counter-demonstrators who spilled out

of the campus to confront the protesters: "

And the Trinity

jibs in their mortarboards. Looking for trouble." Then he

thinks more broadly of republican insurrectionists, anticolonial

political movements, plainclothes spies, and police informants.

After these sixteen paragraphs evoking more than a century of

struggle between Anglo-Irish Protestant rulers and Catholics

seeking a voice in the government of their country, Joyce's "

surly

front" resounds with implied meanings. The Trinity facade

is majestic, masterful, lordly, as befits the ruling class that

the college serves. But to middle-class Catholics excluded from

its classrooms and opposed to its Unionist politics it appears

haughty and arrogant, and probably also surly in the modern

sense: churlish, sullen, ill-humored, uncivil. Joyce points up

these implications by having "

a heavy cloud" occlude the

sun as Bloom approaches the college, casting its stonework into

shadow. The narrative notes that "

His smile faded," and

in the four paragraphs that follow this meteorological event his

thoughts become very dark, just as they did when

a cloud

blotted out the sun in

Calypso. The effect of this

entire section of

Lestrygonians is to make Trinity a

darkly forbidding place associated with political repression and

social exclusion.

One of the most eminent Trinity dons of Joyce's era, John

Pentland Mahaffy, the distinguished classicist, brilliant

conversationalist, and devout royalist who mentored both Oscar

Wilde and Gogarty, represented a level of educational

excellence to which poor Catholics could not hope to gain

access. In his biography of Joyce, Richard Ellmann observes

that at this time Trinity "had a more distinguished faculty"

than did University College, and he records Mahaffy's remark

that "James Joyce is a living argument in favor of my

contention that it was a mistake to establish a separate

university for the aborigines of this island––for the

corner-boys who spit into the Liffey" (58). Ellmann does not

provide a date for this remark or speculate about whether

Joyce knew of it, but it is certainly surly, in all senses of

that word.