Brunetto Latini was a 12th century Florentine writer who

today is known almost entirely through the picture that Dante

paints of him in canto 15 of the Inferno. The young

Dante who is traveling through Hell extravagantly admires him.

One of only a handful of people in the entire Comedy

whom he respectfully addresses with the formal "You" (Voi),

and one of only three to address him as a kind of son (figliuol

mio), Brunetto predicts the bitter exile lurking in the

poet's future and urges him to be strong when it comes, just

as Cacciaguida (another father figure) will do in Heaven.

Dante, in turn, wishes that his prayers could save Brunetto

from eternal exile, "For I remember well and now lament / the

cherished, kind, paternal image of You / when, there in the

world, from time to time, / You taught me how man makes

himself immortal (s'etterna)" (82-85).

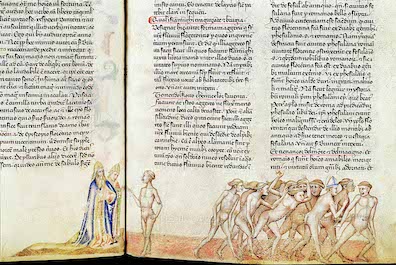

Ironically, Brunetto has failed to eternize himself in any

desirable way in the divine realm: he is eternally condemned

to suffer the rain of fire that tortures a group of men whose

sin is never named but which is almost certainly sodomy. But

his Livres dou Trésor (Books of Treasure), an

encyclopedic prose treatise written in French, says that fame

makes one immortal on earth. And his Tesoretto (Little

Treasure), a narrative poem written in Italian, appears

to have given Dante an inspirational model for how that could

be done. Though unfinished at his death in 1294, it was the

longest such poem to date, and Dante appears to have echoed

several of its passages in his epic poem.

At the end of canto 15 Brunetto implores Dante, "Let my Treasure

(Tesoro), in which I still live on, / be in your mind (Siete...raccomandato)"

(119-20). Many commentators believe that this work is the

well-known French Trésor. But others believe that it

is the unfinished Tesoretto. If the Italian poem did

give Dante inspiration for writing a long narrative poem in

the vernacular, then Brunetto may be pleading for remembrance

of his little-known poem as a kind of encouragement for Dante

to complete his own ambitious narrative, which at this point

is less than one sixth finished. Robert Hollander's commentary

to the Inferno notes that Brunetto's poem refers to

itself three times in the text as the Tesoro, and that

in the first of these he commends (racomando) himself

to the reader. Dante may well be evoking this passage when he

has Brunetto ask that his Tesoro be "raccomandato"

to Dante. And Brunetto seems to be aware that Dante too is

engaged in a massive artistic labor: "Had I not died too soon,

/ seeing that Heaven so favors you, / I would have lent you

comfort in your work (l'opera)" (58-60). Dante seems,

then, to be staging an encounter with another poet who tried

to do something like what he is trying to do, and who offers

him solidarity and encouragement.

Encouraged by his reading of Dante (like Joyce, he studied

Italian at university so he could read him in the original),

Stephen Dedalus appears to have sought out Brunetto's Livres

dou Trésor and read some of it in an Italian

translation. When John Eglinton expresses skepticism about his

view of Hamlet, "Stephen withstood the bane of

miscreant eyes glinting stern under wrinkled brows. A

basilisk. E quando vede l'uomo l'attosca.

Messer Brunetto, I thank thee for the word." The quoted

sentence comes from a description of the mythical basilisk in

the first book of Brunetto's prose compendium: "And when it

sees a man it poisons him." Stephen invokes the Italian

writer, then, as a kind of charm against the malign influence

of Eglinton's disbelief. Rather than encouraging the efforts

of a younger writer on Dublin's literary stage, Eglinton seems

determined to poison him in his cradle. And in fact Eglinton

did more to offend the young Joyce than just glare. In 1904,

as the editor of Dana, he rejected an essay by Joyce

titled A Portrait of the Artist.

Almidano Artifoni plays a quite different role in Wandering

Rocks. A vocal teacher based loosely on an Italian man who

was nine years older than Joyce (Eglinton was based on the

writer William Kirkpatrick Magee, fourteen years older),

Artifoni warmly encourages Stephen to persist in his singing

career because he has a great gift. At the end of the

conversation, which is—significantly—conducted entirely in

Italian, he runs to catch a tram: "Almidano Artifoni,

holding up a baton of rolled music as a signal, trotted on

stout trousers after the Dalkey tram. In vain he trotted,

signalling in vain among the rout of barekneed gillies

smuggling implements of music through Trinity gates." The

scene evokes the end of Inferno 15, where the flakes

of fire oblige Brunetto to break off his talk with Dante and

run after the group of men he left earlier in the canto:

"After he turned back he seemed like one / who races for the

green cloth on the plain / beyond Verona. And he looked more

the winner / than the one who trails the field."

In the races outside Verona the runners ran naked, just as

the homosexuals in Dante's seventh circle do. The winner was

given a piece of green cloth as a trophy, while the loser had

to carry a rooster back to the city, enduring the mockery of

the spectators. Dante's pilgrim says that Brunetto looked like

the winner of the race, but to the reader of his poem he looks

more like a loser, quite literally trailing the field and

spiritually far from "immortal." In the scene on College Green

Stephen's maestro holds up "a baton of rolled

music," signalling not only his status as a contestant

(racers pass batons) but also the honor of artistic mastery

(conductors lead with them). He signals "in vain,"

however, lost in a "rout" of pedestrians and unable to

gain the tram driver's attention. Joyce thus reproduces the

ambiguity in Dante, where Brunetto is a revered and generous

artistic predecessor who has nevertheless lost life's most

important race and who is lost in a shameful crowd.

In Joyce and Dante: The Shaping Imagination (1981),

Mary Reynolds shows that Joyce imitated this scene long before

he began writing Ulysses. Chapter 18 of Stephen

Hero describes a conversation that Stephen conducts with

an old Clongowes schoolmate named Wells who is training to

become a Jesuit priest. Joyce wove many echoes of Inferno

15 into the passage, Reynolds notes, as a way of sharpening

his attack on the Jesuits (44-51). But when he revisited the

Dantean scene in Wandering Rocks, she observes, it was

to help make Artifoni "a fully sympathetic figure, like

Brunetto" (52). Artifoni's "human eyes" contrast sharply with

Eglinton's basilisk gaze. He tells Stephen that he has a

beautiful voice and should not waste his talent. He says that

when he was young he too thought that the world was beastly ("Eppoi

mi sono convinto che il mondo è una bestia"),

echoing Brunetto's advice to Dante to "Let the beasts of

Fiesole (le bestie fiesolane) make

forage / of themselves but spare the plant, / if on their

dung-heap any still springs up" (73-75). And he trots off

after the tram.

Reynolds notes one more echo of Dante in Scylla and

Charybdis that appears to tie in with the allusions to

Brunetto. The chapter describes Stephen "battling against

hopelessness" two sentences before he says that when

Shakespeare wrote Hamlet he had "thirtyfive years of

life, nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita." The

quotation of the opening line of the Inferno recalls

Dante's state of being hopelessly lost at age 35, which

seems relevant to the hope offered him by the older Brunetto.

Although Reynolds does not make the connection, it also

recalls the way Dante was rescued from despair in canto 1 by

another spiritual father: Virgil. Like Brunetto, Virgil is a

writer and father figure who gives Dante hope of surviving his

misfortunes and becoming the poet he knows he can be. Stephen,

who broods on fatherhood throughout Ulysses and who is

discussing it at this moment—"A father, Stephen said,

battling against hopelessness, is a necessary evil"—likewise

finds two older men with sympathetic understanding of his

quest: Artifoni and Bloom.