When Lyster leaves the office just after the chapter opens,

Stephen is left alone with Eglinton and responds harshly to

something he has just said––"Stephen sneered." Eglinton, in

turn, asks him a question "with elder's gall." Magee was

fourteen years older than Joyce, born in Dublin in January

1868. His father was a Presbyterian clergyman sent from

Belfast to Dublin to convert the city's

Catholics. The younger Magee did not adopt his father's

religious faith, but he did retain the political convictions

of most Ulster Protestants. Inveterately opposed to the

nationalist movement, he responded to the founding of the Free

State in 1922 by leaving Ireland for Wales and never

returning.

After attending Erasmus Smith High School, where he knew

William Butler Yeats, and Trinity College, where he was on financial

assistance and won numerous academic prizes (rather like

Joyce at Belvedere), Magee tried to make a name for himself as

a poet. Vivien Igoe says that he gave it up because he was

"thwarted by Yeats's success." Instead he became known as an

essayist. Gifford notes that "Yeats paid him the compliment of

regarding him as 'our one Irish critic'."

For one year in 1904 and 1905 John Eglinton and Fred Ryan

ran a literary journal called Dana. Someone in Scylla

and Charybdis, surely Eglinton, says that "Synge has

promised me an article for Dana too,"

and soon Stephen is seen angling for favor by referring to the

Irish fertility goddess who was the magazine's namesake:

"— As we, or mother Dana, weave and unweave our

bodies, Stephen said, from day to day, their molecules

shuttled to and fro, so does the artist weave and unweave his

image." Later it becomes clear that Stephen has already had

something accepted for publication. Eglinton says, "You are

the only contributor to Dana who asks

for pieces of silver." This detail is autobiographical:

Joyce asked for, and received, a payment of one pound for the

publication of his poem "My love is in a light attire."

Eglinton rejected his next submission, an essay called "A

Portrait of the Artist" that later would morph into the famous

novel.

Perhaps Joyce's mercenary approach had something to do with

the rejection, but all that Eglinton said at the time was, "I

cannot print what I can't understand." The authors of the Blooms

and Barnacles website (www.bloomsandbarnacles.com) note,

however, that "Eglinton admitted later that he regretted

rejecting this early version of Portrait, but at the

time found Joyce’s short story 'pompous and self-conscious',

feeling that it was 'one of those works which becomes

important only when the writer has done or written something

else'." Whatever complex reactions Eglinton may have had to

the essay, he did reject it after publishing another work,

thereby duplicating Joyce's experience with George Russell.

"The Sisters," "Eveline," and "After the Races" ran in the Irish

Homestead, but after hearing protests about

Joyce's immorality Russell turned off the tap. It is fair to

assume that the less than glowing portraits of both men in Ulysses

may have been motivated in part by bitterness.

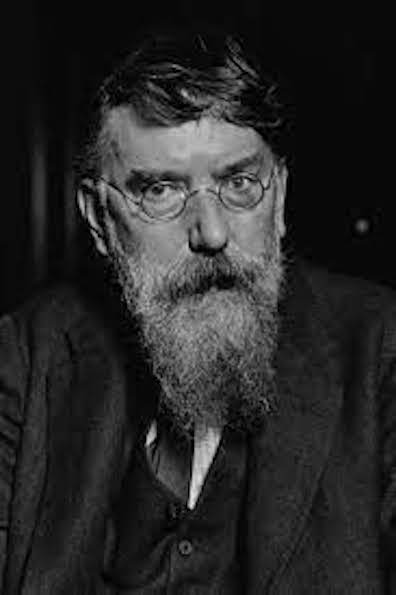

Eglinton fervently admired Russell––his biography, A

memoir of AE, George William Russell, was published in

London in 1937. Stephen thinks of them as a pair: "Mummed in

names: A. E., eon: Magee, John Eglinton. East of the

sun, west of the moon: Tir na n-og. Booted the twain

and staved." Russell founded the Dublin Hermetic Society, and

Eglinton became deeply involved in his branch of Theosophy. Scylla

and Charybdis shows Stephen advancing a this-worldly and

bawdy understanding of Shakespeare against the other-worldly

and chaste proclivities of Eglinton and Russell. At one point

Eglinton calls these abstract, non-biographical approaches "The

highroads." The chapter also glances at one of Joyce's

cruder rejections of Theosophy: "Yogibogeybox in Dawson

chambers. Isis Unveiled. Their Pali

book we tried to pawn." In My Brother's Keeper

Stanlislaus Joyce recounts one element of this adolescent

prank:

Something brought Gogarty and my brother one

afternoon to the room or rooms of the Hermetic Society. I

think they were looking for Russell, for the Hermetic Society

was a place where young would-be mystics met under the

brooding wings of 'their master dear' to read esoteric poetry,

hear discourse of the Father, Son, and 'Holy Breath' and

generally to discuss the dreamy and visionary short-cut to the

solution of the riddle of the Universe....

The room was empty at that hour, but in a

corner the two ribalds found George Roberts' travelling-bag.

George Roberts, afterwards manager for Maunsel and Company,

was a member or frequenter of the Society and had addressed

poems to his 'master dear', but in the flesh he was then a

commercial traveller for women's underwear. Gogarty found a

pair of open drawers in the bag, stretched them out by tying

the strings to two chairs, and by means of another chair fixed

the handle of the Hermetic broom between the legs of the

drawers, while on the hoisted head of it he hung a placard

bearing the legend 'I never did it' and signed 'John

Eglinton'. (254-55)

Russell blamed Joyce for the incident––a bit of history that

no doubt informs the tensions in the library office––and at

the beginning of the chapter Stephen thinks about Theosophical

beliefs like the ones Stanislaus describes. When Eglinton's

insulting joke about Aristotle is rewarded by seeing Russell's

"smiling bearded face," Stephen thinks, "Formless spiritual. Father,

Word and Holy Breath." The lewd mockery of Eglinton's

chastity enters the episode when the similarly chaste Mr. Best

comments on Stephen's remark that there will be no marriage in

heaven, "glorified man, an androgynous angel, being a wife

unto himself." Best laughs, "unmarried, at Eglinton

Johannes, of arts a bachelor." Against this chaste play

on the word "bachelor," Stephen's interior monologue pursues a

more risqué interpretation of man being a wife unto himself.

Wickedly, he thinks, "Unwed, unfancied, ware of wiles, they

fingerponder nightly each his variorum edition of The

Taming of the Shrew."

The picture of Eglinton as a masturbator clearly goes back

to Gogarty's business with the drawers in the Hermetic

Society, and Joyce brings Mulligan into the chapter in part to

continue evoking this incident. As he leaves the library with

Stephen, Mulligan jokes about Eglinton's asexuality: "John

Eglinton, my jo, John, / Why won't you wed a wife?"

And then, "He spluttered to the air: / — O, the

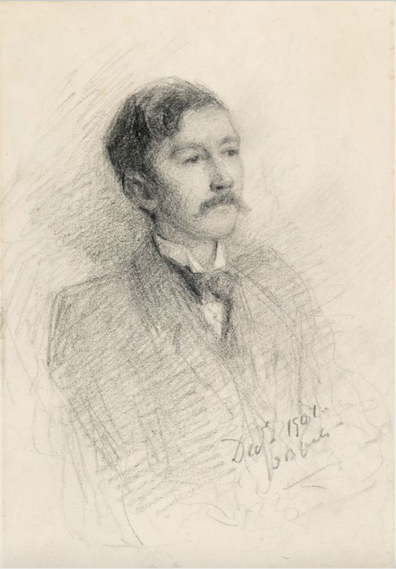

chinless Chinaman! Chin Chon Eg Lin Ton." The photograph here

may be taken to support the view that the man had no chin.

Mulligan continues his pairing of chinlessness and sexlessness

a few sentences later, bursting into a series of couplets on

M'Curdy Atkinson "And that filibustering filibeg / That

never dared to slake his drouth, / Magee that had the

chinless mouth. / Being afraid to marry on earth / They

masturbated for all they were worth."

The chapter encourages only very slightly the notion that

Eglinton and Stephen may have certain interests and

convictions in common. Like Joyce, Eglinton opposed the

softheaded ideals of most writers of the Celtic Revival,

arguing that Irish literature should embrace urban life and

sound universal themes rather than retreating into a

mythologized rural past. When Best mentions that Haines has

gone off to buy a copy of Hyde's Lovesongs of Connaught

he says that "The peatsmoke is going to his head."

Since Eglinton's poems are distinguished by sharp, hard

clarity, this may be a comment on "Celtic" vagueness. But it

is equally possible that he is expressing an Ulster Protestant

contempt for everything associated with rural Irish Catholics.

At several points Stephen respectfully alludes to things that

"Mr Magee" has said ("the new Viennese school," "a saying of

Goethe's," "nature...abhors perfection"). But these are

clearly efforts to draw in the hostile Eglinton and win him

over to the argument about Shakespeare. In response to the

last quotation Eglinton looks up happily, "shybrightly," eyes

"quick with pleasure," while Stephen reflects with mercenary

cunning, "Flatter. Rarely. But flatter."

All known sources yield the impression that Magee was a

loner––iconoclastic, severe, and unjovial. George Moore's

memoir Hail and Farewell calls him “a sort of lonely

thorn tree." He seems to have been strongly shaped by his

father and his Ulster Presbyterian relatives, and also by his

effort to distance himself from them. When Stephen defines

Shakespeare in terms of his family relationships Eglinton

replies that "we have it on high authority that a man's

worst enemies shall be those of his own house and family.

I feel that Russell is right. What do we care for his wife and

father? I should say that only family poets have family

lives." Stephen thinks wryly, "Shy, deny thy kindred, the unco

guid. Shy, supping with the godless, he sneaks the cup. A sire

in Ultonian Antrim bade it him. Visits him here on quarter

days. Mr Magee, sir, there's a gentleman to see you. Me? Says

he's your father, sir. Give me my Wordsworth."

Thanks to Vincent Van Wyk for some very helpful suggestions

made in response to drafts of this note.