One glimpse of John Eglinton's reverence for

George

Russell comes when Scylla and Charybdis uses a

detail from Eglinton's college education to characterize the

relationship: "Glittereyed, his rufous skull close to his

greencapped desklamp sought the face bearded amid darkgreener

shadow, an ollav, holyeyed. He laughed low: a sizar's laugh of

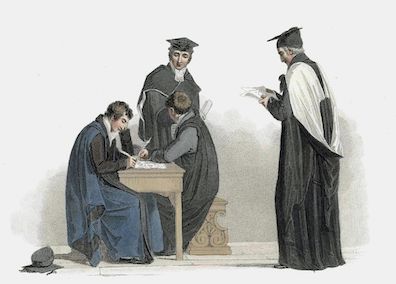

Trinity: unanswered." Sizars were undergraduates at Cambridge

University, in England, and Trinity College, in Dublin, who

received financial assistance from the institution in exchange

for menial work duties. The detail implies a history of

subservience on Eglinton's part.

Students who paid the fees at Cambridge and TCD were called

pensioners. Some promising students whose parents could not

afford the cost were admitted as sizars (occasionally spelled

"sizers") in an arrangement whereby free education, room, and

board were compensated with regular duties that essentially

made them servants to the wealthier students. These

impecunious students, of course, might be just as gifted and

accomplished as their social betters. In many cases they must

have been more so, since they were admitted solely on the

basis of merit rather than family connections, and they knew

that a university education could lift them out of the states

of relative poverty in which they had been raised. Richard

Westfall, a historian of science who wrote a biography of

Isaac Newton––a sizar at Cambridge––shows in Never At Rest

(1980) that from an early time sizars at Cambridge attained

degrees at a much higher rate than did gentlemen (75).

William Kirkpatrick Magee (John Eglinton) was awarded

numerous prizes at TCD. From 1887 to 1893 he won the

Vice-Chancellor's prize for composition in English, Greek, and

Latin four times. He won a similar prize for verse twice, and

a prize for prose twice. But the fact of having been a sizar,

which Joyce keenly noted and memorialized, must have marked

him for life as a social inferior, and the way Joyce mentions

it indicates that it has left permanent scars in his psyche.

His "sizar's laugh of Trinity" in the direction of the

man he reveres suggests an attitude of deference and

ingratiation that he learned at school. It is surely

significant that the laugh goes "unanswered" by

Russell, much as the haughty children of the wealthy at

Trinity would have accepted ingratiating laughs from their

sizars without condescending to echo them. In a personal

communication, Vincent Van Wyk observes that Eglinton's

acerbic manner elsewhere in Scylla has perhaps been

spawned by this disparity in privilege––an adult compensation

for the humiliations of late adolescence.

In a short article "On the History of Sizarship in Trinity

College," Hermathena 13 (1905): 315-18, the famous

Trinity don John

Pentland Mahaffy writes that "Subsizars attended on the

Scholars' table, while the Sizars attended on that of the

Fellows. It was a tradition up to my youth that they dined off

the remains left after the Fellows' dinner, and that they rang

the bell, swept the hall, and performed other menial offices.

This I used to hear from my father, who was a Scholar in 1821;

but I cannot remember whether he described it as existing in

his day, or already obsolete" (315-16). This testimony

suggests that as the 19th century wore on sizars were

subjected to less humiliating treatment than before. But the

indignities before were searing. Here is English historian

William Howitt writing in 1847 about Oliver

Goldsmith:

The family income did not allow him to occupy a

higher rank than that of a sizer, or poor scholar, and this

was mortifying to his sensitive mind. The sizer wears a black

gown of coarse stuff without sleeves, a plain black cloth cap

without a tassel, and dines at the fellows' table after they

have retired. It was at that period far worse; they wore

red caps to distinguish them, and were compelled to

perform derogatory offices; to sweep the courts in the

morning, carry up the dishes from the kitchen to the fellows'

table, and wait in the hall till they had dined. No wonder

that a mind like that of Goldsmith's writhed under the

degradation! He has recorded his own feelings and opinions on

this custom: "Sure pride itself has dictated to the fellows of

our colleges the absurd fashion of being attended at meals,

and on other public occasions, by those poor men who, willing

to be scholars, come in upon some charitable foundation. It

implies a contradiction, for men to be at once learning the

liberal arts and at the same time treated as slaves; at once

studying freedom and practising servitude."

How long did sizars continue to be stigmatized with red caps,

like Jews with yellow stars and homosexuals with pink

triangles in Hitler's Germany? Into Eglinton's time? Gone by

then, but within recent memory? I do not know the answers to

those questions, but the mention of Eglinton's "rufous

skull" suggests an allusion to the practice. Rufous

means reddish brown. According to George Moore's Hail and

Farewell, Eglinton was "a thin small man with dark red

hair growing stiffly over a small skull" (162). In Joyce's

prose his red hair grips his head like a cap, as if his skull

has been permanently marked by his experience of "practising

servitude."

Some servitude is rewarded, however. Eglinton's laughing

efforts to curry Russell's favor make some headway after he

offers up to the oracle a demeaning joke about Aristotle: "He

laughed again at the now smiling bearded face."