Scylla is peppered with strange stylistic

innovations suggesting an impatience with the "initial style":

a narrator acting

like a character, a snippet of Gregorian chant notation,

two imitations of theatrical posters (the second followed by a

list of dramatic characters), a section of dramatic dialogue.

None of these is stranger than what happens after Stephen

pauses in his barrage of arguments and challenges his

listeners to make arguments of their own. Explain, he demands,

Anne Hathaway's poverty in Stratford at a time when her

husband was living richly in London. Explain the "swansong

wherein he has commended her to posterity":

To whom thus Eglinton:

You mean the will.

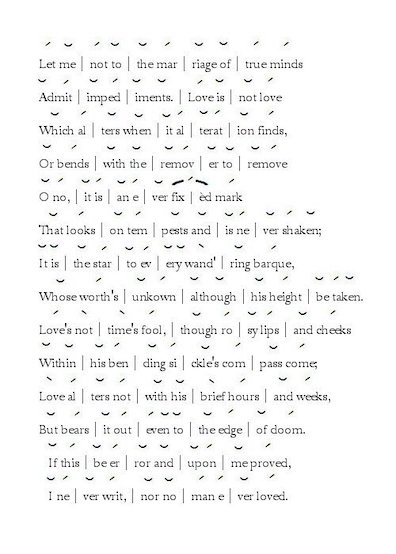

Content-wise, what follows is Eglinton's defensive but

confidently rational argument that bequeathing your "secondbest

bed" to your wife need not imply a sense of sexual betrayal. But

content plays a dull second fiddle here to the formal element: a

radically indented "You mean," introducing what look like twenty

lines of verse. A little farther down the page, the eye sees

what look like the "shared," "split," or "dropped" lines found

in many Shakespeare plays, in which a half line of one

character's dialogue quickly follows a half line of another's,

represented in printed texts by dropping down a line and

continuing to the right.

The way in which "You mean" is positioned on this website

suggests that it may be part of such a dropped line, but not all

editors have positioned it in quite the same way. Some put it

several spaces to the left of the colon, and the Gabler edition

includes no drop at all. My text reproduces the look of the

Shakespeare & Company first printing, which Joyce oversaw.

But even if these ten syllables are not a dropped line—they do

differ from Shakespeare's usage, since only one person is

speaking—they nevertheless arguably make up a single

line

because they scan as highly regular iambic pentameter: "to WHOM

thus EG-lin-ton: you MEAN the WILL."

Shakespeare's verse works constant changes on its underlying

metrical pattern, following the shifting rhythms of human

speech and avoiding metronomic regularity. The presence of a

"pyrrhic" foot of two unaccented syllables in the line above

is neither unusual nor disruptive of the pattern. The

beginning of the next line ("That has been explained") is so

roughly irregular that it is hard to hear any iambic pattern,

but the rhythm is quickly re-established. It is not much

disrupted by the extra unaccented syllables in "jurists" and

"dower" (such so-called "feminine endings" are common in

Shakespeare's lines), by the extra syllable in "knowledge"

(substituting "skill" or "lore" would produce a line of

perfect pentameter), or by the reversal of stress in "She was"

(initial trochees are perhaps the most metrical common

variation in all of Shakespeare). But after these three and a

half lines the rhythm is very strongly disrupted:

Him Satan fleers,

Mocker:

These words form parts of two dropped lines, suggesting that

some other voice has briefly broken into the speech of the first

one. Another fact adds to this impression: roughly stressed

rhythms (/ / u / / u) intrude here, tearing apart the smooth

iambic flow of the first voice.

Regular iambic rhythm returns at "And therefore he left out" and

continues through "The presents for his granddaughter." But then

it begins to die out over the next two and a half lines, as

extra syllables and prose rhythms crowd in. Finally, four short

lines—progressively more truncated, as if the very structure of

verse is being whittled down—bring the pentameter down to

nothing. Three and a half feet, then two, then one, then one

half, and finally nothing at all:

As I believe, to name her

He left her his

Secondbest

Bed.

Punkt

"Punkt" is German for "period" or "full stop"—a

punctuation mark consisting only of a "point" or "dot,"

a single small puncture of the page. Here it suggests

that the diminishing verse lines are approaching a vanishing

point, like the daylight consciousness of Bloom at the

end of Ithaca. Hans Walter Gabler, altering the

practice of earlier texts (including the first edition), puts

a period after this word, but surely this is a mistake. Rather

than a sentence requiring a full stop, it is a full

stop. Like the large dot in Ithaca, it declares a

decisive end to something—the argument advanced in the iambic

lines.

This word does not seem to be spoken, and there is no

indication that it is even thought by any of the men

in the library office. From whose consciousness does it arise?

Perhaps the only good explanation is that it represents an

intervention by the author—or the narrator, or the "Arranger,"

or the text itself, assuming that there is any real difference

among those entities. A similar foreign-language intrusion has

occurred earlier in Scylla when Mulligan enters the

library office: "Entr'acte." This French

term for an intermission between the acts of a drama could

come from Stephen's internal monologue, as he anticipates that

the arrival of the garrulous Mulligan will interrupt his

lecture. But it probably makes more sense as a kind of

authorial stage direction, announcing that the next few pages

will be given over to chatter. "Punkt" seems even more clearly

cut from that cloth.

It is strange to imagine the narrative commenting on itself,

or the author entering into dialogue with his characters, but

the passage under discussion invites such thoughts. Who, after

all, has organized the passage as lines of verse and contrived

to make Eglinton speak in a semblance of blank verse? Who

rudely interrupts his speech? ("Him Satan fleers, / Mocker"

makes no sense whatsoever as something Stephen would say or

think, but it makes good sense as a narrative description

of Stephen: the young man who likes to think of himself as the

Devil is said to be mocking Eglinton's thought process.) Who

diminishes the pentameter lines, making them shrivel away to

nothing? All of these things represent the hidden hand of the

author or narrator, brazenly upending what by the ninth

chapter have become well-established rules of narration. If

this entity can announce its presence with such arbitrary

narrative acts, it may well permit itself to say to Eglinton,

"Punkt," Enough!

The narrative tricks are not quite yet finished. The

stylistic legerdemain that has produced a sonnet's worth of

blank verse concludes with six short lines of pure doggerel

that sound like a mockery of that stately language. A series

of strongly stressed short "e" sounds hammers out a kind of

maniacal parroting of Eglinton's closing words:

Leftherhis

Secondbest

Leftherhis

Bestabed

Secabest

Leftabed.

These repetitive, reeling, increasingly incoherent compounds

cannot be Eglinton's speech. Nor do they sound like Stephen's.

Whatever narrative consciousness pronounced "

Punkt,"

putting an end to Eglinton's speech, now seems to be shaking its

head in disbelief at the inanity of his claim that it was

entirely normal for Shakespeare to bequeath his secondbest bed

to his wife. Having made Eglinton sound a bit like Shakespeare

himself, it first stifles his speech and then declares it to be

stark raving nonsense.