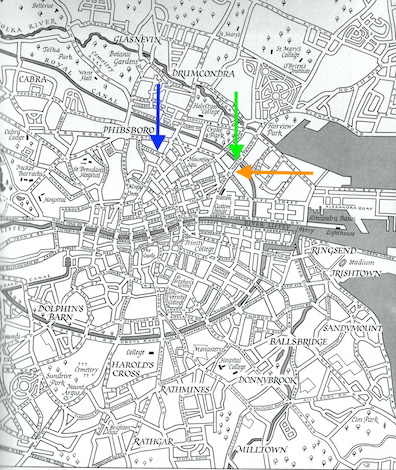

New space-time. Section 2 of Wandering Rocks,

which is quite short, takes place at the entrance to Harry J.

O'Neill's, an "undertaker and job carriage proprietor" at 164

North Strand Road according to Thom's directory. This

business was on the northeastern edge of the city, close to

the spot where the road crosses the Royal Canal, and Father

Conmee has passed it on his walk to Artane in section 1.

One narrative interpolation glances at an action of Conmee's

that took place in that section (though it could well be

viewed as happening in this one), and another at an event that

is represented in section 3. These links to the sections just

before and after show two kinds of impression that Joyce's

interpolations can create: of perfect and less than perfect

simultaneity.

In section 1 Father Conmee passed "H. J. O'Neill's funeral

establishment where Corny Kelleher totted figures in the

daybook while he chewed a blade of hay. A constable on his

beat saluted Father Conmee and Father Conmee saluted the

constable." In section 2 Corny Kelleher is again seen "chewing

his blade of hay" and talking to the constable, but this

cannot be the same moment because the priest has now moved

slightly farther along the road out of the city: "Father

John Conmee stepped into the Dollymount tram on Newcomen

bridge," where the North Strand Road crosses the canal

and leaves the central city. The sentence echoes a very

similar one in section 1––"On Newcomen bridge the very

reverend John Conmee...stepped on to an outward bound

tram"––but there it came four sentences after the ones

about seeing Corny and saluting the constable. Additional

evidence of time passing is provided by the fact that Corny

Kelleher now closes "his long daybook," whereas in section 1

he "totted figures in the daybook" as Conmee passed by.

The temporal and spatial disjunctions reinforce the sense of

an interpolation––a jump to a different scene. But Clive Hart

argues that what feels like an interpolation from section 1

actually is not: "Although Conmee is some distance away, Corny

Kelleher would nevertheless have had no difficulty in seeing

him board the tram, had he taken the trouble to look. This

passage, which belongs on the fringes of the same narrative

and topographical context, is not therefore strictly speaking

an interpolation" (James Joyce's Dublin, 48). Joyce

performs the same trick in section 15, when a sentence

describing three men meeting on the steps of City Hall sounds

like it is intruding on the action of Martin Cunningham and

his friends descending Cork Hill––until one stops to realize

that Cork Hill goes directly past the steps of City Hall, so

the two scenes are in fact identical.

In section 2 the proximity is not quite so immediate as that,

but Hart's observation is accurate. O'Neill's was one of

several buildings on the North Strand Road destroyed when a

German bomber dropped four high explosive bombs on the area on

the night of 31 May 1941, and there has been a lot of

reconstruction since then, so the precise location may be a

little uncertain, but it would have been on the south side of

the road just 300-400 feet away from the Newcomen Bridge. In a

personal communication, Matt Rudge, who lives nearby, observes

that "Number 164 would have existed on the site of the

existing James Larkin House.... From that vantage point, it

would have been quite possible for Corny Kelleher to see Fr.

Conmee board the tram. They are on a similar elevation."

One can still make a case for the sentence being an

interpolation, however. In addition to its close linguistic

echoing of a sentence in section 1 (a feature of every

interpolation in Wandering Rocks), and the way it jogs

time forward a little (another feature of many

interpolations), there is the discontinuity between the two

actions. Even if Kelleher could have spotted Conmee boarding

the tram "had he taken the trouble to look," it seems

narratively significant that he does not look. He is

shown "looking idly out" of the shop, evidently concerned not

to be seen looking very intently at anything in the presence

of this constable who is pumping a covert informant ("It's

very close") for news of a "particular party." Since Kelleher

is not straining to catch sight of Conmee, it does not seem

quite right to say that the two stories share "the same

narrative and topographical context." The effect of the

sentence about Conmee boarding a tram is to make readers

suddenly recall an action from the first section, and that is

the essence of Joyce's interpolations.

The other intruding sentence is quite unambiguously an

interpolation: "Corny Kelleher sped a silent jet of

hayjuice arching from his mouth while a generous white arm

from a window in Eccles street flung forth a coin." Here

the prose asserts exact simultaneity ("while") with an action

happening in a very different place, nearly a mile to the

northwest. The next section shows this action happening at the

Blooms' house: "A plump bare generous arm shone, was seen,

held forth from a white petticoatbodice and taut shiftstraps.

A woman's hand flung forth a coin over the area railings." The

two passages are linked by the "arching" descent of the spit

and the coin. Hart observes also that "Kelleher is concerned

with death, Molly with life" (Critical Essays, 203).

The simultaneity feels plausible because section 2 is so

brief and section 3 comes immediately after. When the Eccles

Street scene reappears via interpolation in section 9,

however, the narrative distance is reflected in a temporal gap

comparable to the one created by Conmee's progress up the

North Strand Road. When Molly opens her window to fling a coin

to the beggar, a card advertising Unfurnished Apartments

falls from the sash. In section 9 the card reappears

in the window. By such mechanisms the interpolations in

Wandering Rocks can create impressions not only of

simultaneity but also of forward motion, advancing action

along the arrow of time as traditional novels do.