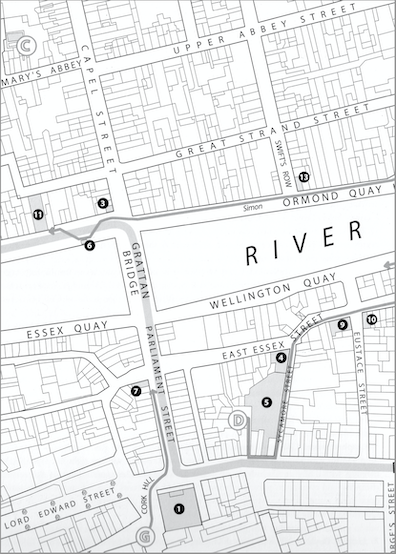

Newcomers can easily become disoriented in the labyrinthine

medieval streets of Dublin. The "tiny square of Crampton

court" is one of its more obscure nooks. Two narrow

alleyways between buildings on Dame Street in the south and

Essex Street East in the north meet in a small courtyard at

the back entrance of the Olympia Theatre, which in Joyce's

youth was Dan Lowrey's Music Hall and, after 1897, the Empire

Palace Theatre. Section 9 opens with Tom Rochford showing his

three companions a device for letting music hall patrons know

which number is currently being performed, and then Lenehan

and M'Coy go "out" into this tiny courtyard, so they must be

exiting from the back door of the music hall.

The subsequent street directions show that the two men do not

walk down to Essex Street but instead go up to Dame Street,

where they turn left and then left again on Sycamore Street.

Joyce makes the journey more confusing by mentioning the music

hall twice under its two names (one of them misspelled, as

Slote notes): "They passed Dan Lowry's musichall where

Marie Kendall, charming soubrette, smiled on them from a

poster a dauby smile. / Going down the path of

Sycamore street beside the Empire musichall Lenehan

showed M'Coy how the whole thing was." It sounds as if they

are passing different buildings but in fact they are seeing

the same establishment, which had entrances on both its Dame

Street and Sycamore Street facades as indicated in Thom's

1904 directory.

When they get to Essex Street, they find themselves "At

the Dolphin," a hotel and restaurant which once stood on

the corner. Here, instead of turning left toward the Ormond

Hotel, Lenehan takes a right toward "Lynam's," a bookmaker he knows.

(No one today can say with certainty which building may have

housed this illegal betting operation, and Joyce does not give

readers much help.) Responding to Lenehan's asking what time

it is, "M'Coy peered into Marcus Tertius Moses' sombre

office, then at O'Neill's clock." They have now moved

one block east to the meeting of Essex and Eustace Street,

where rival tea merchants sat on opposite corners of the

intersection. The time, M'Coy says, is "After three," which

means that in England it is after 3:25.

The race there was scheduled to start at 3, so it has already

happened, but the news was not due to reach Dublin by

telegraph until 4 so bookies were still taking bets. (Parallax

and technology here add temporal wrinkles to the deepening

spatial ones.)

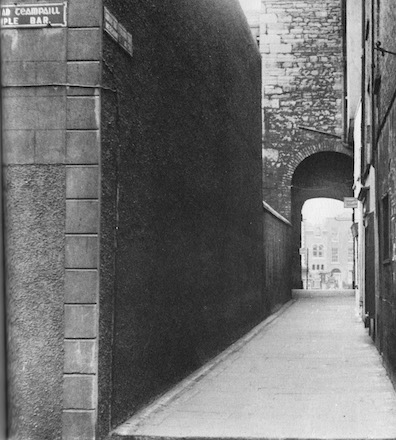

Lenehan leads M'Coy forward into "Temple bar," which

continues Essex Street East eastward under a new name––an

omnipresent source of confusion to people visiting Dublin. (At

its other end Temple Bar becomes Fleet Street. There are

dozens, perhaps hundreds of similar examples in this old

city.) He leaves M'Coy standing there while he goes to talk to

the bookmaker, returning shortly later to report that it's

"Even money." Then he directs his companion "Through here.

/ They went up the steps and under Merchants' arch. A

darkbacked figure scanned books on the hawker's cart."

Merchants' Arch is another quirky, captivating feature of the

old Dublin streets. It provides a mid-block pedestrian

shortcut from Temple Bar to Wellington Quay via another narrow

alleyway and a tall narrow archway.

The following section will show (almost certainly) that the

"darkbacked figure" standing at the cart is Leopold Bloom,

since he is seen there browsing in a nearby bookstore. Thus it

may possibly seem that the sentence mentioning this man is an

interpolation drawing attention to section 10, but Lenehan and

M'Coy do actually see Bloom, as evidenced by the long

discussion they have about him after passing by. The

uncertainty a reader may feel here repeats the trick played in

section 2, when a sentence about Father Conmee boarding a tram

seems to be an interpolation echoing the previous section (it

may in fact

be one) but is also happening in present time and space.

Finally the narrative shows Lenehan and M'Coy coming out of

the alley and moving west: "They crossed to the metal

bridge and went along Wellington quay by the riverwall."

There is potential for a final bit of confusion here. The span

called the Metal Bridge or Ha'Penny Bridge does cross the

Liffey beyond the Merchants' Arch alleyway, so being told that

the two men "crossed to the metal bridge" may create the

impression that they take this bridge across the river. But in

fact they only cross the road. Spurning the bridge, they turn

left and walk along the riverine side of Wellington Quay. This

will take them to the Grattan Bridge, which they could have

accessed much more quickly from Crampton Court were it not for

Lenehan's detour to visit the bookmaker.

Readers who follow all these spatial twists and turns must

also recognize that they are not entering locations

evoked by four interpolated passages. The first looks ahead to

section 19: "Lawyers of the past, haughty, pleading, beheld

pass from the consolidated taxing office to Nisi Prius court

Richie Goulding carrying the costbag of Goulding, Collis and

Ward and heard rustling from the admiralty division of

king's bench to the court of appeal an elderly female with

false teeth smiling incredulously and a black silk skirt of

great amplitude." This scene is set farther west along

the quays in the entrance hall of the Four

Courts building, which lies beyond the Ormond on the

north bank of the river. So far in this episode, every

interpolation has borne some evident thematic connection to

the section it interrupts, usually to sentences just before or

after. This one is hard to make sense of in that way, and that

is not its only puzzling feature. It also stands in a strange

temporal relation to the next interpolation.

This one too anticipates section 19, glancing even farther

west to Phoenix Park where the viceregal procession is setting

out: "The gates of the drive opened wide to give egress to

the viceregal cavalcade." The horses of the procession

clearly echo the horses that Lenehan is betting on, but

hearing about the cavalcade after hearing about the "Lawyers

of the past" is odd, because readers have become accustomed to

interpolations that either evoke simultaneity or move time

slightly forward. Here, the order of the two interpolations

appears to reverse the actual order of events. Section 19

shows Richie Goulding standing "In the porch of Four Courts"

and watching the cavalcade go by, several sentences after

the cavalcade is shown leaving through the gates of Phoenix

Park––as well it should, since the parade moves east along the

river, from the park to "Kingsbridge," to "Bloody bridge," to

"Queen's and Whitworth bridges," to the Four Courts.

In section 9 one hears first of Richie Goulding in the Four

Courts and then, oddly, of the procession leaving Phoenix

Park. But this time there is an evident solution to the

puzzle, though it does involve a narrative trick requiring

readers to pay close attention. If one looks closely at the

interpolation, it does not say that Richie Goulding saw the

viceroy, as in section 19. It says instead that the lawyers in

the entrance hall saw Richie Goulding. This means that

the interpolation is representing an earlier moment in the

action, unrepresented in section 19, when Richie had not yet

made his way out of the building. After he emerges onto the

porch that fronts the quay he sees the viceroy passing below

its steps. So, by a sly trick, the forward movement of time is

both threatened and preserved. Joyce uses this interpolation

to jump to a moment earlier than the actions seen in the final

section.

In his fourth interpolation he does the opposite, moving time

forward to a later unrepresented moment. This one revisits the

facade of the Blooms' house as glimpsed in section 3:

"A card Unfurnished Apartments reappeared on the

windowsash of number 7 Eccles street." In section 3 the

card advertising rooms for rent falls out of Molly's window.

In section 9 it reappears in the window. The implication is

that some time passes between the two sections. It is probably

impossible to say how much time, but a sense of mimetic

verisimilitude is engendered by imagining Molly noticing that

the card has fallen out, going downstairs and walking outside

to pick it up, taking care of other domestic tasks, and

eventually replacing it in the window. (It is hard for me to

imagine Hart's justification for saying that the card falls

out at 3:16 and is replaced at 3:17. Surely more time has

passed between section 3 and section 9?) This interpolation,

unlike the one about the statues of lawyers in the Four

Courts, also weaves a thematic continuity with other details

in the section, as Lenehan is engaged in telling a lascivious

story about Molly Bloom.

The third interpolation anticipates section 18, where Paddy

Dignam's son Patsy will be seen leaving a butcher shop on

William Street, quite a few blocks to the southeast: "Master

Patrick Aloysius Dignam came out of Mangan's, late

Fehrenbach's, carrying a pound and a half of porksteaks."

Clive Hart observes that there is an "ironic similarity"

between the Glencree Reformatory where Lenehan's story begins

and the O'Brien Institute where Father Conmee is trying to

find a place for young Dignam (Critical Essays,

208). This seems correct, but he also notes "The contrast in

the quality of the foodstuffs." A contrast there certainly is

(at the annual fundraising dinner there were "port wine and

sherry and curacao," and "Cold joints galore and mince pies"),

but I wonder if the funeral dinner at the Dignam house isn't

in its own small way unusually extravagant.

Making sense of the spatial movements in section 9 is arduous

work. The most crowded previous section, Father

Conmee's walk to Artane, covered a lot of ground and

glanced at many streets and now-defunct institutions, but it

started and ended at prominent landmarks and followed a more

or less linear course. Section 9, by contrast, starts in an

unnamed interior space, moves into a small open-air nook

unfamiliar even to many Dubliners, uses two names for one

building, and follows a circuitous walking course that punches

through city blocks but is by no means the shortest distance

between two points. Two of its four interpolations jump to

familiar places but tinker with the time, requiring readers to

augment the narration with things that happen earlier or

later, and what might seem to be a fifth interpolation taking

readers to the following section in fact is happening in

present time and space. Added to all these intricacies are the

multiple thematic threads––sexual arousal, fine eating, harsh

educational institutions, horseracing––that can be teased out

of the interstices between interpolations and surrounding

text.

It is almost as if, in this centrally placed section (number

9 of 19), Joyce wanted to maximize the disorienting jumps

across space, time, people, and subject matters that he was

exploring throughout the entire chapter. The reader who can

get through the labyrinth holding on to all these threads

deserves a medal. Things get easier in the next chunk of text.

Much as Calypso provides comforting clarity to readers

who have struggled through the obscurities of Proteus,

section 10 provides some relief from the challenges of section

9. It stays in one spot, somewhere near the bookseller's cart.