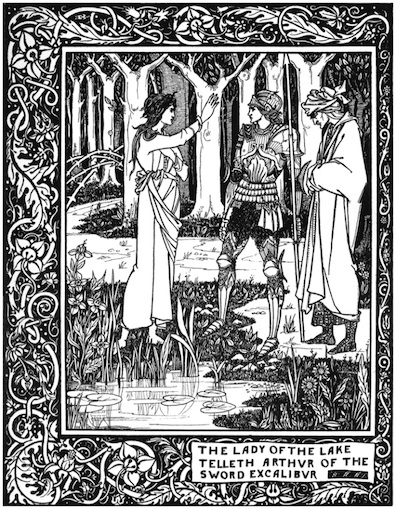

At the end of the Morte d'Arthur (Death of Arthur),

posthumously published by English printer William Caxton in

1485, the author identifies himself as "Syr Thomas Maleore

knyght." He says that he completed the work in the ninth year

of the reign of Edward IV (that reign began on 4 March 1461)

and he prays to be released from prison. In blunt, un-ornate

English prose he re-tells stories from the many Arthurian

romances that had circulated for centuries, mostly in verse

and mostly in French. Many of these romances had focused on

courtly love, but Malory's interest lies in the male

camaraderie that unites the knights of the Round Table until

the adultery of Launcelot and Guenever unleashes conflicts

that destroy it.

The choice of Malory allows Joyce to continue presenting the

men in the common-room as knights, but the tone now changes

from mirthful wonder to somber deliberation, and the focus

narrows from the roomful of young men to just three

characters: Bloom, Lenehan, and a nurse (unnamed, but she is

probably Miss Callan). Presented as if she is an emissary from

a convent ("this good sister"), she steps into the room

to ask that the young men keep their voices down, "for there

was above one quick with child, a gentle dame, whose time hied

fast." Bloom hastens to honor her request and looks for help

to "a franklin that hight Lenehan," because he "was older than

any of the tother." No help at all, Lenehan responds

flippantly and downs another drink. The narrative praises

Bloom as a man who is good, meek, kind, true, and dedicated to

the service of ladies, albeit (repeating a slur heard in Cyclops)

one that has been known to lay "husbandly hand under hen." At

the end of the paragraph, stressing Bloom's compassion for

Mrs. Purefoy's suffering, there is a brief return to Anglo-Saxon

alliteration, as predicted in Joyce's letter to Frank

Budgen: "Woman's woe with wonder pondering."

"Meanwhile" is a favorite locution of Malory's: he says "the

meanwhile" 36 times, and "this meanwhile" another six. Sam

Slote and his collaborators document many such words and

phrases in this not very long paragraph: "This meanwhile"

("This meanwhile came a messenger"), "our alther liege Lord"

("our alther liege lord," "alther" meaning "of all"), "leave

their wassailing" ("Leave thys mornynge and wepyng,"

carousing replacing grieving), "whose time hied fast"

("my tyme hyeth fast," Mrs. Purefoy's birth replacing Arthur's

death), "Sir Leopold heard on the upfloor cry on high"

("Sir Galahad heard in the leaves cry on high"), "I marvel,

said he, that it be not come or now" ("I merveylle, sayd

Arthur, that the knight would not speke"), "a franklin that

hight Lenehan" ("a knight that hight Naram," "hight"

meaning "was called"), "But, said he, or it be long too she

will bring forth" ("but, or it be long too, he shall do

me homage"), "that stood tofore him" ("a knight that

stood afore him" and "tofore the incarnation of our Lord"), "quaffed

as far as he might" ("he threw the sword as far into the

water as he might"), "to their both's health" ("to our

both's destruction"), "a passing good man" ("a passing

good man of his body"), "the goodliest guest...the

meekest man and the kindest that ever...the very

truest knight of the world one that ever did minion service

to lady gentle" ("and thou were the truest lover of a

synful man that ever loved woman; and thou were the kyndest

man that ever strake with swerde; and thou were the godelyest

persone that ever cam emonge prees of knyghtes; and thou was

the mekest man and the gentyllest that ever ete in halle

emonge ladies"; "very truest knight of the world one"

("the worthiest knight of the world one"). There are three

more echoes of Malory's prose, Slote observes, in the third

paragraph: "gramercy" ("Gramercy, said Sir Launcelot"),

"so jeopard her person" ("they marveilled that he would

jeoparde his persone so alone"); "That is truth" ("That

is truth, said king Arthur").

Impressive as this list is, it does not encompass all the

individual words that Joyce took from Malory: "reverence"

of someone is a term used in the Morte d'Arthur

("making to him reverence"), as is "ware" (there are

countless examples, all meaning "aware"). Saying "by cause"

instead of "because" ("him thought it should be his brother

Balin by cause of his two swords, but by cause he knew not his

shield he deemed it was not he") is another Maloryism in the

first paragraph. And in the fourth paragraph, when the chapter

briefly returns to Bloom after moving to different styles and

subject matters, there is a final intense burst of Malory-like

vocabulary: "But sir Leopold was passing grave maugre his

word by cause he still had pity of the terrorcausing

shrieking of shrill women in their labour." The word "shrieking" is

used once in the Morte d'Arthur, "by cause"

four times, "maugre" nine times, and "passing"

(an adverb meaning "very" or "extremely") an extraordinary 141

times. No doubt other echoes of Malory remain to be found.

Rather than simply skimming passages in Peacock's anthology or

Saintsbury's critical study, Joyce must have immersed himself

in the Morte d'Arthur.

Why apply this style to this material? One answer may be that

the first paragraph represents the disharmonious interaction

of two men. In Sources and Structures, Robert Janusko

observes that "the struggle of two male antagonists" is a

recurrent theme in the Morte d'Arthur: King Arthur is

"set up in opposition to the evil King Rience, who is,

ironically, the King of Ireland, and Balin against Balan,

brothers who kill each other by mistake as a result of

enchantment" (62). There are many other examples (Arthur and

Launcelot, Mark and Tristram, Tristram and Launcelot, Bors and

Lionel, Pinel and Gawaine, Launcelot and Meliagrance,

Agravaine and Launcelot, Gawaine and Launcelot), culminating

in the disastrous opposition of Arthur and Mordred. In

addition to these conflicts, another analogue can be found in

the moral example that Arthur sets for his knights. In Joyce's

scene, where rowdy young men gathered around a table perform a

poor imitation of the Round Table, Bloom tries to act as a

calming example of mature masculinity. When he fails to enlist

Lenehan in his cause his noble intentions come to naught, as

Arthur's do at the end of Malory's work.

Both Gifford and Slote see this paragraph as stylistically

continuous with the following ones: Gifford says that all four

suggest the style of Malory, while Slote says that they

combine "Malory, Berners, More, Elyot, Wyclif." But most of

the demonstrable borrowings from Malory occur in the first

paragraph, and nearly all of those from 16th century writers

occur in the second, third, and fourth, so it seems possible

that Joyce intended multiple sections rather than a single

long one. One piece of evidence argues otherwise: in a March

1920 letter to Frank Budgen about the composition of Oxen,

Joyce wrote that after Mandeville he was imitating "Malory's Morte

d'Arthur ('but that franklin Lenehan was prompt ever to

pour them so that at the least way mirth should not lack')."

The sentence that he quotes comes from the third

paragraph, suggesting that Malory continues to be the dominant

model. But this indication of authorial design need not be

regarded as definitive. As Janusko notes, Joyce wrote the

letter while he was still working on Oxen, so it is

possible that he "altered his intention by the time his

writing was complete or that he never intended the letter to

be a complete and detailed listing" (62).

Janusko comments on the distinct break between the first

paragraph and the following ones: "Between the end of the

Mandeville parody ('Thanked be Almighty God') and the

beginning of the 'Elizabethan chronicle' parody there are at

least twenty-five phrases that Joyce copied from Malory. But

there are also borrowings in these pages from, among others,

Wyclif, Fisher, Holinshed, North, Elyot, More, and especially

John Bourchier, Lord Berners. It is, in fact, Lord Berners who

seems to be a primary source from 'Now let us speak of that

fellowship' [the beginning of the second paragraph], a typical

Berners introduction, to the end of the section designated by

Joyce as a Malory parody, including the passage in which

appear the lines cited by Joyce in his letter as a sample of

Malory.... The Malory phrases are concentrated in the passage

beginning 'This meanwhile this good sister' and ending

'Woman's woe with wonder pondering' [the first paragraph]"

(61-62).

To some degree the question of how to divide Oxen

into sections is academic, since Joyce regularly sprinkled

quotations into sections of text before or after those where

they best fit. But such critical division is necessary, given

the succession of strikingly different prose styles that he

clearly intended for this chapter and the way he applies them

to a succession of shifting subject matters. In this instance

the first paragraph is rendered distinct from the second and

third not only because echoes of Malory dominate the one and

are nearly absent in the others, but also because the prose

works in the two later paragraphs are drawn from multiple

authors writing in the next century, and because the subject

matters in these paragraphs are radically different.

The paragraph beginning "Now meanwhile this good sister"

describes Bloom's futile effort to quiet the disturbing

uproar. The one beginning "Now let us speak of that

fellowship that was there" turns to the other members of

the party, identifying each in turn. The one beginning "For

they were right witty scholars" presents their

conversation, ballooning with wild comical talk. These later

paragraphs feel very distant, both tonally and materially,

from the sober pondering of decent behavior in the first. But

then the fourth paragraph, beginning "But sir Leopold was

passing grave," returns to Bloom's compassionate

thoughts. The return of Malory-like vocabulary in this last

paragraph signals a kind of ABBA structure across the four

paragraphs.