Though "Mandeville"

claimed to be an English knight, there is no historical record

of such a man. The

Travels were probably not composed in

English: the earliest surviving text is in French, and some

scholars have inferred that an Anglo-Norman original preceded

it. The Middle English version, however, became one of the

foundations of English prose, with other late 14th century works

by Geoffrey Chaucer and John Wycliffe. Joyce could have

encountered it both in

George

Saintsbury's masterful study of English Prose Rhythm

and in William Peacock's

English Prose from Mandeville to

Ruskin (London, 1903), an anthology chosen "to illustrate

the development of English prose" (v). Both Saintsbury and

Peacock emphasize the historical importance of the stories'

prose, written when the English language was beginning to assume

its modern shape.

The style is highly engaging but not highly sophisticated.

Saintsbury observes that "On the whole, one may say that Sir

John's style is that of the better but simpler class of verse

romance—

dismetred, freed from rhyme, and from the

expletives which were the curse of rhymed verse romance itself;

but arranged for the most part in very short sentences,

introduced (exactly like those of a child telling stories) by

'And.' I open a page of Halliwell's edition absolutely at

random: the sentences are not quite so short as they are

sometimes, but there are eleven of them in thirty-three lines of

large and widely-spaced print; ten of which begin with 'and,'

and the eleventh with 'also.' Every now and then, especially

when he comes to the choice things—the 'Lady of the Land,' the

'Watching of the Sparhawk,' the 'Origin of Roses,' the 'Valley

of the Devil's Head'—he sometimes expands his sentences and

makes them slightly more periodic, but they are still rather

cumulative than anything more" (64).

Joyce reproduces this naive effect exactly, while tossing in a

few echoes of Chaucerian English and the King James Bible. Of

the nineteen sentences before his concluding "Thanked be

Almighty God," seventeen begin with "And," one with "Also," and

one with "But." The longer sentences are produced either by

tacking on additional compounding conjunctions ("and there

nighed them," "and he said," "and it was upheld," "but they

durst not move") or by using conjunctions to initiate simple

explanatory clauses ("sithen it had happed," "for he was sore

wounded," "for he was a man of cautels," "though she trowed

well," "for he never drank"). This breathless string of

conjunctions is well suited to the air of rapturous wonder in

which Joyce describes the hospital's common-room: there was a

table held up by enchanted dwarves, and it had shining swords

and knives on it, and also magical drinking vessels and fishes

without heads, and people in the castle made spirits produce

bubbles and they made serpents wind themselves around poles!

Saintsbury quotes from one of the four "choice things" he found

in the

Travels, and Peacock reproduces that story along

with two others. It tells of a woman who has taken the shape of

a huge dragon, "And they of the Isles call her Lady of the Land.

And she lieth in an old castle, in a cave, and sheweth

twice or thrice in the year. And she doth no harm to no man, but

if men do her harm. And she was thus

changed and

transformed, from a fair damsel, into likeness of a dragon,

by a goddess that was cleped Diana. And men say, that she shall

so endure in that form of a dragon, unto the time that a knight

come, that is so hardy, that dare come to her and kiss her on

the mouth; and then shall she turn again to her own kind, and be

a woman again." The story tells how several different knights

failed to surmount this challenge and died.

Janusko discounts the

influence of this story, since "Joyce does not seem to have

copied anything from" it onto his notesheets (60). But it might

well have inspired him to imagine the common-room as an ominous

"

castle" which Bloom tries to avoid entering, and also to

recast his bee-sting as a spear-wound received from "

a

horrible and dreadful dragon." Janusko identifies another

likely model in the story "Of a Rich Man, that Made a Marvellous

Castle, and Cleped it Paradise; and of His Subtlety." The rich

man invites knights into his castle, and Mandeville says that

"often-time, he was revenged of his enemies

by his subtle

deceits and false cautels." In the

Oxen passage "

subtility"

is attributed to Bloom ("

a man of cautels and a subtile"),

who later in

Ulysses will invite Stephen into his house

with the crafty intention of involving him with his wife or

daughter. Janusko observes that Joyce recorded phrases from yet

another of Saintsbury's "choice things," the story "Of the

Devil's head in the Valley Perilous," which "concerns the

penetration of a marvelous and dangerous place, one of the

entries of hell" (61), suggesting that it too could have

prompted his fancy of a perilous entrance.

Any or all of these three stories could have inspired Joyce's

first paragraph, which tells of a "

traveller" who resists

the invitation to enter a "

marvellous castle." Joyce

added some lovely flourishes—he calls Dixon a "

learningknight"

(Joseph Dixon was a medical student who received his M.D. in

December 1904), and he describes Bloom, who has come fresh from

his encounter with Gerty Macdowell, as "

sore of limb after

many marches environing in divers lands and sometime venery"—but

he stays within the outlines of Mandeville's conception.

In the second paragraph, though, Joyce gave his imagination

freer rein. In the Mandevillean spirit of childlike wonder he

asks his readers to suppose that the figures carved into the

legs of the wooden table "

durst not move for enchantment";

that the forks and knives on the table were forged "

by

swinking demons out of white flames that they fix in the horns

of buffalos and stags"; that the glasses have been blown

out of "

seasand and the air by a warlock with his breath that

he blares into them like to bubbles"; that sardines are "

strange

fishes withouten heads" held in a "

vat of silver that

was moved by craft to open"; that bread dough "

by aid

of certain angry spirits that they do into it swells up

wondrously like to a vast mountain"; and that hops plants

are serpents trained to "

entwine themselves up on long sticks

out of the ground" and give up their "

scales" so

that men may "brew out a beverage like to mead."

Details in the

Travels certainly inspired some of these

transformations. The tin can "moved by craft" quotes verbatim

from chapter 30 of the medieval text, and the "fishes withouten

heads" recall Asian creatures in chapter 24: "

monsters and

folk disfigured, some without heads, some with great ears,

some with one eye, some giants, some with horses’ feet, and many

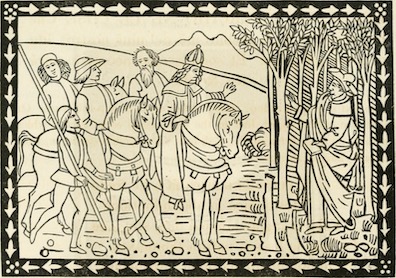

other diverse shape against kind." The headless folk appeared in

countless illustrations of the

Travels in the 1400s and

1500s and inspired Shakespeare's "Anthropophagi, and men whose

heads / Do grow beneath their shoulders" (

Othello

1.3.144-45). The enchanted dwarves holding up the table likewise

may owe something to a passage in chapter 23 that describes the

throne of the great Chan of Cathay: "

And at four corners of

the mountour be four serpents of gold." (This

French-derived word is obscure, but

The Century Dictionary

gives "throne" as one definition of "mounture," citing this very

passage.)

Details like these suggest that Joyce read widely in the

Travels,

far beyond the brief excerpts in Saintsbury and Peacock, but

they do not detract from the brilliance of his invention.

Mandeville writes matter-of-factly of wonders in far-off lands.

Joyce ingeniously suggests that a magical reality may underlie

the mundane facts of Dublin life. He outdoes Mandeville at his

own game.

Joyce's third paragraph provides an indication of why Bloom

regards the "castle" as dangerous (he does not like to drink

immoderately, and likes drunken society even less), and of how

he is "subtle" (he pours his drink into his neighbor's glass

without being detected). The paragraph ends with another clear

echo of the Mandevillean text: "

Thanked be Almighty God."

This phrase appears verbatim in chapters 21 and 31 of the

Travels,

and near equivalents can be found in the Prologue and chapter

15.

Joyce's extensive reading of Mandeville appears also in the

Middle English vocabulary sprinkled throughout these three

paragraphs, especially the first one. Some of these words are

staples of the Travels:

"mickle" (great, much)

"meat" (food of any kind)

"yclept" ["cleped" or "clept" in Mandeville] (called,

named)

"sithen" (since)

"cautels" (craftiness, trickery)

"trowed" (believed)

"contrarious" (opposed)

"list" (will, inclination)

"marches" (walks, but also remote boundary territories)

"environing" (surrounding, extending around)

"durst" (dared)

"full fair" (very beautiful)

"ne" (nor)

"wight" (man)

"natheless" (nevertheless)

"apertly" (openly, clearly)

"no manner" (no kind)

"voided" (emptied)

Joyce threw in other medieval words he knew. Calling Bloom "childe

Leopold" makes him a man of noble birth who has not yet

attained knighthood. Saying that he "did up his beaver"

imagines him raising the lower part of his helmet (the Middle

English "bever") to drink beer—or perhaps, as Sam Slote

suggests, simply raising his drink (also "bever") to his lips.

When the narrative says that nurse Callan "was of his avis,"

it means that she shared Bloom's "advice" (i.e., counsel,

opinion), and her chastisement of Dixon likewise uses an

archaic version of a familiar word: "repreved" means

simply "reproved." Similarly, "halp" means "helped,"

and "mandement" means "command." That "the traveller

Leopold was couth" to Dixon means that he was

known to him. The "swinking demons" are laboring. The

neighbor who "nist not of his wile" did not know that

Bloom had poured drink into his glass.

Bloom's desire to "go otherwhither" needs no gloss, but

this archaic and rare word, cited just once by the OED in

a 16th century text, is a philologist's delight. The Lord

knows where Joyce found it, but he does seem to be echoing a

sentence from Mandeville's Prologue which says that a tribe

without a chieftain is like "a flock of sheep without a

shepherd; the which departeth and disperseth and wit never whither

to go."