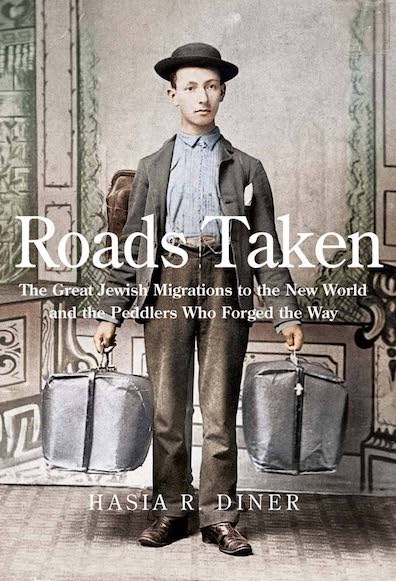

In Roads Taken: The Great Jewish Migrations to the New

World and the Peddlers Who Forged the Way (2015), Hasia

Diner seeks the human realities beneath the stereotypical

picture of bearded, dark-clothed Jewish men peddling wares in

the streets. Many of these men were young––it was physically

demanding work to carry loads weighing more than 100 pounds

for long distances, and dangerous to carry cash. They came to

the doors of people's houses and established relationships

with them, making friendly talk and thereby dispelling

ignorant suspicions about Jews. They sold clothes and other

small marketable goods, accepted orders, made deliveries.

Although many of their customers had very little disposable

income, the salesmen fed their appetites for small luxuries in

the way that Sears catalogues and the Amazon site would later.

Sometimes relations were so cordial that they were invited to

stay the night before heading off again in the morning. They

saved money from their hard labors and often used it to found

less itinerant businesses later in their lives.

This sociological phenomenon studied in Diner's book received

a powerful impetus in the last decades of the 19th century

when Jews fleeing pogroms in Russia and eastern Europe

streamed westward in search of better lives. Their diaspora

took them to frontiers in the Americas, South Africa, and

Australia, and also in Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. Bloom's

father emigrated from Hungary, passed through London, and took

up the profession of traveling salesman in Dublin. Oxen

recounts how his son followed in his footsteps just after

finishing school:

That young figure of then is seen, precociously

manly, walking on a nipping morning from the old house in

Clanbrassil street to the high school, his booksatchel on him

bandolierwise, and in it a goodly hunk of wheaten loaf, a

mother's thought. Or it is the same figure, a year or so gone

over, in his first hard hat (ah, that was a day!),

already on the road, a fullfledged traveller for the

family firm, equipped with an orderbook, a scented

handkerchief (not for show only), his case of bright

trinketware (alas! a thing now of the past!) and a quiverful

of compliant smiles for this or that halfwon housewife

reckoning it out upon her fingertips or for a budding

virgin, shyly acknowledging (but the heart? tell me!) his

studied baisemoins. The scent, the smile, but, more than

these, the dark eyes and oleaginous address, brought home at

duskfall many a commission to the head of the firm, seated

with Jacob's pipe after like labours in the paternal ingle.

The saccharine tone of these sentences suggests some possible

underlying irony about Bloom's energetic salesmanship, and for

a moment the narrative dips into outright mockery with the

word "oleaginous." But what is most striking about the

passage is its confirmation of the doorstep intimacies that

Diner describes. Far from seeming a wandering Jew, or a dangerous

anti-Christ, or a scheming Shylock, to Dublin's poor Catholic

housewives and their daughters Bloom was a charmer, even a bit

of a heartthrob.

After his marriage, when he and Molly were enduring financial

hardships, they turned their flat on Holles Street into a

used-clothing shop specializing in the concert wear familiar

from Molly's singing career. In Sirens Simon Dedalus

recalls how he "saved the situation" for Ben Dollard one night

by finding him a suit to wear in a concert. "Our friend Bloom

turned in handy that night," Dedalus says. "I knew he was on

the rocks.... The wife was playing the piano in the coffee

palace on Saturdays for a very trifling consideration and who

was it gave me the wheeze she was doing the other business?

Do you remember? We had to search all Holles street to find

them till the chap in Keogh's gave us the number. Remember?...

By God, she had some luxurious operacloaks and things

there.... Merrion square style. Balldresses, by God, and court

dresses. He wouldn't take any money either. What? Any God's

quantity of cocked hats and boleros and trunkhose. What?"

True to the upwardly mobile ethos of Jewish entrepreneurs,

Bloom moved on to better jobs, better dwellings, a comfortable

bank account, and an investment in Canadian railway stock. His

father saved enough money to buy a hotel in County Clare.

Through many centuries, in many lands, this pattern of

financial success has earned Jews enmity from the Christians

around them. Various Catholics in Joyce's Dublin scorn Bloom's

economic prudence, speculate about his riches, and deplore his

lack of Christian charity, but Joyce pointedly refutes the

stereotypes. In the anecdote about the used-clothing business,

he makes his protagonist un-grasping even at a time when he

was desperately poor: "He wouldn't take any money either."

For Bloom, the traveling salesman's trick of getting ahead by

befriending the people with whom you hope to do business has

lasted a lifetime.