"Sawbones" is commonly recognized slang for a surgeon

or physician, and of all the medical students only one, Dixon,

is seen acting like a doctor in the maternity hospital. The

actual Joseph Francis Dixon did not receive his medical degree

from Trinity College until December 1904, and early in the

chapter he is called a "learningknight," but clearly he has

attained some rank that confers responsibilities. The chapter

refers to his treating patients at the Mater Misericordiae

hospital, and when Nurse Callan comes into the common room

with a question she speaks "a few words in a low tone to young

Mr Dixon." When the students spill out onto the street "Dixon

follows," so it may be that he hangs back long enough to

excuse his absence and communicate some instructions.

Apparently he is far enough behind the pack for the others to

wonder what has happened to him, but close enough that he soon

appears: "Hurrah there, Dix!"

Various annotators, starting with Gifford, have identified "Where

the Henry Nevil" as rhyming slang for "Where the devil?"

Rhyming slang is the Cockney way of cryptically replacing a

word with a rhyming phrase––"trouble and strife" for wife,

"apples and pears" for stairs, "bottle and stopper" for

copper, "cuts and scratches" for matches, "early hours" for

flowers, "satin and silk" for milk. The many dozens or even

hundreds of such expressions imply semantic linkage between

the two terms: a wife causes strife, apples and pears are

arranged in tiers on carts, cops put a stop to things, matches

often don't light when struck, flower sellers show up early at

Covent Garden, milk is smooth. Gifford notes two men named

Henry Neville who might be referenced in Joyce's expression,

one a Catholic professor at Maynooth and the other an English

actor known for his roles in Dion Boucicault's plays. He does

not specify how either may resemble the devil.

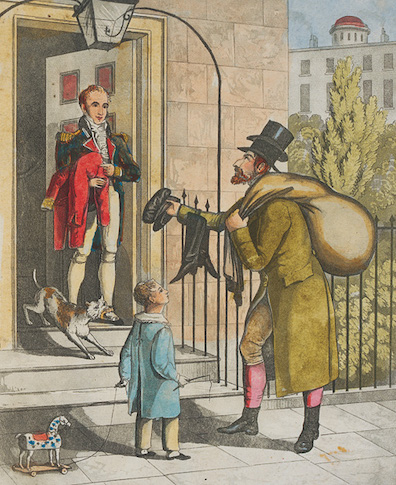

The second person inquired after, "ole clo," is

somehow associated with old clothes. Gifford surmises that

this would be Bloom, since Sirens reveals that he and

Molly ran a secondhand clothing business when they lived in

Holles Street, and "the phrase also alludes to the tradition

that dealing in old clothes was a Jewish (and somewhat

deceptive or dishonest) trade." These inferences make a lot of

sense. Bloom got his start in adult life as a door-to-door

salesman, like his father, and it seems likely that this

later gave him the idea of starting a used-clothing business.

Most traveling salesmen in the 19th century were Jewish, and

they often received enmity from people who distrusted their

ethnicity, their rootlessness, and the competition they posed

to established merchants. Among the many goods that they

peddled, clothes were perhaps the most famous. In London

Labour and the London Poor (1851), Henry

Mayhew observes that "street-Jews, engaged in the

purchase of second-hand clothes" had been seen on the streets

of London since the 18th century. "Now, as during the last

century," he writes, these people fill "every street, square,

and road, with the monotonous cry, sometimes like a bleat, of

'Clo’! Clo’!'”

These cries evidently became a common way of demeaning Jews.

In a personal communication, Jamie Salomon notes that Maurice

Samuel's The Great Hatred, a study of antisemitism

published in 1940, identifies "old clo' man" as an anti-Jewish

slur (17). Samuel describes someone using the phrase in a way

that suggests it was a widely recognized idiom in the first

half of the 20th century (107). Salomon supposes that the

person referring to Bloom as an old clo' man could be either

Mulligan or Lenehan. Mulligan uses two other common

antisemitic slurs, "sheeny" and "Ikey Moses," to refer to Bloom

in Scylla and Charybdis, and in Wandering Rocks

Lenehan tells M'Coy that Bloom is "not one of your common or

garden... You know...," while in Cyclops he jumps to

the antisemitic assumption that he is greedy with money: "The

courthouse is a blind. He had a few bob on Throwaway

and he's gone to gather in the shekels."

Either of these men might have reason to inquire after

Bloom's location. Lenehan is a working man rather than a

student and could feel some kinship with the Jew on that

score. Mulligan calls Stephen's attention to Bloom in the

library, insinuating that Bloom has sexual designs on him, and

he is startled to find him sitting in the hospital's common

room: "seeing the stranger, he made him a civil bow and said,

Pray, sir, was you in need of any professional assistance we

could give?" The word "stranger" itself may convey

anti-Jewish sentiment, and later in the chapter this word is

associated with both men: "The gods too are ever kind, Lenehan

said. If I had poor luck with Bass's mare perhaps this draught

of his may serve me more propensely. He was laying his hand

upon a winejar: Malachi saw it and withheld his act, pointing

to the stranger and to the scarlet label."

In an alternative interpretation, Slote and his collaborators

suggest that the old clo' man is Stephen, since he is wearing

old clothes

and shoes

that Mulligan gave him. This reading too could be justified

contextually: whoever is speaking might well want to know

whether the man who proposed the drinking trip is still with

them, and a heartbeat later Stephen is seen emerging from the

hospital into the street ("Jay, look at the drunken minister

coming out of the maternity hospal!"). But after the first

chapter no one in Ulysses mentions that Mulligan has

loaned clothes to Stephen, and no one comments on those

clothes looking old. Pasting an antisemitic label on Bloom

seems more plausible both narratively and linguistically.

In context, "Forward the ribbon counter" seems like it

should mean "Let's move on to Burke's," and it does. According

to Partridge (cited by Slote and his colleagues), "ribbon" is

"alcoholic spirits," so a bar serves ribbons over the counter

much as a sewing shop does. (As Gifford notes, in Hades

Simon Dedalus calls Mulligan a "counterjumper's son,"

referring to clothing shops.)

"Sorra one of me knows" seems like it should mean

something like "Sorry, I don't know," and the reality is close

to that. Jorn Barger calls it a Scottish way of saying "Not

one of me knows," inferring that the speaker must be the

Scotsman Crotthers. The expression is equally Irish, however.

Dolan's Dictionary of Hiberno-English calls "sorra,

also sorrow" a word "used to express absence or emphatic

negative." Dolan quotes from Jeremiah Hogan's The English

Language in Ireland (1927): "sorrow as a mild

imprecation and emphatic negative is mediaeval English, and

survives in Scotland and Ireland." One of the examples that he

cites is identical to Joyce's usage: "'the sorra one of me

knows', I don't know." On a notesheet for Oxen

Joyce wrote down the equivalent "Not a one of me knows," and

in Finnegans Wake he uses this expression with a

different verb: "But sarra one of me cares a brambling ram"

(624.14). The etymological connection between negation and

sorrow can be appreciated in an example that Paul Clements

offers in a 24 September 2019 article in the Irish Times.

He observes that "a wife returning from shopping who complains

'Sorra thing could I find' means there was nothing suitable in

the shops––'sorra' was from sorrow, expressing

disappointment."