Alexander Graham Bell and his assistant Thomas Sumner Tainter

invented the device in 1880. Bell regarded it as his "greatest

achievement," more important even than the telephone, and had

to be dissuaded from naming his second daughter Photophone.

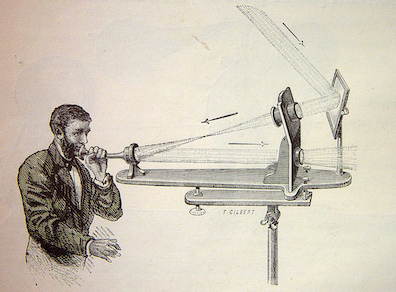

His invention worked much like a telephone but transmitted

sounds over a beam of light rather than a copper wire. At the

end of a speaking tube, a mirror made of thin flexible

material responded to the variations in air pressure produced

by the sound waves of the speaker's voice, becoming

alternately concave and convex. These motions created

corresponding pulses in the brightness of a beam of light

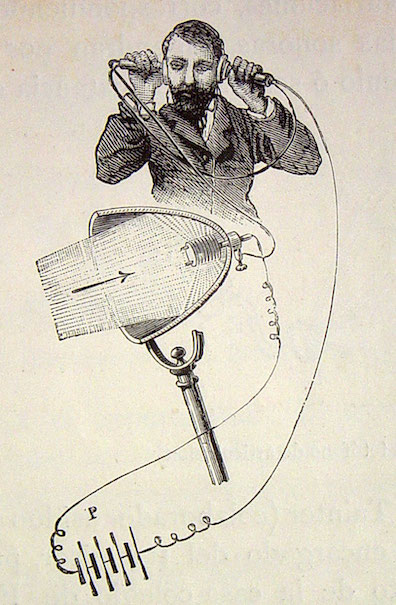

reflected off the other side of the mirror. On the receiving

end, a parabolic mirror focused the beam of light onto a

photoreceptor, where its pulses were converted back into sound

waves. The invention soon was made electronic, with

electromagnetic earphones like those used in the telephone,

but in its first iteration no electricity was involved: the

device was fully photoacoustic.

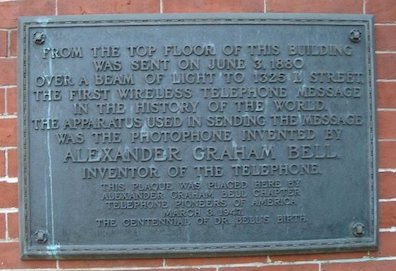

Bell and Tainter successfully tested their photophone in

three experiments in 1880. In the last and most ambitious of

these, they achieved wireless communication between two

rooftops about 700 feet (213 meters) apart in Washington,

D.C., sending signals between them on a beam of reflected

sunlight. The solar source of light for the device (Edison's

development of commercially viable incandescent bulbs was

happening at exactly the same time, so sunlight was the only

powerful source available) did not, it seems, lead anyone to

call it a "sunphone," but similar names were proposed.

The French scientist Ernest Mercadier, another inventor of

incandescent light bulbs, persuaded Bell for a while to use

the term "radiophone" because the device's mirrors relied on

the sun's radiant energy.

By 1904 telephones had gradually started to appear in cities

(Ulysses mentions them in five chapters), and Marconi's

radios were proving capable of transmitting signals over

considerable distances, but the photophone was not a feature

of everyday life. From 1901 to 1904 a German scientist named

Ernst Ruhmer conducted a series of experiments that extended

the device's range to several miles, using naval searchlights

in some models to show that the technology could work even at

night. The British navy, and other European armed forces,

continued to develop and adopt photophones for several decades

afterwards, so Joyce might well have heard reports of the

device's potential when he began writing Circe in

1920.

It is possible that none of this technology lies behind

Joyce's reference to a sunphone, because Thomas Jefferson

Shelton popularized that word in the 1910s and 20s as an

aspect of his cosmic vibrations. As Harald Beck and John

Simpson note on a JJON page, the Miami Herald

reported on 27 September 1916 that "T. J. Shelton

advertises Sunphone and Sunsense, which ‘leads you into real

and genuine telepathy so that you can talk to God, your

neighbor, and yourself’. ‘Sunphone and Sunsense’, he

says, is dictated by himself the way he thinks it ought to be

written and taken down by his wife the way she thinks it ought

to be written, thus giving the product of both brains and

leaving the last word where it belongs both in new and old

thought." On 15 October 1921 the Oakland Tribune

advertised "Sunphone Sermons By T. J. Shelton, Preacher

Writer Teacher" in the Hotel Oakland.

Given Joyce's prodigious propensity for layering multiple

signifying contexts on top of one another, however, it makes

sense to consider that he may be alluding both to Shelton and

to the technological device. Indeed, it seems quite likely

that reports of the revolutionary technology inspired Shelton

to dream up a new catchy, lucrative label for marketing his

telepathic gifts. Nothing in Beck and Simpson's reporting

indicates that he treated the sunphone idea as anything other

than a vague metaphor for instantaneous spiritual

communication. In Joyce's hands, though, the telepathy

involves telephony: Elijah operates a "trunk line" and

offers his subscribers "the cutest snappiest line out."

Following him, one can "Book through to eternity junction."

The associative logic strongly recalls Stephen's thoughts in Proteus,

where umbilical cords become telephone lines connecting mystic

monks to the realm of divinity: "The cords of all link back,

strandentwining cable of all flesh. That is why mystic monks.

Will you be as gods? Gaze in your omphalos. Hello! Kinch here.

Put me on to Edenville. Aleph, alpha: nought, nought, one."

If Elijah's words do mockingly combine a huckster's

metaphysics with groundbreaking scientific technology, it

would not be the first time that Joyce made such a seemingly

bizarre connection. Far from seconding Baudelaire's

suspicion that science and metaphysics are antithetical

principles, Joyce repeatedly suggests that the burgeoning

discoveries and inventions of the Victorian era promise to

enlarge perception, understanding, and even emotional and

spiritual experience. Elijah's words about vibrations and

sunphones are bracketed by sounds of a gramophone

singing "Jerusalem! Open your gates and sing Hosanna" and at

the end of his spiel he joins in. In Hades Bloom

thinks of the potential for gramophones and photographs to

keep memories of the departed alive, and of putting telephones

in coffins in case they wake up. The stereoscope

becomes a fulcrum on which Stephen can toggle back and forth

between ordinary perception and spiritual revelation. Parallax,

based on the same optical principles, suggests the benefits of

viewing one's experiences from multiple angles.