Walking past the

Aston Quay "timeball" that

fell each day at 1 PM to let ships on the Liffey reset their

chronometers, Bloom thinks that it runs on time established by

the Dunsink Observatory on the northwest edge of Dublin, which

in turn reminds him of a Dublin-born astronomer who had long

been the director before taking a post at Cambridge in 1892: "

After

one. Timeball on the ballastoffice is down. Dunsink time.

Fascinating little book that is of sir Robert Ball's.

Parallax. I never exactly understood. There's a

priest. Could ask him. Par. It's Greek. Parallel, parallax."

Dictionaries of ancient Greek define

parallax as the

adverbial form of

parallassein = to change. Like

"parallel" it is built from the prefix

para = beside,

near, beyond, apart from, contrary to.

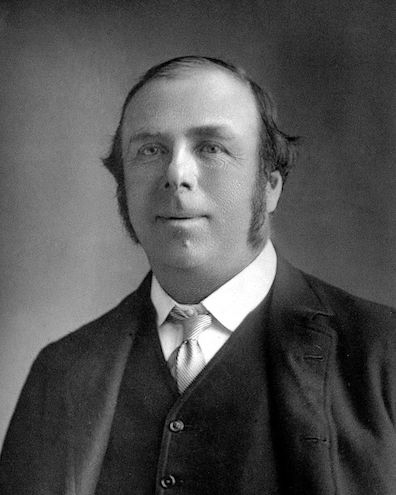

Sir Robert Ball (1840-1913) delivered some 2,500 lectures on

popular science and wrote about astronomy in straightforward

prose.

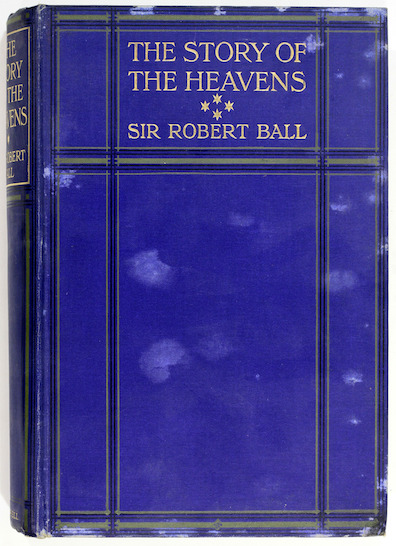

Ithaca reveals that his "little book,"

The

Story of the Heavens (1886), sits on Bloom's bookshelf in

"blue cloth" covers. The book often employs the concept of

parallax in somewhat challenging ways, but it illustrates the

basic idea with an experiment that any sighted person can

perform:

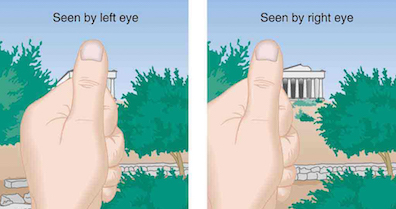

We must first explain clearly the conception which

is known to astronomers by the name of parallax; for it

is by parallax that the distance of the sun, or, indeed, the

distance of any other celestial body, must be determined. Let

us take a simple illustration. Stand near a window whence you

can look at buildings, or the trees, the clouds, or any

distant objects. Place on the glass a thin strip of paper

vertically in the middle of one of the panes. Close the right

eye, and note with the left eye the position of the strip of

paper relatively to the objects in the background. Then, while

still remaining in the same position, close the left eye and

again observe the position of the strip of paper with the

right eye. You will find that the position of the paper on the

background has changed. (181-82)

A recursive loop later in Lestrygonians indicates

that Bloom may have grasped the idea here: different lines of

sight will afford slightly different contextual views of an

object. Standing in front of Yeates & Son, a shop that

sold precision optics, he recalls that the timeball on the

quayside corner of the Ballast Office was linked not to

Dunsink but to the Greenwich Observatory southeast of London.

Dunsink time was displayed on the clockface on the building's

Westmoreland Street façade: "Now that I come to think of

it, that ball falls at Greenwich time. It's the clock is

worked by an electric wire from Dunsink. Must go out there

some first Saturday of the month. If I could get an

introduction to professor Joly or learn up something about

his family. That would do to: man always feels

complimented. Flattery where least expected. Nobleman proud to

be descended from some king's mistress. His foremother. Lay it

on with a trowel. Cap in hand goes through the land. Not

go in and blurt out what you know you're not to: what's

parallax? Show this gentleman the door. / Ah. / His hand

fell again to his side. / Never know anything about it. Waste

of time." More in a moment on Bloom's raised hand, which

strongly suggests that he once tried Sir Robert's experiment.

In 1904 the Dunsink observatory was indeed open to the public

on the first Saturday of every month, and another eminent

Irish astronomer, Charles Joly, was the director. Bloom

supposes that if he showed up for one of these open houses,

flattery might induce Joly to disclose a mystery that learned

scientists keep hidden from ordinary people. In addition to

the divide between amateurs and professionals, social class

plays a part in Bloom's feeling of being excluded from those

in the know. In Circe he pretentiously inserts himself

into the Anglo-Irish ruling elite: "I was just chatting

this afternoon at the viceregal lodge to my old pals, sir

Robert and lady Ball, astronomer royal at the levee. Sir

Bob, I said..." Ball was married to a woman named

Frances Elizabeth Steele.

But Bloom's scheming is comically, poignantly unnecessary. In

a blog published by the Atlantic on 2 February 2012,

"Joyce and the Internet: What Leopold Bloom Didn't Know," Alan

Jacobs observes that specialized scientific knowledge was

indeed much harder to come by in Bloom's time than it is now,

when popular science writing abounds and everything under the

sun can be found on the internet, but Bloom already has all he

needs: a copy of Ball's book, and a prime example of parallax

in the two discordant times.

Greenwich time was approximately 25 minutes ahead of Dunsink

time. When the highly accurate timeball fell at 1 PM,

the highly accurate clock on the same building showed 12:35.

Why? Because astronomers at the two observatories, sighting

the sun at the same moment, saw it standing in two slightly

different places in the sky. The novel's way of introducing

these time differences suggests that Joyce did not include the

disparity as a mere scientific curiosity, but rather to

indicate that Bloom understands parallax better than he thinks

he does. Why have parallax occur to him just after reflecting

on the timeball's link to Dunsink, and then again just after

remembering that it is linked to Greenwich, if not to imply

some latent awareness of its relevance to the different times?

This inference from Joyce's textual juxtapositions is

strengthened by the remarkable fact that Lestrygonians

offers a second instance of Bloom almost glimpsing

parallax, now in a more directly visual way. And here we

return to the raised hand. In a personal communication,Vincent

Van Wyk has suggested to me that the little experiment that

Bloom performs while standing in front of Yeates & Son may

be relevant to parallax: "He faced about and, standing

between the awnings, held out his right hand at arm's length

towards the sun. Wanted to try that often. Yes: completely.

The tip of his little finger blotted out the sun's disk.

Must be the focus where the rays cross. If I had black

glasses." All of Bloom's thoughts about Professor Joly

take place during this interval while he stands pointing a

finger at the sun.

The hypothesis he is testing is fairly trivial. His finger is

vastly less wide than the sun, but it is also vastly closer,

so sun and finger appear to be the same size, and the one is

"blotted out" by the other. This is plausible enough. The

writer of a 2009 blog called "Bloom's little finger" on The

peacocks' tail, a website devoted to mathematics and

culture, points out that the moon can eclipse the sun because

the distances involved are coincidentally perfect for making

their diameters appear equal. In the same way, a soccer ball

will cover the sun at a distance of 25 meters from the

observer, and an orange will do the trick at a distance of 10

meters.

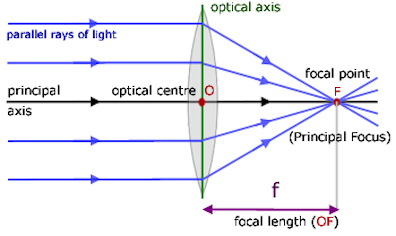

But two odd details in Bloom's experiment suggest a different

scientific interest. One is the conceptual apparatus that he

proposes. He thinks that his finger makes a "focus" (i.e., a

focal point) where "rays cross," coming from far edges of the

sun and slicing past his eyes on the opposite sides, as light

rays focused by a lens will do. This may be true, but such a

model is not needed to explain his finger's eclipse of the

sun, and, as will be seen in a moment, it has considerable

relevance to the phenomenon of parallax. A second problematic

detail, which the writer of the blog fails to observe, is that

a finger held at arm's length from the eyes will not eclipse

the sun quite so perfectly as the moon does. The sun

disappears if one eye is kept closed, but not if both are

open. (Try this at home, carefully!) Bloom must be looking

with one eye closed, then. His wish for "black glasses"

indicates awareness of the pain he would suffer if he opened

the other.

And this means that he is almost but not quite performing the

experiment he read about in Sir Robert Ball's book. The book

proposes fixing a thin strip of paper to a window pane, but

raising a finger is just as effective. The illustration here

shows how a raised thumb will appear to move across the

background when one eye is closed and the other opened. The

line of sight from the left eye to the finger affords one view

of the background, while the line from the right eye gives a

slightly different view. Bloom is perfectly positioned to

confirm this finding (at the risk of burning his retina), but

he does not perform the crucial step of switching eyes.

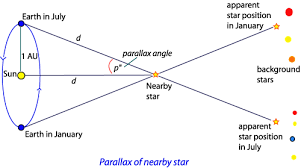

The idea of rays crossing at a focus also evokes parallax.

Scientists had noted as early as the 16th century that nearby

stars might be seen moving across a field of more distant

stars, because every six months the earth's revolution around

the sun takes it to a new vantage point similar to that of a

second eye. Viewing a nearby star in January and again in July

should make it appear to move across the background, because

it forms a kind of focal point for rays coming from two

different parts of the sky. Just as animal brains process the

angle described by slightly different images to gauge distance, astronomers

should be able to measure the angle at this focus and

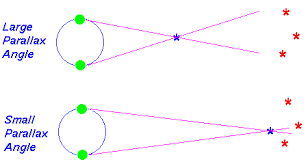

mathematically calculate the star's distance. The greater the

distance to the star (d in the first astronomical

sketch), the less it would "move" (as shown in the bottom

figure of the second sketch), yielding a smaller measurable

angle (p). With more movement and a larger angle (as in

the top figure), the distance would be less. Since all stars

but one are so very far away in comparison to the earth's

solar orbit, these differences would be small, and measuring

the angles would require good instruments. Robert Hooke made a

heroic attempt in the 1670s, but not until 1838 did better

instruments give scientists reliable ways of gauging the

distances.

Parallax is a valuable tool because astronomical sightings

are inherently limited. A celestial body's location can never

be more than relative or apparent. The

universe has no center, no boundary, no fixed reference

points, no universal positioning grid. Planets, stars, and

galaxies spin toward or away from one another in a vast cosmic

flux that astronomers call "stellar drift," a term echoed in Ithaca:

"the parallax or parallactic drift of socalled fixed

stars, in reality evermoving wanderers from immeasurably

remote eons to infinitely remote futures." We peek

into this complexity like people viewing a huge whirling dance

through a keyhole. Stars may have ceased to exist by the time

their light reaches our eyes. Constellations obtain their

shapes only from our spatial location, and in a few thousand

years those shapes will be utterly transformed.

Such indeterminacy can set the mind reeling, as Bloom's does

in Lestrygonians just after he decides that trying to

understand parallax is a waste of time: "Gasballs spinning

about, crossing each other, passing. Same old dingdong always.

Gas: then solid: then world:

then cold: then dead

shell drifting around, frozen rock, like that

pineapple rock." Even observations here on earth enjoy no real

immunity from relativity. Until 19th century railroads created

a need for temporal uniformity, Greenwich and Dunsink time

differed not only from one another but from that of most other

English and Irish localities. Spatial relations too are

relative: the driver of a pickup truck sees a tree first on

the right flank of a mountain, and then on its left flank, but

the tree stands in no such relation to the hill. Its apparent

location is determined by the location of the motorist.

Joyce had no use for mathematical computation of distances,

but he found almost endless literary analogues for parallax

itself—the different views of an object obtained from

different positions. Ulysses extends the idea from

optics into the mental realm by a kind of implied analogy:

just as eyes take in the shifting spatial relationships of the

universe from different locations, yielding different views,

objects of thought take on different appearances according to

the angle from which they are viewed. One's subject-position,

which varies from individual to individual and even from

moment to moment in a single consciousness, affects what one

sees.

In Lestrygonians food looks different to Bloom

depending on whether he is in Burton's slovenly restaurant or

Davy Byrne's pristine pub.

Lemon sole seems elegant in a fancy hotel, and "Still it's

the same fish perhaps old Micky Hanlon of Moore street ripped

the guts out of making money hand over fist finger in fishes'

gills can't write his name on a cheque." Bloom

characteristically flops back and forth in this way, seeing

things first from one vantage point and then from another. It

marks him as a practitioner of parallax. In Hades he

listens to Simon Dedalus fulminating about Buck Mulligan and

thinks, "Noisy selfwilled man. Full of his son. He is

right. Something to hand on." Between the second

sentence and the third, Bloom shifts from the perspective of

an outsider who is barely

tolerated by men like Simon to the empathic view of a

father who has lost a son. From this angle, Simon's angry

pride appears very different.

In Cyclops, the Homeric parallel turns the denizens

of Barney Kiernan's pub into one-eyed

troglodytes who scorn binocular vision: Alf Landon says

of "Poor old sir Frederick"

Falconer that "you can cod him up to the two eyes."

(According to the OED, "up to the eyes" means "to the

limit." Alf adds the number.) In this monocular environment

Bloom's tendency to see things from multiple angles invites

ridicule. A discussion of reviving manly native Irish sports

prompts him to observe that strenuous exercise can be bad for

someone with a bad heart, which excites the narrator's

contempt: "I declare to my antimacassar if you took up

a straw from the bloody floor and if you said to

Bloom: Look at, Bloom. Do you see that straw?

That's a straw. Declare to my aunt he'd talk about it

for an hour so he would and talk steady." But a

straw is not just a straw. To a famished horse it is one

thing, to a phlegmy drinker another, to the man who

sweeps the floor still

another. Bloom's inclination to look at things from different

points of view identifies him as a complex life form, one with

stereoscopic depth of understanding.

Molly performs the same perpetual adjustments, regularly

using "still" and "but" locutions like those of her husband.

At the beginning of her chapter she criticizes Bloom for

pandering to old Mrs. Riordan

in hopes of getting an inheritance from her, but then thinks,

"still I like that in him polite to old women

like that and waiters and beggars too." Such flip-flops occur

throughout Penelope, especially in Molly's attitudes

toward her husband. They are contained in her endless

repetitions of the word Yes,

which open the chapter in a spirit of suspicious skepticism

and close it with joyful affirmation. Stephen too practices

parallax: his insistence that Haines be evicted from the tower

dissipates when Mulligan proposes giving him a violent "ragging," and his fantasy of

blowing an insolent doorman to bits with a shotgun flips over

into a recuperative fantasy of reconstituting

the bloody bits into a person. As he thinks later in Proteus,

"Ah, see now! Falls back suddenly, frozen in stereoscope. Click does the

trick."

Ulysses offers countless instances of intersubjective

parallax—different individuals' dissimilar views of the same

object. Molly and Bloom are always correcting each other in

this way. So too, from a greater distance, are Bloom and

Stephen. Joyce makes one such discrepancy particularly

suggestive of parallax by having the two men view the same

celestial object from slightly different angles. In Telemachus

Stephen sees a cloud begin

to cover the sun from Sandycove, at nearly the same time

(but not quite) that Bloom sees it from north Dublin. The

swallowing of the sun provokes dark thoughts of divine

judgment and personal despair in both men, but in slightly

different ways: Stephen thinks of his mother's ghoulish

visitation while Bloom thinks about Sodom and Gomorrha, the

Dead Sea, and sterility. In Ithaca, Stephen attributes

the crisis he experienced in the brothel, precipitated by his

mother's hallucinated reappearance, to the influence of this

"matutinal cloud," while in Oxen of the Sun Bloom's

thoughts of having no son give way to a nightmarish vision of

Palestine as a wasteland: "And on the highway of the clouds

they come, muttering thunder of rebellion, the ghosts of

beasts. Huuh! Hark! Huuh! Parallax stalks behind and goads

them."

Parallax also describes the bewildering variety of

perspectives on the book's actions taken by its many modes of

narrative presentation. From the first page, traditional

third-person objective narration veers into the subjective

orbits of certain characters. At times, notably in the third

and last chapters, interior monologue swamps exterior

narration, leaving the reader at the mercy of a character's

shifting thoughts, uncertain of what exactly may be happening

in the world at large. But objective narration too proves

shifty. In an unending series of experimental presentations of

the action—newspaper headlines, stage directions, parodic

styles, catechistic questions and answers—the novel makes its

readers jump from one viewpoint to another. It is filled with

instants when new perspectives pop into view: the moment when

free indirect style evocative of Gerty's thoughts suddenly

gives way to interior monologue conveying Bloom's, the moment

when a first-person narrator suddenly declares his existence in a

third-person book, the moment when people in the library

suddenly become dramatic characters in a script. In Wandering

Rocks parallax returns to its unmetaphorical, purely

visual roots, with sudden filmlike cuts from one scene to

another.

In The Book As World (1976), Marilyn French observed

that because of such constantly shifting views Parallax

"could have served as a title for this novel" (106). She did

not think, however, that the polymorphous subjectivity ruled

out the possibility of objective knowledge: "The fact that

various characters walk the same streets, see the same shops

or the same 'matutinal cloud,' or meet the same people confers

on these streets, shops, cloud, and people a solidity, a

reality. One way to test the reality of an object is to

compare one's perceptions with those of others . . . Joyce

builds into his book the solid substance of things. This is

all the more necessary since the modes of perceiving them are

so spaced out, so private and eccentric" (27).

In his critical study Ulysses (1987, first published

1980), Hugh Kenner too observed that the novel's pointillist

perspectivism has the effect of substantiating objective

reality: "Parallax makes possible stereoscopic vision: 'In

order to see that basket,' Stephen instructs Lynch in the Portrait,

'your mind first of all separates the basket from the rest of

the visible universe which is not the basket' (212), something

the mind can do more easily since two eyes have presented it

with separate versions of the basket's location. Two different

versions at least, that is Joyce's normal way; and the uncanny

sense of reality that grows in readers of Ulysses page

after page is fostered by the neatness with which versions of

the same event, versions different in wording and often in

constituent facts—separated, moreover, by tens or hundreds of

pages—reliably render one another substantial" (75).

Kenner selects more or less randomly the example of Bloom

seeing George Russell walking his bike on a route leading to

Kildare Street, and Russell then appearing in the National

Library in the next chapter: "This does much to assure us that

Bloom really did see Russell, a substantial Russell in motion

through Dublin's Newtonian space" (75). Bloom's recollection

of Robert Ball's book in Lestrygonians, supplemented

by its appearance on his bookshelf in Ithaca, prompts

Kenner to observe that "each speck in this book has somewhere

its complementary speck, in a cosmos we can trust" (76). The

narrative presentation of Dlugacz in Calypso, followed

by Bloom's memory of slightly different details about the

butcher later in the chapter, illustrates his claim that

"virtually every scene in Ulysses is narrated at least

twice, and by varying what he tells and emphasises Joyce

ensures that repetition shall not dilute but intensify" (76).

French's and Kenner's sensible critical responses to Joyce's

fiction cohere with the scientific concept, which does not

imply that celestial objects cannot be known, or that varied

observations will involve irreconcilable discrepancies.

Parallax implies only that stars will take on slightly

different appearances against different backgrounds. The

objects of human knowledge represented in Ulysses become

more fully known when seen from new perspectives—the more the

better.