When a hallucinated Josie Breen threatens to tell Bloom's

wife that she has found him in Monto ("I know somebody won't

like that. O just wait till I see Molly!"), he defends himself

by saying that Molly too would like to walk by the

whorehouses: "(Looks behind.) She often said she'd like

to visit. Slumming. The exotic, you see. Negro servants too in

livery if she had money. Othello black brute." As the

accompanying racist fantasy of being serviced by a black stud

makes clear, gazing on fallen women can be seen as an act of

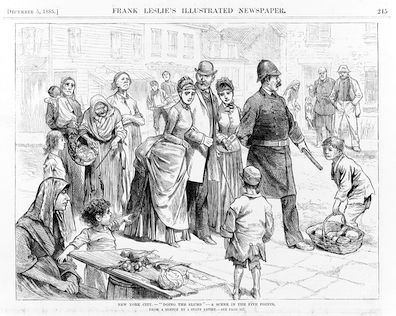

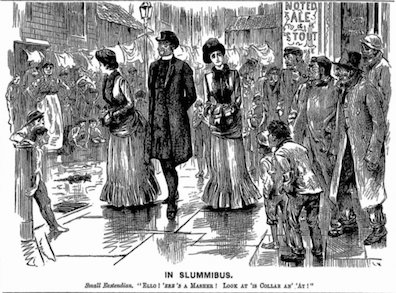

classist appropriation. For several decades people in London

and New York City had been "slumming"––touring ghettoes to see

poverty and depravity firsthand––although most of them

probably imagined their motives to be noble. It seems possible

that by 1904 Dublin was joining the trend.

Slum tourism, also

called poverty tourism or ghetto tourism, has attracted millions

of paying travelers in the 21st century, often hyping its

responsible practices and its contributions to the local economy

in places like the South African townships and Rio's favelas.

But according to Fabian Frenzel

et al in an article

titled "Slum Tourism: State of the Art,"

Tourism Review

International 18 (2015): 237-52, the phenomenon began

almost 150 years ago when upper-class Londoners began visiting

the slums of their city. The first documented uses of the word "

slumming"

come from that time. The

OED records an appearance in

1884: "I am not one of those who have taken to 'slumming' as an

amusement." And another in 1894: "Slumming had not become the

fashion at that time of day." The spread of this fashionable

amusement to New York City has been well documented.

The urge to see "how the other half lives" (a phrase popularized

by

Jacob

Riis in 1890) is an understandable human curiosity,

particularly in cities with such huge disparities of wealth as

existed in Joyce's Dublin, and perhaps the understanding gained

on slum tours produces a net increase in empathy. It would seem

that the earliest ones were conceived in philanthropic terms,

following hard upon the visits of reformers like the founder of

the Salvation Army,

William Booth. But voyeuristic

pleasure at viewing squalor up close, while having a nice home

to go back to, must always have played a part in people's

attraction to the slums. Joyce recognizes such motives in Molly,

or perhaps in Bloom's fantasies of what she likes.

Thanks to Vincent Van Wyk for calling my attention to slum

tourism.