Throughout the 19th

century London teemed with unfathomable numbers of unemployed or

underemployed people living in grinding, nearly inescapable

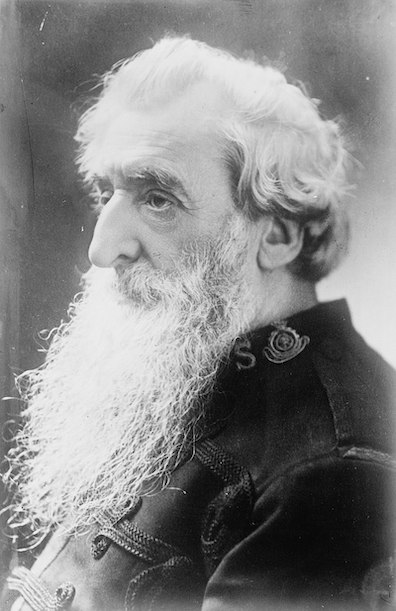

poverty. William Booth (1829-1912) began life as Charles Dickens

had, in a family slipping from prosperity into want. After

completing the apprenticeship into which his father placed him,

and moving to London to find work, he became an evangelist

preaching the Methodist doctrine: seek salvation by repenting

one's sins and practicing love for God and mankind. In 1865 he

and his wife Catherine founded a missionary and charitable

organization which in 1878 became known as the Salvation Army,

led by Booth as its "General." The Army brought three S's to the

poor: soup,

soap,

and salvation. In the 1880s it expanded from England into

Ireland, the United States, and Australia, and in 1890 Booth

produced a hard-hitting book,

In Darkest England, to

inform people about the sufferings and trials of the wretched

souls in their midst.

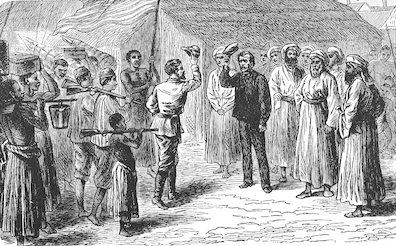

The title was provocative: it tweaked the English imperial

appetite for adventure narratives fed by books like Henry Morton

Stanley's

In Darkest Africa. Stanley was the

British-American journalist who in 1871 had famously found the

missing Scottish explorer David Livingstone ("Dr. Livingstone, I

presume?"). In 1890 he published

In Darkest Africa, the

story of his final exploration of the continent. Later in the

same year Booth published

In Darkest England; and the Way

Out, implying that the industrial revolution had made

England an uncivilized place, as full of hardship and

indifference as the darkest of continents. Bloom seems to be

aware of both books. In

Circe, recalling a cycling tour

that went amiss in the Irish village of Stepaside (west of

Killiney, a little beyond Dublin's southernmost suburbs), he

jokingly makes himself a Stanley-like explorer and reporter: "

I

who lost my way and contributed to the columns of the Irish

Cyclist the letter headed In darkest

Stepaside."

As for Booth's book, it is evoked by "

the submerged tenth,"

a phrase that Booth uses several times to argue that one in

ten English people are trapped in unconscionable poverty. The

second chapter, which takes the phrase as its title, is one of

several in which Booth quantifies his claims with hard numbers,

following Mayhew's practice of providing detailed numerical

estimates. The chapter also makes a more metaphorical call to

action that seems likely to have interested Joyce, though he

does not allude to it in

Ulysses: the "Cab Horse

Standard" for economic assistance. Booth observes that "every

Cab Horse in London has three things; a shelter for the night,

food for its stomach, and work allotted to it by which it can

earn its corn." Millions of London's human inhabitants, he

notes, are not afforded those minimal dignities or helped to

their feet when they collapse. Deploying Booth's phrase in a

chapter set in a cabman's shelter, Joyce may well have been

thinking of the Cab Horse Standard, but if so he did nothing to

call attention to it.

The word "

submerged," however, meshes intriguingly with

another element of the chapter's artifice.

Eumaeus is

filled with subtle, easily missed echoes of the 1912 Titanic

disaster, the great majority of them centered on evocations of

icebergs

or on the likenesses between the ship and

a

streetsweeper's horse. Might not "the submerged tenth"

figure in this design? More than 1,500 people died when the

great ship sank, many of them steerage passengers trapped behind

steel gates that sealed off their lower-level accommodations (C

through G decks) from those of the first- and second-class

passengers. These poor emigrants berthed below the waterline

might well be styled a submerged underclass, and when the ship

went down they were truly and permanently submerged.

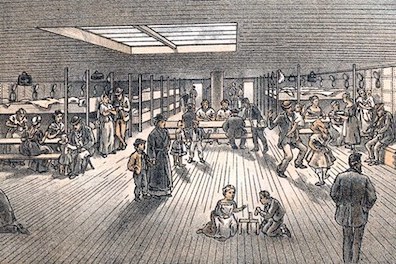

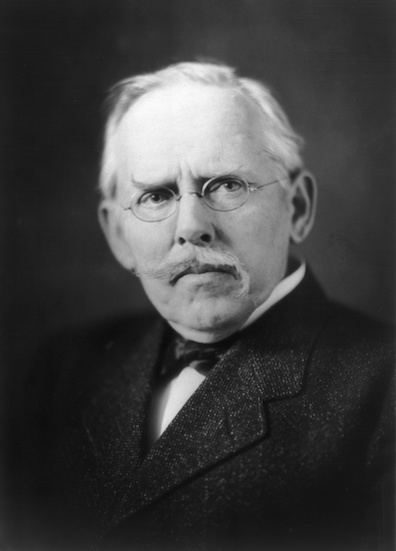

Bloom's words about Dublin's poor may also recall the work of

the Danish-American muckraking journalist Jacob Riis

(1849-1914). Like Booth, Riis experienced poverty as a young

man. He lived a hard life after emigrating to New York City,

working in many dead-end jobs and sleeping in horrific

flophouses

before beginning a successful climb in the newspaper business.

As a reporter he turned his attention to the squalor and crime

of the city's slums, and in 1887, when he learned of the

invention of flash photography, he began supplementing his

writing with vivid images. He also took up lecturing on the

theme "The Other Half: How It Lives and Dies in New York." In

1890 he published a book,

How the Other Half Lives. Like

Booth's

In Darkest England, the book sold well and

inspired hopes of social reform. In 1892 a sequel followed:

Children

of the Poor.

One reason to suppose that Riis may be part of the picture is

the strange observation that denizens of the underclass "

were

very much under the microscope lately." Studied like

bacteria? Not exactly, but if one strips away the obscuring mist

of cliché and inept characterization that pervades

Eumaeus,

it seems that this could refer to the visual medium of

photography through which Riis hammered home his message.

Another hint of his presence may be found in the enumeration of

groups: "

coalminers, divers, scavengers, etc." Booth's

book is filled with affecting accounts of unfortunate

individuals, and he often refers to their occupations, but he

does not display a penchant for group labels. Riis does,

following a different precedent from Mayhew's work. His pages

teem with cigarmakers, shoemakers, ragpickers, pedlars, beggars,

tramps, thieves, toughs, firebugs, working girls, wives,

mothers. He also happily traffics in ethnic stereotypes as he

describes the Italians, the Irish, Russian and Polish Jews,

Chinamen, Negroes, Bohemians, Germans. It is easy to imagine

Bloom applying such language to his experience of the Dublin

streets: he has passed two "scavengers" at the beginning of

Lotus

Eaters, in an urban wasteland much like those depicted in

Riis's photos. The first Riis photo displayed here and the first

shot of

Brady's Cottages show a striking resemblance.

(Incidentally, Mayhew took great interest in scavengers,

studying the "pure-finders" who collected dog droppings for use

in tanneries and the "mudlarks" who dug in the slimy banks of

the Thames for things that could be sold.)

Many thanks to Vincent Van Wyk for the Titanic observation, for

a suggestion that Riis may occupy space with Booth in Bloom's

thoughts, and for a follow-up reflection––explored below––that

the motives of both Riis and Bloom may not be entirely pure.

Riis did aspire to promote social change, and he worked with

Theodore Roosevelt and others to achieve it, but his detractors

saw him as sensationalizing the lives of the poor for personal

gain. The term "muckraking," coined by John Bunyan in

Pilgrim's

Progress and popularized in the Progressive Era that

started in the 1890s, carried some negative connotations.

(Roosevelt held that "the men with the muck rakes are often

indispensable to the well being of society; but only if they

know when to stop raking the muck.") The comparably unsavory

term "slumming" dates to the same era. In both London and New

York in the final decades of the 19th century, wealthy people

frequently visited blighted ghettoes as a form of

well-intentioned but sensationalistic tourism. Bloom thinks that

Molly wishes to make such a

tour of the red-light district.

Bloom is more charitable than most Dubliners, both

emotionally and in terms of his willingness to provide

financial assistance to the needy, but he is neither an

evangelist nor a friend of the underclass. By virtue of hard

work he, like his father, has become a prosperous middle-class

citizen with dreams of joining the property-owning elite, and

the neighborhoods he visits in Circe and Eumaeus

are foreign territory to him. Rather than feeling one with the

people in the cabman's shelter and aspiring to improve their

wretched condition, as Booth did, he sees them as materials

for Riis-like reportage. Just as a wrong turn in darkest

Stepaside encouraged him to become a Stanley-like reporter and

write a letter for a cycling magazine, the people in the

shelter present him with "a miniature cameo of the world we

live in," inspiring him to write something like "My

Experiences, let us say, in a Cabman's Shelter."

Such a piece of reportage might well do some good: since the

enactment of Union in 1800 Dublin had

become more and more blighted by poverty. But Joyce allows no

doubt about Bloom's primary motive for writing such a piece:

"Suppose he were to pen something out of the common groove (as

he fully intended doing) at the rate of one guinea per

column." These people, he reasons, have been very much

under the microscope in America lately. Perhaps an Irish

version would also sell....